Portrait of Robert Brown by Henry William Pickersgill, National Library of Australia,

Robert Brown, 1773-1858

Robert Brown [1] was a botanist who was on board the Lady Nelson. They reached Port Dalrymple on 1 January 1804 and sailed almost to the head of the Tamar River. Brown landed with William Collins, Thomas Clark and others but seems to have set off to explore on his own. In this account, Brown provides detailed information about the Aborigines he and others observed and met.

First encounter with ‘natives’

I landed in the forenoon & walked a little way inland to the first rising ground.

The Country in the neighbourhood of Lagoon beach was on fire.

On a rising ground about ¼ mile from the beach I observed eight native huts which appeard to have been long deserted: in every respect they resembled those described by Mr. Bass each of them were [sic] capable of containing two people only…

…Messrs. Humphrey, Collins &c [and company] who had walkd along the beach towards Outer Cover were met by a party of natives who seemd disposed to be troublesome & unfriendly & obligd them to return abreast of the Ship. [2]

On another day, Brown reported:

1804, 3rd [January] – At 7 AM got under weigh & ran up & anchored in Outer Cove completely land locked.

Natives about 20 came down to the beach but on our pulling towards them in the boat they went back into the woods and we saw no more of them to-day… [3]

4th [January]- A party of Natives appeard to have been watching us & follod us to the bottom of the hill where we had a friendly interview with four of them. We gave them biscuit which they did not however eat, and a few trifles & shewd them the use of a hatchet wch we could not spare them. They admired the effects of the hatchet & our skins wch we shewed them One of them gave me a young Pigeon wch appeard to have been speard in return for a piece of biscuit.

In their persons & colour they exactly resemble the inhabitants of N S Wales in stature they do not fall short of them & are rather better made especially having fuller calves to the legs their hair however is wooly tho I think no so much crispd nor of so full a black as the African negro.

The hair of the head was in most of them covered with ochre by wch some especially in the lads the weel was divided into small parcels The Faces of some were blackend & in the colouring matter a considerable proportion of minute mica was containd Their arms & thighs were tatood & in many was an archd line across the abdomen most of them had all their teeth perfect wch were in general white but not uncommonly white. The features of the boys were rather pleasing.

They speak quickly & their tones are not unpleasant I could not get them to understand that I wishes to have their names for the different parts of the body.

On top of the hill we sat down & in a few minutes 12 natives joind us at first they conducted themselves in a peaceable manner but by & bye they began to shew some symptoms of distrust as on my making some attempts to acquire a little of their language one of them smatched up a piece of wood & threatened to throw it at me at the same time raising his spear & two of them shapd their spears to throw at me I was then scarce five yeards from them the rest of the party being a few paces behind me.

I went cautiously back keeping my face to them they didn’t throw any spears but came close up to us We then found it necessary to fire a piece in the air at the report of wch they took to their heels but did not run far & continued while we leisurely walked down the hill on our return to the ship to follow us at scarce more than 30 yards distance.

As they seemd again inclind to close with us a piece charged with buck shot was fird at one they then took once more to their heels and afterwards followed at a greater distance We reachd the beach without further molestation It did not appear that the man fird at was hurt…[4]

…11th In the morning warped the vessel down abreast of Upper Island five native women came down to the shore abreast of the ship but on our putting off in the boat towards them retird into the woods… [5]

…15th Weighd & in the forenoon anchord between Green Island & Middle Rock.

The natives to the number of 30 or upwards including Women of whom there were several came down to the shore abreast of the ship & as appeared to us by their gestures wished us to land & renew our intercourse The women dancd to the song of the men who beat time very exactly with their waddies on their cloaks We were not sufficiently near to discern their movements in the dance On a red flag being displayed from the ship they frequently repeated Lappon Lilley Lappon Lilley.

The song was different from that of the Port Jackson natives Hoping to pick up some of their language & more accurately to contemplate their persons & manners a party pushd off from the shop in the boat by before they boat could land the women were sent away & the men came down on the shore shouting & throwing stones at us, two shots were fird over their heads upon which they ran off a little way & upon our landing they retird into the woods & did not return. [6]

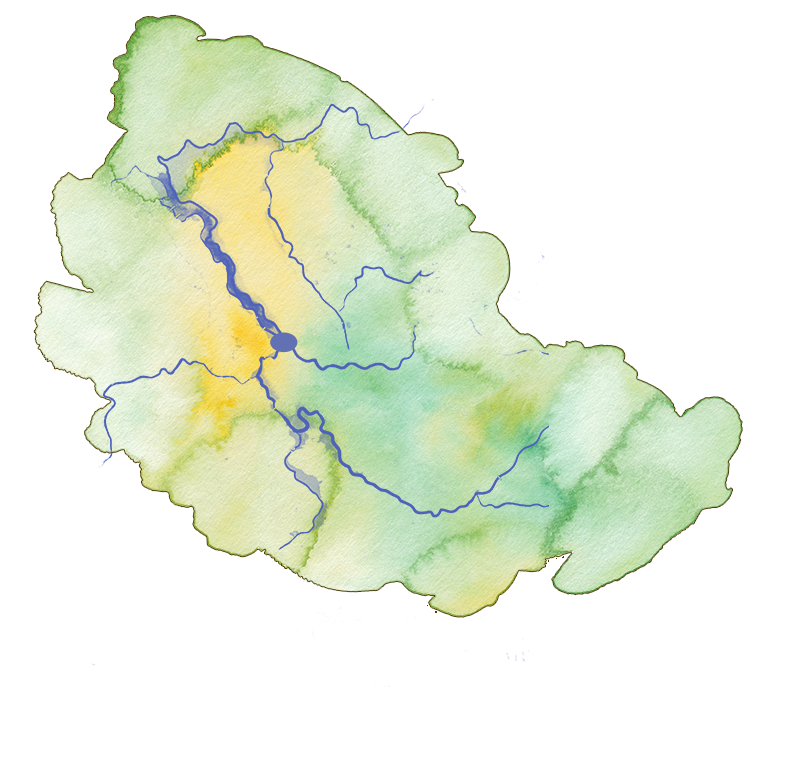

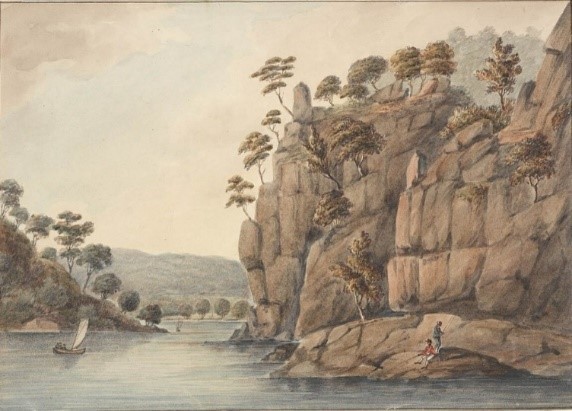

‘A view near Launceston’ by JW Lewin, 1809, copied from GP Harris, 1808.

William Collins, 1760?-1819

William Collins [7] was a naval officer, explorer and shipowner. He joined Lieutenant-Colonel William Paterson in 1804 to assist with the establishment of a settlement at Port Dalrymple. The expedition down the Tamar River, along the North and South Esk rivers to Cataract Gorge on 9 January 1804 was the highlight of his expedition.

Collins enthusiastically reported their first sighting of Cataract Gorge:

From Upper Island to the Head of the Main Body of the River the Country is alternately level and hilly, and has a delightful appearance. There are two Arms that lead from the Main head. I proceeded first up the one [North Esk], taking a South-East direction, as far as it is projected on the Chart, where the water is perfectly fresh and good. The River here is about Seventy or Eighty yards wide, and has a winding direction towards the junction of the two Ranges of Mountains to the E.S.E. it runs through a low Marshy Country which appears at times to be overflowed. The Soil on its banks is very good, and there is a great extent of it. This part is navigable for small Craft.

On my return I examined the Arm taking a S.W. direction [South Esk]; upon opening the entrance I observed a large fall of water over Rocks [Cataract Gorge], near a quarter of a Mile up a strait Gully, between perpendicular Rocks, about one hundred and fifty feet high; the beauty of the scene is probably not surpass’d in the World; this great Waterfall or Cataract is most likely one of the greatest sources of this beautiful River, every part of which abounds with Swans, Ducks, and other kinds of Wildfowl.

On the whole, I think the River Dalrymple [Tamar] possesses a number of local advantages requisite for a Settlement, and merits some attention. [8]

Lieutenant-Colonel William Paterson, ca. 1800, by William Owen, oil painting,

Lieutenant-Colonel William Paterson, 1755-1810

William Paterson [9] was a soldier, natural scientist. He served as Lieutenant-Governor of the northern settlement of Van Diemen’s Land from 1804 to 1809. Paterson was born in Scotland and served in the British army in India, Sydney and Norfolk Island.

In 1801 he argued with the notoriously quarrelsome John Macarthur and challenged him to a duel. Macarthur shot Paterson in the shoulder and was sent to England to face trial. Paterson’s health deteriorated over the years as a result of the injury.

In May 1804, orders were issued from London for the establishment of a new settlement at Port Dalrymple in Van Diemen’s Land, and Paterson was appointed as its administrator.

Paterson set sail from Sydney on 15 October 1804, with a contingent of soldiers and seventy-five convicts to establish the settlement. They set up camp at what they called ‘Outer Cove’ at Port Dalrymple, now York Cove in George Town. They then moved to a location on the west side of the Tamar River, which Paterson named York Town.

Paterson was instructed by Governor King to maintain a respectful relationship with Aboriginal People. But in spite of this order, the day after their arrival one of his guards killed an Aboriginal man and wounded another. The incident was recorded on 26 November 1804 in Paterson’s report to Governor King:

On the 12th [of November] a body of Natives, consisting of about Eighty in number, made their appearance within about One Hundred Yards from the Camp; from what we could judge they were headed by a Chief, as every thing given to them was delivered up to this Person; he received a looking-glass, two Handkerchiefs and a tomahawk; the former astonished them much; like a Monkey, when any of them looked into the Glass they put their hand behind to feel if there was any person there. The first Hut they came to they wanted to carry off every thing they saw, but when they were made to understand that we could not allow them they retired peacably. From this friendly interview I was in hopes we would have been well acquainted with them ere this, but unfortunately a large party (supposed to be the same) attacked the Guard of Marines, consisting of One Serjeant and two Privates, and insisted on taking their Tent and everything they Saw; they came to close quarters, seized the Serjeant and wanted to throw him over a Rock into the Sea; at last the guard was under the unpleasant alternative of defending themselves, and fired upon them, killed one and Wounded another; this unfortunate Circumstance I am fearful will be the cause of much mischief hereafter, and will prevent our excursions inland, except when well Armed. They threw several Spears and Stones but did not hurt any of our People. [10]

On another occasion, Paterson sent naval ensign Anderson on an excursion in search of suitable land for cultivation. In this instance, they ‘fell in with a party of Natives’ but had no communication with them. One of the soldiers estimated that there were about 200 Aboriginal People in the group. [11]

9th Dec’r [1804] This day saw about forty Natives, including Men, Women, and Children; they were very Shy at first; after endeavouring to convince them they we were friendly, one of them threw some Stones at a Soldier who I sent with a Handkerchief; observing he would not allow the Soldier to approach, I desired him to leave the handkerchief and a Tomahawk, which they afterwards picked up, much pleased with the present; as we [were] returning to where the Boat was, they followed us very close; being doubtful they might annoy us, in going off, with their Stones (which appear to be their principal Weapons), I ordered our Guard to remain on the bank until we got on board; after we put off the Soldiers found no difficulty in communicating with them; the Man who had the handkerchief gave the Soldier a Necklace of small Shells, which had a White Metal Button strung on it, and had the appearance of being worn for a length of time. Observing them so very friendly, I sent the Boat on Shore, with Messrs. Symons, Piper, and Mountgarrat, with some Fish, and also some Trinkets; but on their seeing the Boat they went into the Woods, which ended our Interview; but, from the Fires we have observed in that Neighbourhood since, it is probably they live chiefly in this Quarter. [12]

…The Melancholy loss among the Government Stock has occasioned me so much uneasiness that with the fatigue I was necessitated to undergo during the Winter it has greatly impaired my Health; but I have the pleasure to say that the Remainder are now in high Order, And I am now removing them from Point Rapid up to the Plains, and when that is accomplished I shall feel perfectly happy; my first Idea was to walk them by land, for which purpose I requested Mr. Riley to make himself acquainted with the Country from the Supply River to the Cataract, and furnished him with a Soldier and one of the Boat’s Crew and ordered the Boat to attend at different parts of the River to bring the party back.

The Man of the Boat’s Crew, I had ordered, was for Want of Shoes unable to proceed; but Mr. Riley and Private Richard Bent left the Supply on Sunday Morning the 1st instant, but after four hours’ walking without Meeting a drop of Water, altho’ they passed several places that had a Month Since 3 and 4 feet (which renders my intention of the Cattle going by Land impossible), they fell in with a body of about Fifty Natives, who immediately surrounded them and in the most decided Manner intimated they would not allow them to proceed on the course Mr. Riley was taking, viz. S.S.E., but with their Spears pointed to them another exclaiming “ Walla, Walla”; immediately on seeing them, Mr. Riley, in accordance with my wishes, if possible, to preserve Amity with these Savages, left the Guard and went unarmed to them when a mutual interchange of Notice took Place, in which they did not seem inimically disposed unless a desire to possess his Crevat [neck kerchief] and Clothes could be construed into this; but, however, during the elapse of time, Some of their party had fired the Hills entirely round them, and they were gradually drawing Mr. R. [Riley] and Bent to a thick Jungle; but, perceiving his Resolution not to enter it, they apparently in the most friendly Manner left him to his Route and to follow their own; but to further evince that nothing but Treachery is to be expected from these people, they unperceived sent more of their Numbers round a hill to intercept them, And at the Moment they were crossing a deep Gully surrounded with high Brush, Bent received a Spear fast in the Small of his Back, and in the instant Mr. Riley was drawing it he also received another fixed in his Hip; But Bent by this fortunately gaining a rise sufficiently to enable him to fire, with a general Shout they disappeared; but had either of them fell at the time, they would unquestionably have been Speared to Death.

After the Accident, they had about fifteen Miles to walk to reach the Boat, which they luckily had just strength to accomplish, Both of the Wounds were deep, But Mr. Riley is almost entirely recovered and Bent is now daily getting better, And I trust no bad Consequences will ensue to either. [13]

Dear Governor, Yorkton, 11th December, 1805.

….In my Public Letter I have stated the mode I have pursued in removing the remains of the Cattle, and anxious to know how they were getting on I was benighted in the Wherry, with a Gale blowing right up the River. This brought on a severe inflamation in my Eyes, but more particularly my best Eye, that I could not bear the light for some days. When I mention the Cattle, they have given me much uneasiness indeed, but I hope that those times are past, and I comfort myself with the idea that my troubles on that head are nearly at an end.

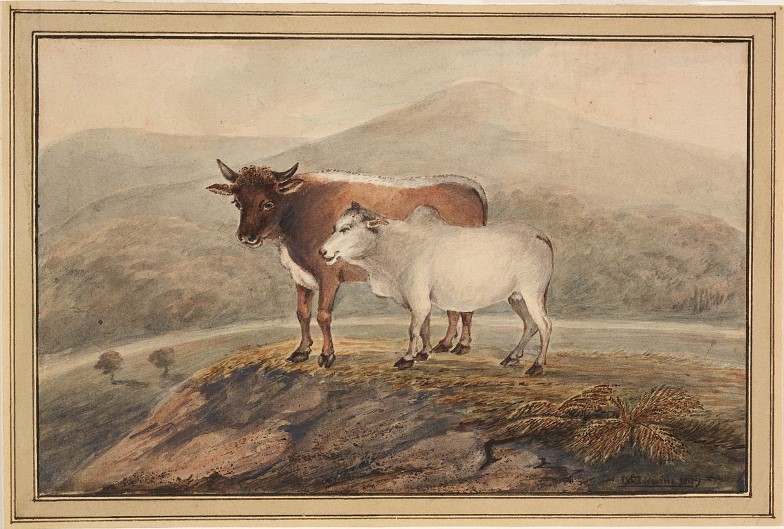

The intention I had of sending them by land, you will observe, was frustrated by the unfortunate circumstance which happened to Mr. Riley and the Party. Bent, the Soldier, was the person with him whose wound was dangerous, but he is now better. Mr. R. has not been well ever since. I rather think the Spear has penetrated very close to the Spine. In consequence of this disaster, as I was fearful the Water would not continue long at Point Rapid, I determined, tho’ reluctantly, to engage Mr. Mountgarret’s boat to transport them by Water, as stated; and as everyone has his price, I have promised him one of the Bengal Cows, when they are delivered safe at Brownrigg’s Plains, which I hope will meet with your approbation. I shall state this in my next Public Letter, assigning my reasons for having done so, when the Cattle, I hope, will be all safe landed.

A Bengali cow (front) and her English cross calf (rear) near the Cataract, Port Dalrymple’, by JW Lewin 1809 (Mitchell Library, SLNSW, a1313024)

Paterson and his party encountered many difficulties at York Town, including a lack of supplies, and the deterioration of Paterson’s physical health. However, he had a keen eye for the potential of the natural resources of the island. He imagined that the new settlement, with its iron reserves, could serve as a productive penal colony using convict labour, ‘by working them in irons, as they do in mines around the world.’

After a harsh winter in 1805 that contributed to the death of over half the herd of Bengal Cattle, Paterson decided to move them to what is now the Launceston area. You can find the details about this in the above correspondence from Paterson to Governor King.

Notes and references

[1] See N. T. Burbidge, ‘Brown, Robert (1773–1858)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/brown-robert-1835/text2113.

[2] Brown in Macknight, C.C. 1998. Low Head to Launceston: the earliest reports of Port Dalrymple and the Tamar, p. 70.

[3] Brown in Low Head to Launceston, pp. 70-71.

[4] Brown in Low Head to Launceston, pp. 71-2.

[5] Brown in Low Head to Launceston, pp. 75.

[6] Brown in Low Head to Launceston, pp. 75-6.

[7] See ‘Collins, William (1760–1819)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/collins-william-1913/text2271, published first in hardcopy 1966. Note: Williams Collins was not related to David Collins, the first Lieutenant-Governor of Van Diemen’s Land.

[8] William Collins in Low Head to Launceston, p. 67.

[9] See David S. Macmillan, ‘Paterson, William (1755–1810)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/paterson-william-2541/text3455.

[10] William Paterson in Low Head to Launceston, p. 82.

[11] William Paterson in Low Head to Launceston, pp. 85-6.

[12] William Paterson in Low Head to Launceston, pp. 102-3.

[13] Watson, F. & Chapman, P. (1914). Historical records of Australia, page 651.