After the Black War, when most of the remaining Tasmanian Aboriginal People had been exiled to Wybalenna on Flinders Island with George Augustus Robinson, there were reports of some Aboriginal People still living on the main island.

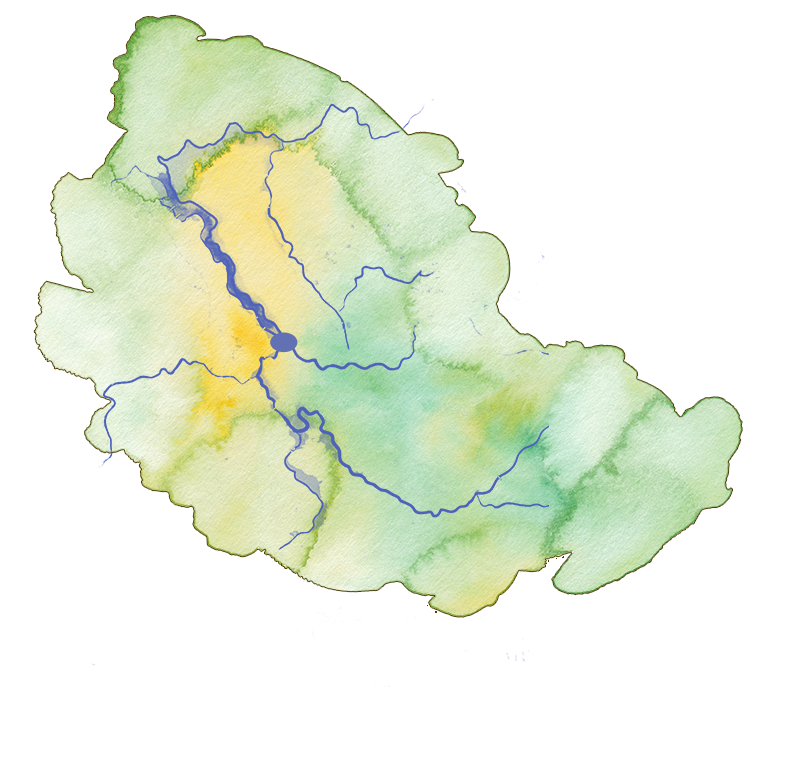

The following two accounts record the presence of a few Aboriginal People in the Tamar/Kanamaluka area in the 1830s and 1840s.

Weep in Silence. Edited by N.J.B. Plomley. Appendix I: B, Blubber Head Press, Hobart, 1987, page 847

JOSEPH TAMAR

In 1834 or 1835 Elizabeth Ramsdale adopted a little black boy found in the bush on the banks of the Tamar River by her son (CSO8/116/2438). She had him baptised Thomas Harlin Ramsdale (evidently the Thomas Harman, native name unknown, who was baptised by J.A. Manton, the Wesleyan minister and a notice of which appears in the baptismal register of St John’s Church, Launceston, certificate number 804 of 11 January 1835).

The child, who was then about five years old, was admitted to the Orphan School at Hobart Town on 28 June 1836, where he was known as Tamar Joe. Later (not determined) the boy was sent to Flinders Island.

In July 1841 Joseph Tamar, then supposed to be eight to nine years old, was sent to live with Captain Smith, master of the buoy-boat on the Tamar River, but it seems that the boy was not happy there and wished to go back to live with Mrs Ramsdale. No further information has been found.

_____________________________________

Button, H. 1993. Flotsam and Jetsam, A. W. Birchall & Sons, J. Walch & Sons, and Simpkin, Marshall & Co. 1909. Facsimile reprint. Regal Press, p.177-178

A small remnant had taken refuge in the remote and then inaccessible wilds of the north-west extremity of the island. For several years after, there were frequent rumours of blacks and smoke from their fires having been seen and their peculiar cry heard, with other indications of their presence. In most instances it is probable that these rumours were the creations of imagination, but there was some foundation for them.

In December 1842, a small party, ‘positively the last’, was captured at Woolnorth by a sealer whose boat they had previously robbed; they were sent to Circular Head, whence they were shipped to Launceston, and lodged in the Gaol until an opportunity occurred for transporting them to Flinders Island to join their compatriots.

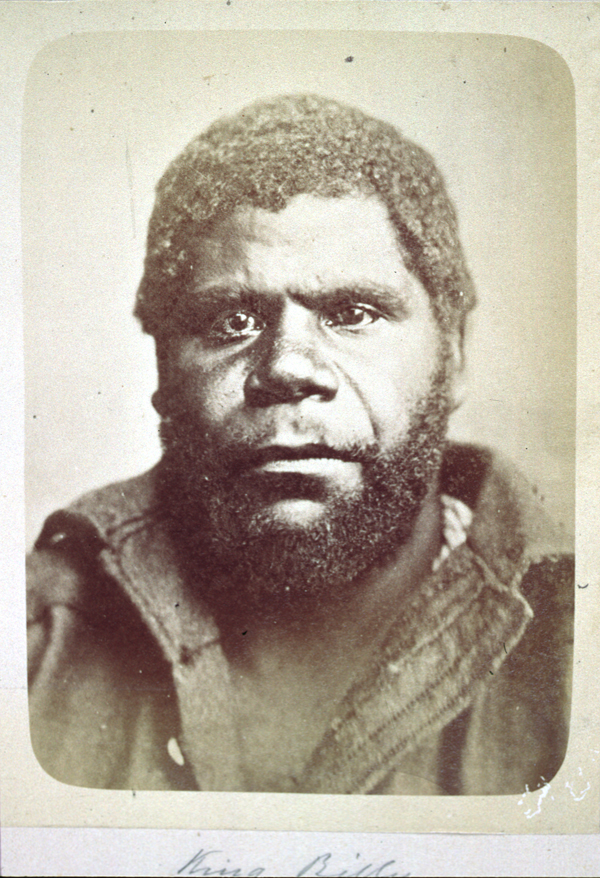

Photo of William Lanne as an adult

The party consisted of a single family of seven persons: the parents, about fifty years of age; and five sons ranging from thirty to infancy. I saw this melancholy remnant of a doomed race — the last of our Mohicans! [1]

Passing along Paterson Street one morning I met the little group on its way to the Wharf, where a craft was waiting to convey them to Flinders Island. My friend Mr. Monds has recently told me that he saw these blacks frequently whilst they were in Launceston, and that many years afterwards he read a statement in one of the local newspapers to the effect that one of the group was the identical King Billy [William Lanne] who is mentioned a little later, though I do not remember having heard it before, and Dr. Milligan does not mention it. [2]

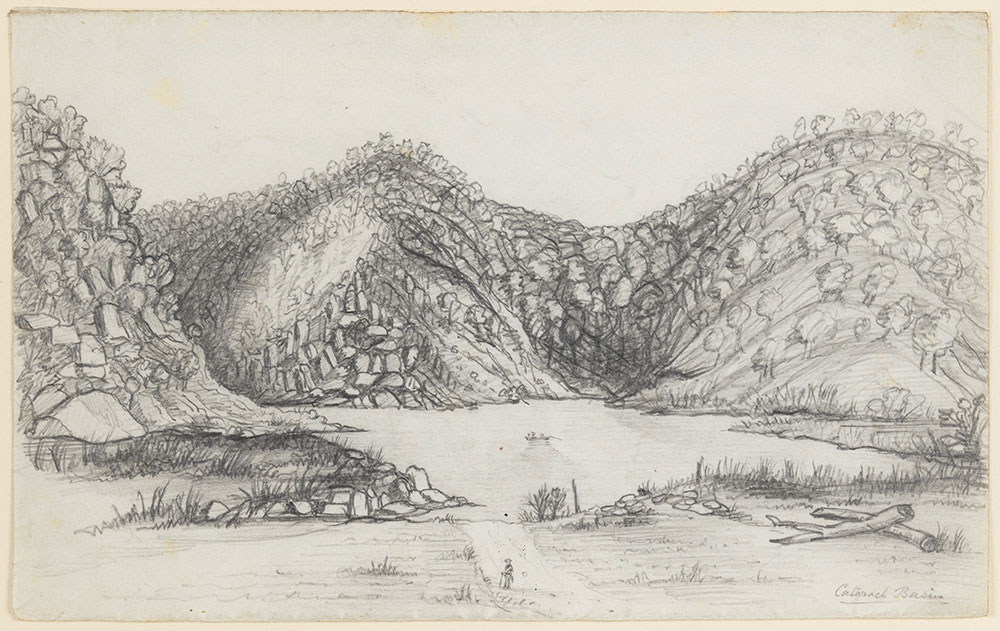

Sketch of Cataract Basin, by John William Hardwick, 1826-1891, SLNSW.

Leaping with delight at the Gorge

Reverend John West was an Anglican minister who arrived in Van Diemen’s Land in 1838. West founded the Launceston Aboriginal Benevolent Society and established a school for Aboriginal children. He was an outspoken critic of the transportation system, which he saw as a corrupt and inhumane practice that perpetuated crime and poverty in the colony and he played a significant role in the campaign to end the transportation of convicts. West was a prolific writer and authored important books and pamphlets on colonial life, social issues, and religion, including A History of Tasmania in 2 volumes in 1852.

This account of an Aboriginal man and young boy visiting Cataract Gorge was said to have taken place in 1847, when the people who had survived at Wybalenna on Flinders Island were transferred back the main island to live at Oyster Cove, the former convict government settlement south of Hobart. West wrote this account of this event for his book which was published in 1852.

A chief accompanied the commandant to Launceston in 1847. At his own earnest request, he was taken to see the Cataract Basin of the South Esk, a river which foams and dashes through a narrow channel of precipitous rocks, until a wider space affords it tranquillity. It was a station of his people… his excitement was intense: he leaped from rock to rock, with the gestures and exclamations of delight. So powerful were his emotions, that the lad with him became alarmed, lest the associations of the scene should destroy the discipline of twelve years exile: but the woods were silent: he heard no voice save his own, and he returned pensively with his young companion. [3]

Notes and references

[1] This is a reference to the famous historical romance novel written by James Fenimore Cooper in 1826 called The Last of the Mohicans: A Narrative of 1757.

[2] Raabus, C. 2012. ‘King Billy’s lasting legacy for all Tasmanians’, ABC Local Radio. https://www.abc.net.au/local/audio/2011/02/15/3139548.htm

[3] John West. 1852 A History of Tasmania – Vol 2 Printed by Henry Dowling Launceston. (Facsimile copy Adelaide, Libraries Board of South Australia, 1966) p. 21.