Encounters with explorers

From the first day the British set foot in northern Van Diemen’s Land they had encounters – good and bad – with Aboriginal People.

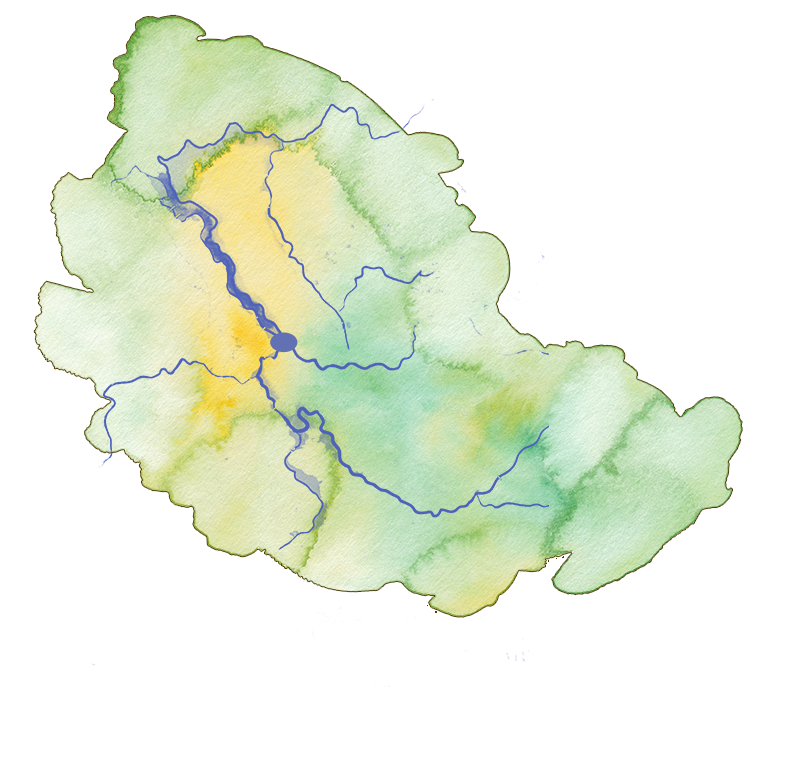

The Country of the Leterremairrener people was located on the lands where the three rivers meet. For thousands of generations, they lived in family groups of up to about 30 people. They spent winter moving along the east bank of the Kanamaluka/Tamar river to the north coast, living on shellfish, swans, and swan eggs.

In spring they began their journey inland toward the southeast to Ben Lomond where they spent the summer hunting kangaroo. At the end of January, they returned, following the river north to the coast for the mutton bird season. At various times the Leterremairrener people met with the other clans of the North Midlands Nation [1], the Panninher and Tyerrernotepanner peoples, to exchange shell necklaces for ochre and arrange marriages. [2]

Bass and Flinders’ voyage to Van Diemen’s Land, 1798

It had long been suspected by mariners that Van Diemen’s Land was separated from the mainland. George Bass and Matthew Flinders were sent by Governor Hunter to investigate. They left Sydney Cove in the Norfolk in October 1798 to prove the existence of a large body of water between the mainland and Van Diemen’s Land.

They sailed south along the NSW coast and arrived at the mouth of the Tamar River on 3 November. Flinders named it Port Dalrymple, after Alexander Dalrymple, the first hydrographer [3] for the British navy. [4]

For 12 days, Bass and Flinders explored Port Dalrymple and the northern part of the river to the Tamar estuary. They found fresh water, studied the flora and fauna and charted the river as far inland as Whirlpool Reach (near Batman Bridge).

After they left the Tamar river, they sailed along the west coast where Flinders named Table Cape, Circular Head, Hunter’s Island and Cape Grim. They then rounded the northwest tip and sailed down the southwest coast. They rounded the south coast, sailed into the Derwent River then headed up the east coast and back to Sydney Cove.

Replica of HMS Norfolk in Bass & Flinders Maritime Museum, George Town

Flinders recommended to Governor Hunter that the body of water between the mainland and Van Diemen’s Land be called after his friend, George Bass.

The following selection of primary sources were written independently by Bass and Flinders. They record their early encounters with the Leterremairrener clan of the North Midlands Nation in their Country, from Port Dalrymple to Launceston, from 1798 to 1806.

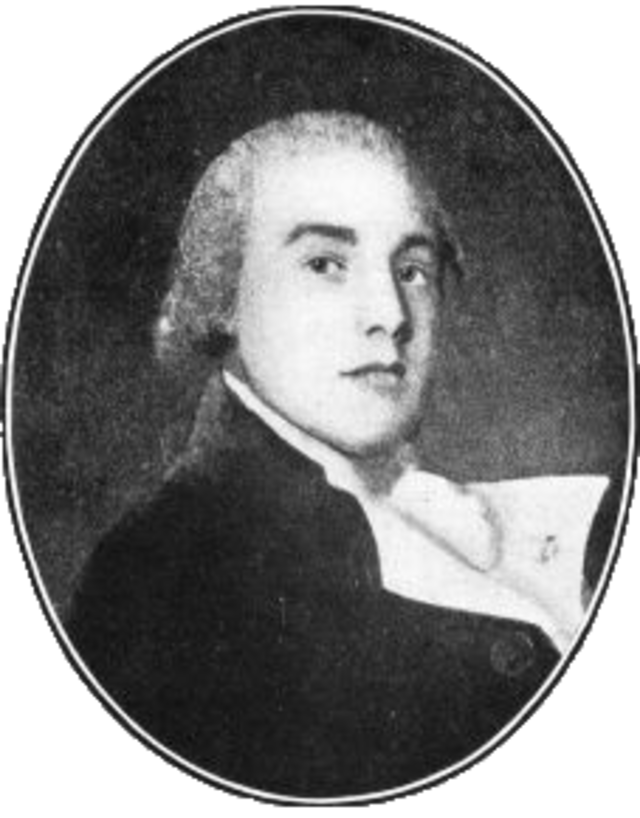

Captain Matthew Flinders, RN. 1774-1814, by Toussaint Antoine de Chazal de Chamerel, Wikimedia Commons

Matthew Flinders, 1774-1814

Flinders observed a series of islands off the Northern coast of Van Diemen’s Land – including Waterhouse Island and Swan Island – and concluded that Aborigines did not visit these islands because ‘they had no canoes upon this part of the coast’. What other conclusions did Flinders make about the lifeways and habits of Aboriginal People?

Flinders inferred from the attitude of seals and birds in rocky islets and Waterhouse Island, and the lack of marks made by humans on Swan Island, that Aboriginal People did not have watercraft that would enable them to reach the islands and therefore did not inhabit them. When he was on Waterhouse Island looking towards the Van Diemen’s Land mainland, he observed smoke rising and concluded that habitation was ‘most numerous between Port Dalrymple and Isle Waterhouse’.

The primary source extracts below are from Matthew Flinders’ [5] journal in which he describes features of the landscape, from Port Dalrymple along the Tamar River, and records his assumptions about the First Tasmanians in this area. [6]

Novr 6th During dinner time a native came down to the shore opposite to us, and employed or amused himself by setting fire to the grass in different Places and soon after we observed a smoke fire to the grass in the Middle Island. As I wanted some angles [measurements] from this place, Mr Bass and myself went there in our little boat but the natives had then left the Island, most probably at our approach; for soon after on looking around with a telescope, I saw three [natives] walking up from the dry flat, which at low water joins this Island to the main. They appeared to be a man a woman and a boy: the two former seemed to have something like a small cloak of skins wrapped around them.

_____________

The smokes which ascended from various part of this coast, gave us to understand that it was inhabited. These smokes were most numerous between Port Dalrymple and Isle Waterhouse. [7]

____________

If we may form any judgment from the traces of inhabitants that were found upon its shores, Port Dalrymple is peopled in almost the same proportion as the ports of New South Wales. Seven or eight huts were sometimes found standing together, like a little encampment; but the owners of them were always absent. Some natives once made fires abreast of where the sloop was lying; but as soon as the boat came near the shore, they ran off into the woods; and this was the nearest communication that their shyness would permit.

Concurring circumstances seem to point out, that the men of this place have no canoes. Middle Island [8] excepted, the isles in this port have no appearance of having been visited; and no tree was ever met with in the woods, whose bark had been taken off so as to be fit for making a canoe. The sum of our observations upon these people, and their mode of existing, was, that they have less ingenuity, and are more destitute of comforts and conveniences, than even the inhabitants of New South Wales.

__________

Muscles [MUSSELS] are numerous upon the rocks that are overflowed by the tide; and the natives appear to get oysters by diving; the shells being found in many places.__________ The Islands in Port Dalrymple would be found very convenient to a vessel for landing sheep upon, or other livestock, during her stay. Green Island [9] is secure, but the grass upon it is neither very good or abundant. Middle Island is a beautiful place, containing about forty acres of good pasturage; but the natives sometimes cross over to it: at low water.

George Bass engraving, from Wikimedia Commons

The country is inhabited by men, and, if any judgment could be formed from the number of huts which they [the sailors] met, in about the same proportion as in New South Wales. Their extreme shyness prevented any communication. They never even got sight of them but once, and then at a great distance. They had made fires abreast of where the sloop [boat] was at anchor; but as soon as the boat approached the shore they ran off into the woods. Their huts, of which seven or eight were frequently found together like a little encampment, were constructed of bark torn in long stripes from some neighbouring tree, after being divided transversely at the bottom, in such breadths as they judge their strength would be able to disengage from its adherence to the wood, and the connecting bark on each side. It is then broken into convenient lengths, and placed, slopingwise, against the elbowing part of some dead branch that has fallen off from the distorted limbs of the gum tree; and a little grass is sometimes thrown over the top. But, after all their labour, they have not ingenuity sufficient to place the slips of bark in such a manner as to preclude the free admission of the rain. It is somewhat strange, that in the latitude of 41 degrees, want should not have sharpened their ideas to the invention of some more convenient habitation, especially since they have been left by nature without the confined dwelling of a hollow tree, or the more agreeable accommodation of hole under the rock.

The single utensil that was observed lying near their huts was a kind of basket made of long wiry grass, that grows along the shores of the river. The two ends of a large bunch of this grass are tied to the two ends of a smaller bunch; the large one is then spread out to form a handle. Their apparent use is, to bring shell fish from the mud banks where they are to be collected. The large heaps of mussel-shells that were found near each hut proclaimed the mud banks to be a principal source of food. The most scrupulous examination of their fire places discovered nothing, except a few bones of the opossum, a squirrel, and here and there those of a small kangaroo. No remains of fish were even seen.

The mode of taking the opossum seemed to be similar to that practised in New South Wales, except that it is probably they use a rope in ascending the tree; for once, at the foot of a notched tree, about eight feet of a two-inch rope made of grass was found with a knot in it, near which it appeared to have been broken.A canoe was never met with, and concurring circumstances shewed that this convenience was unknown here; nor was any tree ever observed to be barked in the manner requisite for this purpose; thought birds bred upon little islands to which access might be had in the smallest canoe. Those made of solid timber seemed to be wholly out of the question. The trees bore no very favourable testimony to its excellence. They were rather the marks of a rough than of a shar-edged tool, and seemed more beaten than cut, which was not the case with the marks left by the mo-go, or stone hatchet, of New South Wales.

Hence, from the little that has been seen of the condition of our own species in this place, it appears to be much inferior in some essential points of convenience to that of the despised inhabitants of the continent. How miserable a being would the latter be, his canoe taken from him, his stone hatchet blunted, his hut pervious to the smallest shower of rain, and few or no excavations in the rocks to fly to! But happiness, like very thing else, exists only by comparison with the state above and the stage below our own.

Notes and references

[1] Lyndall Ryan calls them the North Midlands Nation; Tasmanian Aboriginal Elder and researcher, Aunty Patsy Cameron prefers to call them the Stoney Creek Nation.

[2] Ryan, L. 2012. Tasmanian Aborigines: A history since 1803. Allen & Unwin, pp. 29-31.

[3] A hydrographer studies the physical features of oceans, seas, coastal areas, and lakes and map the surface waters of the earth for navigation.

[4] In 1804, William Paterson established a settlement at Port Dalrymple. Governor Macquarie renamed it George Town in 1811 after King George III.

[5] See H. M. Cooper, ‘Flinders, Matthew (1774–1814)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/flinders-matthew-2050/text2541.

[6] Extracts from Observations on the Coasts of Van Diemen’s Land and its islands and on part of the coasts of New South Wales, By Matthew Flinders, Second Lieutenant of his Majesty’s ship Reliance, London, 1801. Project Gutenberg, http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks09/0900121.txt

[7] Waterhouse Island is located on the north west coast of Tasmania, between Bridport and Cape Portland.

[8] Middle Island is located opposite Beauty Point.

[9] Green Island was later known as Garden Island. It is no longer there because its rocks were used for construction.

[10] See Keith Macrae Bowden, ‘Bass, George (1771–1803)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/bass-george-1748/text1939, published first in hardcopy 1966.

[11] Bass’s journal was published in Lieutenant Colonel David Collins’ Account of the English colony in New South Wales, Vol. II. 1802. http://gutenberg.net.au/ebooks/e00011.html