Origins

Currently, the earliest verified scientific evidence of Aboriginal people on the land we now call Australia comes from Madjedbebe rock shelter in Arnhem Land and is dated to around 65,000 years ago. But it is important to understand that some Australian First Nations Peoples place no value on scientific dates or recordings of ‘firsts’ because according to their cultural traditions they ‘have always been here’, from The Dreaming.

The Dreaming is the term most commonly used to refer to Australian First Nations Peoples’ complex ways of knowing and being. But ‘The Dreaming’ is not a direct translation of this complex concept. Different First Nations languages contain different words for knowledge about creation, spirituality and beliefs, and time and place. Some of these terms are:

- jukurrpa or tjurkurrpa, (Pitjantjatjara People, north-western South Australia)

- altjeringa (Arrernte People, central Australia)

- ungud (Ngarinyin People, northern Western Australia)

- wongar (north-eastern Arnhem Land)

- bugari (Broome, northern Western Australia).[1]

We will use the term paywootta, the palawa kani [2] word used by Tasmanian Aboriginal Elder Jim Everett when he talks about ‘long time ago’ and Creation stories. [3]

paywootta

- is the beginning of time when Ancestors first created the world. These stories contain important lessons about people, Country, as well as rules for behaviour.

- is the origin of life; how animals, plants, hills, rocks, waterholes, and rivers were made by spiritual beings or ancestors. Ancestors could be creators of life or life itself; a river can be an ancestor and a creation snake.

- is the environment or places where Aboriginal Peoples lived in the past and live today in the present. It connects First Nations Australians to their spiritual ancestors through Country and forms their understanding of how the world was created.

- is about cultural things, such as art, objects (such as tools), knowledge, people, ancestors, spirituality and much more.

Another term used by some First Nations and non-Indigenous people today is ‘everywhen’.[4] The term was first used by the anthropologist W.E.H. Stanner in his 1956 essay when he tried to explain the complexities of the concept,

One cannot ‘fix’ The Dreaming in time: it was, and is, everywhen…a kind of narrative of things that once happened; a kind of charter of things that still happen; and a kind of logos or principle of order transcending everything significant…[5]

Creation

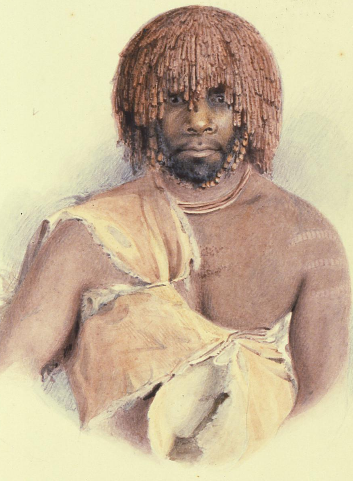

Creation stories give us an insight into how the First Tasmanians viewed the world, Some information was recorded by George Augustus Robinson in his journals, but his view was influenced by his own cultural perspective and his personal faith in Christianity. Here is the story of how the first Aboriginal people were created as told to Robinson by Wooreddy [6]:

Portrait of Woureddy (aka Woorady, Wurati, Woreddy, or Woorrady) by Thomas Bock, 1833 [8]

Woorrady said that moihernee [moinee] made natives… and that moihernee took him out of the ground and made parlevar [palawa = humans]; that when he was first made he had a tail and no joints in his legs, that he could not sit down and always stood erect, that droemerdeem saw him in this situation and came to him and cut off his tail, rubbed grease over the wound and cured it and made joints to his knees and told parlevar to sit down on the ground, that parlevar sat down and said it was nyerrae good, very good. [Woorady]said moihernee made all the rivers, that he cut the ground and made the rivers. [7]

Wooreddy’s story of Creation is summarised below by Professor Greg Lehman, Pro-Vice Chancellor Aboriginal Leadership, University of Tasmania

The kangaroo is a metaphor for Palawa identity in Tasmania. Aboriginal people knew the animal as Tarner, a creation spirit and ancestor of Parlevar, the ‘first man’. Through kinship obligations, the kangaroo bound Aboriginal people to the land and gave us a mythical identity as descendants of a creation spirit.

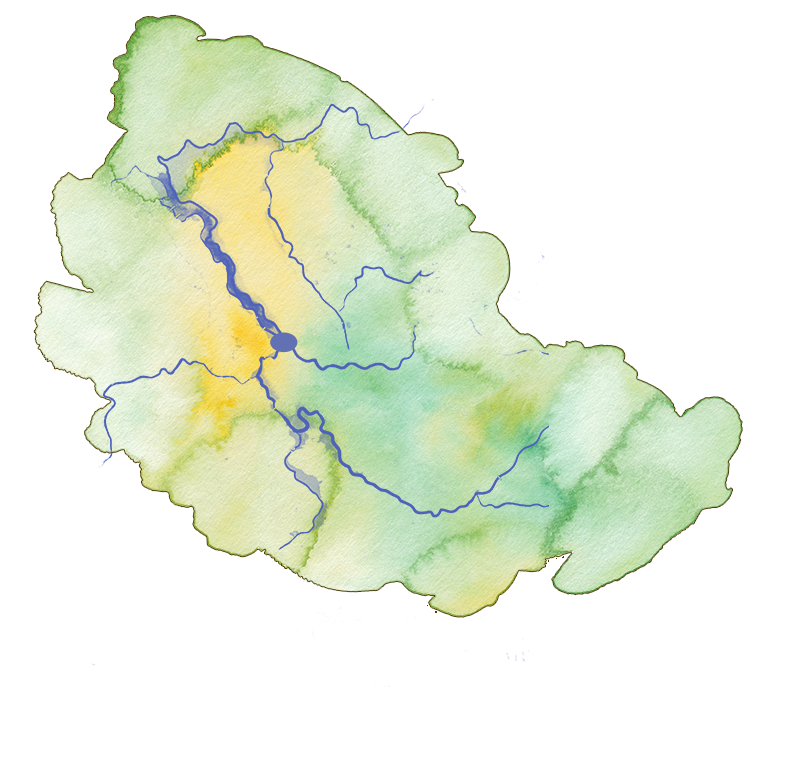

The notable Aboriginal ‘clever-man’ Woorady told how the kangaroo was an ancestor, transformed into Parlevar (Palawa) by the creation spirit Moinee. Before this transformation, Palawa had no knee joints and could not sit down. The spirit Droemerdeener broke his legs and cut off his tail, giving him a place to stay and live. As well as creating Parlevar, Moinee ‘cut the ground and made the rivers, cut the land and made the islands’. The kangaroo was also active in creation; Woorady said that the Tarner made the Lymeenne, lagoons. [9]

Here is another story about the creation of the stars:

A story which is common to almost all First Nations peoples is the legend of the Seven Sisters. The Seven Sisters are represented by the star constellation Pleiades. One legend has it that the sisters are pursued across the night sky by the stars that are the Orion constellation. Other stories follow similar themes, and they show a knowledge of constellations and their movements across the night sky.

In the case of the Seven Sisters, it was said that they had pouches from which ice crystals (frost) would be spread across the land

When the sisters were low in the night sky it was a sign cold nights with morning frosts would be happening. And if you woke up in the morning with a cold and wet nose you had been visited by one of the sisters. [10]

This story is about the creation of the Sun and Moon, as told by the Nuennone People of Bruny Island:

At the beginning of time, the Sun-man, Punywen (Parnuen) and the Moon-woman, Venna (Vena) travelled together across the sky, but Punywen was too fast for Venna and she fell behind. Venna rested her weary body on icebergs and as she did Punywen got further and further away from her. [11] To help her catch up Punywen illuminated more of her each night as encouragement to catch up with him. That story demonstrates that the Nuennone people recognised the Moon’s light as reflected sunlight.

Students can also watch the video of Aboriginal Elder Leigh Maynard telling the story of The Creation of Trowenna on YouTube https://youtu.be/g1XLsE9E24Y

You can find more Tasmanian Aboriginal Creation stories written for children in Rosemary Ransom’s Taraba – Tasmanian Aboriginal stories (1997). This book contains beautiful illustrations created by Tasmanian primary and secondary students. You can print the drawings on A3 size and use them when reading the stories to your students. They also make great classroom displays that will be useful additions to First Nations content.

Notes and references

[1] Australians Together: Language and Terminology Guide, v. 1.4, December 2021. https://australianstogether.org.au

[2] palawa kani means Tasmanian Aborigines speak’ and is the language of Tasmanian Aboriginal People today. For more information, see http://tacinc.com.au/programs/palawa-kani/

[3] Baird, A. (2008). Voices of Aboriginal Tasmania: ningenneh tunapry education guide. Tasmanian Museum and Art Gallery, (pdf), page 5. https://www.tmag.tas.gov.au/__data/assets/pdf_file/0004/66766/Voices_of_Aboriginal_Tasmania_ningenneh_tunapry_education_guide.pdf

[4] McGrath, A., Rademaker, L, Troy, J. (2023). everywhen: Australia and the language of deep history. NewSouth Publishing, University of New South Wales Press Ltd.

[5] Stanner, W.E.H. (1969). ‘The Dreaming (1953).’ In White Man Got No Dreaming: Essays 1938-1973, 67-105. ANU Press, 1979. https://openresearch-repository.anu.edu.au/handle/1885/114726. The 1986 Boyer Lectures. Australian Broadcasting Commission.

[6] Wooreddy was a renowned ‘clever man’, storyteller and warrior of the Nuenonne people from Bruny Island. He travelled around Tasmania with George Augustus Robinson, Truganini and others from 1830 to 1834. For more information about Wooreddy, see Baird, Voices of Aboriginal Tasmania: ningenneh tunapry education guide, page 5, https://www.tmag.tas.gov.au

[7] Plomley, N.J.B. (ed.) (2008). Friendly Mission: the Tasmanian journals and papers of George Augustus Robinson, 1829-1834, 2nd edition, pages 405-406.

[8] Portrait of Wooreddy by Thomas Bock, 1833, British Museum https://www.britishmuseum.org/collection/object/E_Oc2006-Drg-55

[9] Lehman, G., ‘The Palawa Voice’, Companion to Tasmanian History, https://www.utas.edu.au/tasmanian-companion/biogs/E000737b.htm

[10] Hamacher, D., with Elders and Knowledge Holders. (2022). The First Astronomers – How Indigenous Elders read the stars. Allen and Unwin.

[11] Academic researchers from universities in Queensland, Victoria and Tasmania have proposed that the melting ice indicates that this story goes back as far as the Late Pleistocene period, that is, before 11,700 years ago when Tasmania was separated from the mainland by the rising waters of Bass Strait.

[12] Trowenna is another name for lutruwita/Tasmania.

[13] Tasmanian Aboriginal Community with Liz Thompson (2012). The Creation of Trowenna: A story from the Neunone People of Bruny Island. Pearson Australia. See also Maynard, L. (2004). How the Tasmanian Tiger Got Its Stripes. Scholastic Press and the YouTube video at https://youtu.be/PEA7gkU4VaQ (NSW Film and Television Office in Association with Aboriginal Nations Pty Ltd). The story comes from the Nuenonne People of Bruny Island: Kannenner the Brave: The Tasmanian Tiger, as told by Leigh Maynard.