Water for life

Humans need water to survive. Our bodies are made up of around 60 per cent water, and water plays a vital role in regulating our body temperature, transporting nutrients and oxygen to cells, lubricating joints, and removing waste from the body. Access to clean drinking water is essential for human health and survival.

Before colonisation, access to clean, fresh water was easy for Tasmanian Aboriginal People. It was essential to their ability to survive the harsh, cold southern winters, especially during the Pleistocene Ice Ages. Most Aboriginal living sites (or middens) that have been identified in Tasmania are located besides streams, rivulets, or rivers. Aboriginal People needed to be close to and follow natural waterways because water was the key to their everyday survival.

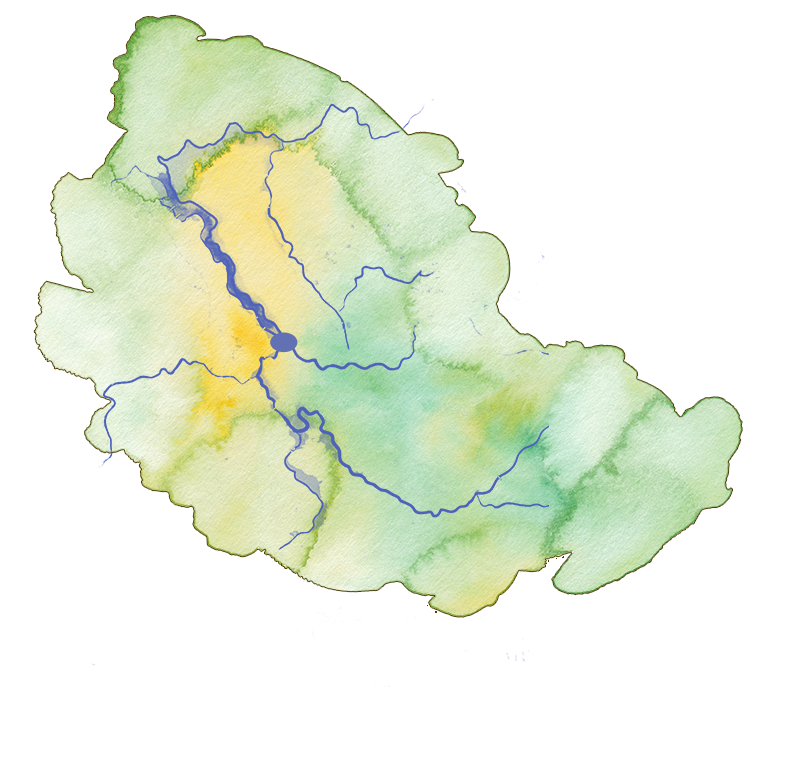

The catchment for the three rivers – the Tamar (Kanamaluka), North Esk (Lakekella) and South Esk (Pleepertoommerlar) [1] – were rich living areas for Tasmanian Aboriginal People for around 200 generations, which is estimated to span approximately 40,000 years.

To make a modern comparison, the smaller rivers of the catchment were like streets that Aboriginal People lived on and followed in their daily lives. Just as we follow streets when we want to go somewhere, Aboriginal People followed water sources because they provided the easiest and most obvious and means of travel through the landscape.

When it came time to travel out of their local area they followed their ‘streets’ (streams/rivulets/small rivers) to a larger water source (such as a larger river, such as the Meander) that would be the equivalent of a main road for us now. And to go somewhere significant maybe once or twice a year, they would follow that ‘main road’ river to a ‘highway’ river.

In northern Tasmania those ‘highway’ rivers were

- The South Esk River (which has three known Aboriginal names; Mangana Lienta (‘big freshwater on the plain’); Mooronnoe (‘big freshwater’); and Pleepertoommerlar (‘fast water’ and refers to the river flowing through the Cataract Gorge);

- The North Esk River (which was known as Lakekella (‘freshwater).

- The Tamar Estuary, (which has two known names; Kanamaluka (lower reaches) and Ponrabbel (upper reaches near Bass Strait).

Once Aboriginal People followed the ‘highway’ rivers to what is now Launceston, where all three rivers meet, they would make their way to higher ground. At high places like Trevallyn Reserve they would meet for gatherings of possibly up to 1000 people. There they would perform ceremonies of family reunions, singing, dancing, trade, and organise marriages. High places offered a strategic view of the landscape from where they could see who was approaching.

Shell of a freshwater mussel (photo: G. McLean)

Water for food

Waterways are abundant sources of various types of seafood and the South Esk River (Pleepertoommerlar), particularly through the lower reaches of the Cataract Gorge and First Basin, was once an abundant source of large, freshwater mussels. These mussels were a great source of protein which was integral to the diet of Aboriginal People. A shell was also a valuable multi-purpose tool and trade commodity. It could be used as a drinking implement, a bowl for mixing ochres, or a small spade for digging up root-based foods.

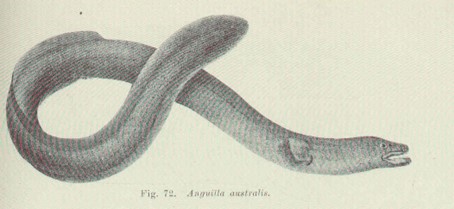

Short-finned eel (Anguilla australis). Wikimedia Commons.

Another valuable protein source found in freshwater streams and rivers was the Short-finned Eel, which is still abundant in the area today. Eels were most likely harvested using conical traps woven from plants such as River Reed, Sagg, Blue Flax Lily and White Flag Iris (also called Snake Lily by the Ancestors as its flowering signalled warm weather that would see snakes becoming prevalent). It is likely that Tasmanian Aboriginal People smoked, preserved, and traded eels in the same way as did Aboriginal People at Lake Condah (Budj Bim) in Victoria (refer to Eels and Seals section for more information).

Another freshwater food source would have been frogs which are rich in protein, especially the thighs which contain omega-3 fatty acids and vitamins. There are 11 known species of frog in Tasmania (there may have been more before colonisation) which can be found in all forms of freshwater, from small creeks, and streams to major rivers. [2]

Sketch of a Giant Freshwater crayfish (Astacopsis gouldi) by convict artist William Buelow Gould..

Freshwater crayfish would have been another rich food source. There are 37 species and the now protected Giant Freshwater Crayfish can weigh up to 6 kilograms. At Cataract Gorge there is a section of the South Esk River, just below First Basin that was known as Lobb’s Hole. It may have been given the name because it was a source of freshwater crayfish (called ‘lobster’ by some colonists). The land above Lobb’s Hole (now the Picnic Grounds) was once marshy wetland and an ideal place for the burrowing creatures to live. [3]

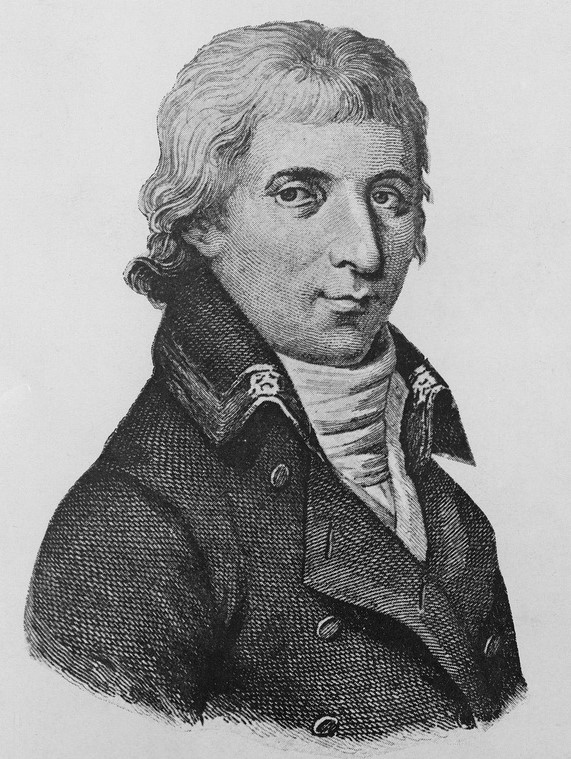

Portrait of French explorer, Nicolas Baudin, 1800 (Wikimedia Commons)

In 1802, French explorer, Nicolas Baudin (1854-1803) recorded how Aboriginal People in south-east Tasmania caught, cooked, and ate Saltwater Lobster. [4] Baudin described how they cooked the lobster by placing it directly on hot coals. He said that there was an abundance of oysters, abalone, and lobster and that, ‘Every day we caught more than the crew could eat’. [5] It is likely that Aboriginal People in the Tamar/Kanamaluka area used the same process to cook freshwater crayfish, whose flesh is sweet and delicious. [6]

Fresh water is integral for human survival, but we now take it for granted as it is delivered to us at the turn of a tap. For Aboriginal People, freshwater provided food and other resources, such as River Reed for weaving string, rope, and baskets. The creeks, rivulets and rivers were also ways for Aboriginal People to navigate the landscape of the Tamar/Kanamaluka system.

The availability of the many streams, rivulets and two major freshwater rivers is why the colonists eventually chose to settle in Launceston (see timeline). Launceston was the meeting place of rivers that deposited rich soil and made the soil rich and suitable for farming. We should also remember that this was an important reason why it was the meeting place of Aboriginal People for hundreds of generations. [7]

Notes and references

[1] Tasmanian Aboriginal language names used here for the rivers are European interpretations and as such the spellings are not definitive. The modern Tasmanian Aboriginal language of palawa kani may have different versions of the spellings.

[2] Tasmanian Parks & Wildlife Service, https://parks.tas.gov.au/discovery-and-learning/wildlife/reptiles-frogs

[3] This sketch of a Freshwater Crayfish was produced c.1832 as part of a 36-image still-life sketchbook while William Buelow Gould was a convict on Sarah Island, Macquarie Harbour Penal Station. The paintings were probably done for Dr William De Little. Source: Tasmanian Archive and Heritage Office Commons.

[4] You can read about Nicolas Baudin and his expedition to Van Diemen’s Land at Leslie R. Marchant and J. H. Reynolds, ‘Baudin, Nicolas Thomas (1754–1803)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/baudin-nicolas-thomas-1753/text1949

[5] Dyer, C.L. (2005). The French Explorers and the Aboriginal Australians, 1772-1839, University of Queensland Press, p. 65.

[6] Freshwater crayfish are listed as an endangered species and protected from being harvested. You need a license if you wish to catch crayfish recreationally.

[7] Thomas Scott. Sketches. 1822. Van Diemen’s Land’, 1822-1847, https://collection.sl.nsw.gov.au/record/nZNv867n/86awy8Kv3aWaJ.