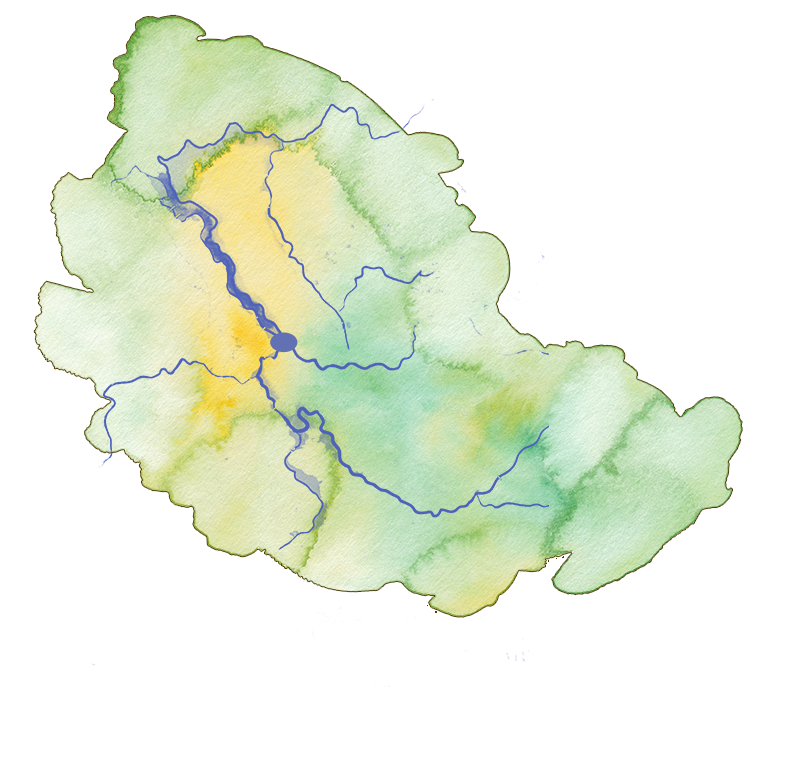

The Black War [1] was the violent conflict which took place between European colonists and Tasmanian Aboriginal People from about 1824 to 1832. There had been violence between both parties since first contact, with much of it as abuses by convicts, colonists, sealers, and shepherds against Tasmanian Aboriginal People.

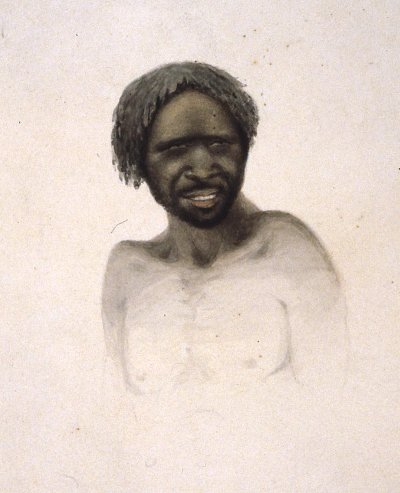

Watercolour drawing of Tongerlongerter, by Thomas Bock, 1832, British Museum

From 1820, the number of colonists increased and they expanded their farms into the traditional lands of the Oyster Bay, Big River and North Midlands nations. Aboriginal People were cut off from the lands where they hunted for food and gathered seasonally for ceremonies and trade.

Aboriginal People began to work together and fight back against the abductions, murders, dispossession, and destruction of culture that had begun with colonisation and escalated as more colonists and convicts arrived and took possession of their lands.

Leaders of Aboriginal resistance

Kikatapula was an Aboriginal resistance fighter from the Oyster Bay nation. Known by colonists as ‘Black Tom’ or ‘Black Tom Birch’, Kikatapula lived between two cultures; he had been abducted as a child and raised in the households of colonists, baptised as a Christian and was fluent in English. Kikatapula eventually reacted against the many abuses he and his people had suffered and by the mid-1820s ‘Black Tom and his force of natives’ became the most feared Aboriginal warriors in the colony. [2]

The Oyster Bay nation, led by Tongerlongeter, forged an alliance with the Big River Nation, led by Montpelliatta, and together they waged a terrifying, guerrilla-type war [3] against the colonists. [4] They were later joined by people from the North Midlands Nation, with Moleteheerlaggenner (also known as Kahnneher Largenner, and called ‘Eumarrah’ by the colonists), as their main leader.

Portrait of Moleteheerlaggenner (aka Eumarrah ),1832, British Museum

Lack of reporting in the north

Most of the reported incidents of violence occurred in the South, East Coast, and the Midlands; fewer incidents were reported in the Tamar region. This may have been partly due to the fact that Launceston did not have its own newspaper until 1829. Prior to 1829, encounters, casualties, or attacks in the north may not have been reported at all. If they were, they were reported in the Hobart press via ‘Launceston correspondents’. It is likely that many incidents escaped mention and lived on only in the memories of those concerned.

Reverend John West, 1809-1873, Wikimedia

Until 1829, printed media coverage of the Launceston area consisted of one publication, the short-lived Tasmanian and Port Dalrymple Advertiser, which only published twenty weekly issues from January to May 1825. Before the Launceston Advertiser and the Cornwall Press were operating in 1829, there were no newspapers in Launceston to record daily occurrences in the north. The concentration of newspapers in Hobart prior to this was a deliberate policy of Governor Arthur to destroy the business of Hobart newspaper proprietor and critic Andrew Bent, by removing the Launceston newspaper to Hobart in direct government subsidised competition to Bent. [5]

Founded by James Aikenhead, The Examiner was first published on 12 March 1842. The Reverend John West was instrumental in establishing the newspaper and was the first editorial writer. West also wrote The History of Tasmania, Volumes 1 & 2), which you can find in libraries and online.

George Arthur, Governor of Van Diemen’s Land,1824-1836 (Wikimedia Commons)

Violence in the north during the Black War

Below are several reports about the Black War in the north which are organised in chronological order. Note the tone and language of the reporters who use words like, ‘disgust, detestation, and horror’ and describe the Aborigines as ‘these horrid savage murderers’.

Gruesome details were included in order to make colonists fearful and angry: ‘…he was quite dead, having been speared through the lungs, and also in several parts of his body; on looking further, they found the body of Thomas Johnson, he was also lifeless, having no less than 11 spear-wounds in his back, and his neck dislocated by blows, supposed to be by the waddies of these sable [Black] destroyers.’

You will also notice that the reporting is very one-sided. Newspapers did not report details about the murder of Aboriginal People by colonists, bushrangers, convicts, and the military, and of course, accounts were not written by Aboriginal People themselves.

Although some people expressed some sympathy for Aboriginal people and recognised that they were acting in response to being dispossessed of their lands, cut off from their food supplies, kidnapped and murdered, many reports portrayed them as aggressors to justify Governor Arthur’s heavy handed military action and secrecy.

____________________________________

THE TASMANIAN. WEDNESDAY, January 12, 1825. Tasmanian and Port Dalrymple Advertiser, page 2.

In the course of last week about 200 of the aborigines made their appearance in the Town of Launceston, and immediate neighbourhood, encouraged no doubt by the accounts of the kindly reception, and civil treatment, which their sable brethren recently experienced on the other side of the Island. We certainly should have felt much gratification in recording, had we been able, that these poor wanderers of the woods, on their first approach towards civilization, had discovered in us, on this side of the Island, a disposition savouring more of humanity, if not of hospitality. What room have we left — we who are an enlightened people, and professing christianity — to express our disgust, detestation, and horror, on hearing a recital of the dark and nameless deeds of the untutored savage, who, rude as nature formed him, is left to prowl through the wilderness; while, at the same time, the very threshold of our polished doors are stained with spots of but a lighter hue. Even on their way hither these defenceless creatures (for they came unarmed) were wantonly and maliciously fired at by some of the settlers in the vicinity of Patterson’s Plains; and, as if that was not enough for ever to forbid them peeping out from beneath the shelter afforded them by nature, scarcely had they been in, and left Town again, before one of their women, in the immediate vicinity of it, was used in a manner, which, for brutality, beggars description. We are happy, however, in being able to state, that it is the firm determination of His Honour the LIEUTENANT GOVERNOR (who, fortunately for the ends of justice, was in Town at the time), to punish those wretches, whose minds must have been beneath that of the brute creation, with the utmost severity the law can inflict.

_________________________________

Colonial Times and Tasmanian Advertiser (Hobart), Friday 3 February 1826, Page 4.

Extract of a letter from one of our Launceston Correspondents;-

The bones of a man named Carpenter, servant to Mr Lawrence, supposed to have been killed by the Aborigines, were found last week, two waddies were found by the remains.

______________________________

Button, H. 1993. Flotsam and Jetsam, A. W. Birchall & Sons, J. Walch & Sons, and Simpkin, Marshall & Co. 1909. Facsimile reprint. Regal Press, page 174.

I have heard many harrowing tales of encounters with the blacks, of frightful atrocities perpetrated by them and on them, also of hair-breadth escapes from their vengeance, though for the most part they have been forgotten. One such incident, however, recurs to me which will illustrate the extreme peril to which the scattered settlers were exposed.

It occurred on the west bank of the Tamar, twelve or thirteen miles from Launceston. Mr. Beckford occupied a small farm just beyond Muddy Creek. One day, when alone, Mrs Beckford, who had been washing, was hanging out linen on a line in the garden, when she was startled by the report of a gun in close proximity. Her first thought was bushrangers! And she expected her home was to be laid under contribution; but the next minute the truth was explained.

An armed man came forward, who was indeed a bushranger, none less than the notorious [Matthew] Brady [6], but on this occasion he was a deliverer. His reputed haunt was not far off, a rocky eminence at the back of Rosevears, still known as ‘Brady’s Look-out’, which commands a view of the river and surrounding country for many miles.

At the time in question he was prowling around, in the vicinity of Beckford’s cottage, possibly contemplating a raid upon it, when he caught sight of a native with poised spear directed at Mrs. Beckford as she was engaged in her garden, all unconscious of the impending danger.

Brady’s shot killed the native, but it saved Mrs. Beckford, and she might be excused if, in grateful recognition of his opportune intervention, she replenished the outlaw’s stores without pressing him with inconvenient questions! To harbor or in any way to succour a bushranger was held to be a crime only one degree removed from that of the marauder himself. I knew Mr. and Mrs. Beckford very well, and had this story from their own lips something like sixty years ago. Mr. Beckford was then organist at St. John’s Church.

___________________________________

The Hobart Town Courier, Saturday 27 October 1827, page 2.

It is with much regret we learn that the black natives have killed another man, servant to Mr. Andrew Birrell, about ten miles below Launceston on the banks of the Tamar.

_____________________________

The Tasmanian (Hobart) Friday 21 December 1827, page 3.

(From our Launceston Correspondent)

December 17th 1827

The natives are still very troublesome;- one old man of the name of Rutter was brought into town, yesterday, who had been murdered by them, not more than 5 miles from the town; and others have been chased and speared by them near the settlement, this week. It is to be hoped all hands will rise against these horrid savage murderers.

“The Country Post”, The Hobart Town Courier, 15 November 1828.

Ben Lomond. -The black natives have again commenced their outrages in this district. About six weeks back they speared a shepherd belonging to Mr. Dark, in sight of that gentleman’s house. The man has been ever since in the General Hospital, Launceston. About a week after that they robbed Mr. Bonney’s stock hut of blankets, flour, sugar, &c. Three days after they pursued a shepherd of Mr. Massey’s; the same day they threw a spear at Mr. Sinclair’s shepherd; the spear passed over the man’s shoulder, and through a ewe about two rods before him, which the man was driving. The man escaped by running from them. Last Saturday, week they speared and beat with their waddies a man of Mr. Reed’s, near the same spot. Yesterday they attacked a servant of Mr. Sevior’s, whom they endeavoured to surround; the man saved his life by discharging his musket two or three times, and retreating every time until he got to his hut where other men were.

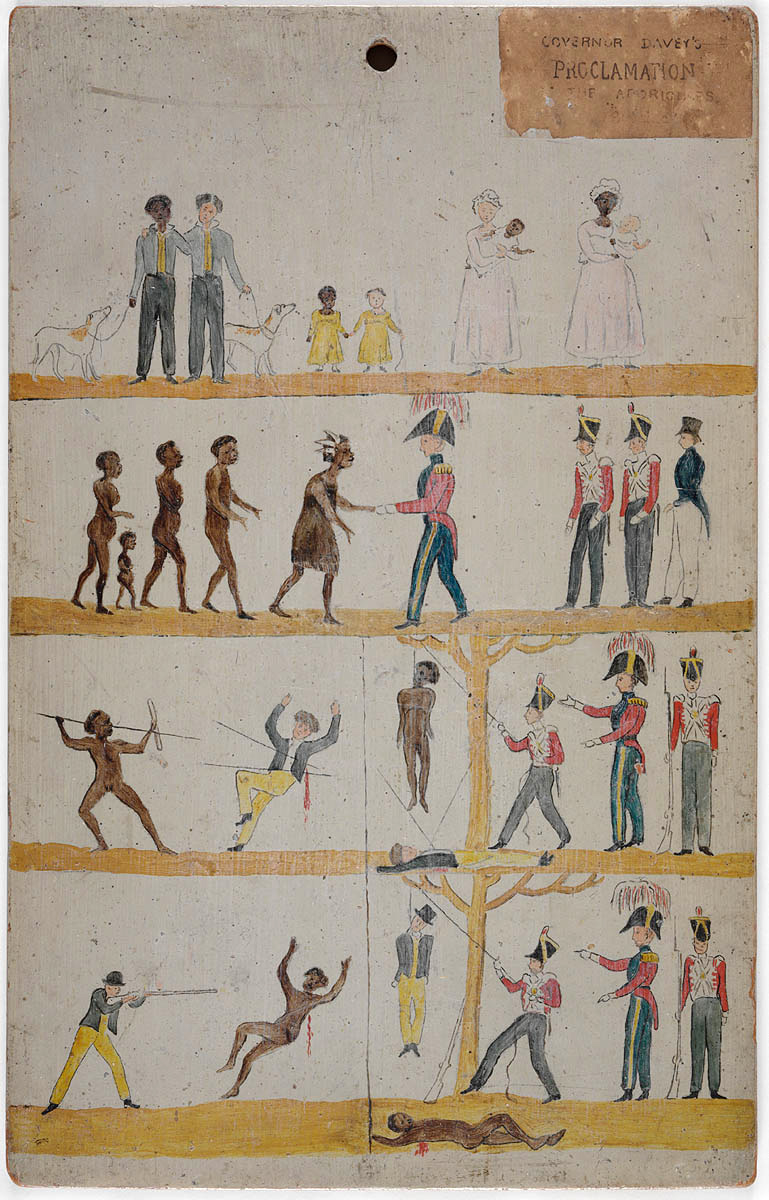

Governor Arthur’s ‘Proclamation Board to the Aborigines’, c. 1828-30. [7]

Friendly Mission. The Tasmanian Journals and Papers of George Augustus Robinson 1829-1834. Edited N.J.B. Plomley. Queen Victoria Museum and Art Gallery and Quintus Publishing, Hobart, Second Edition, 2008, page 546.

10 November 1831 (Journal Entry by George Augustus Robinson)

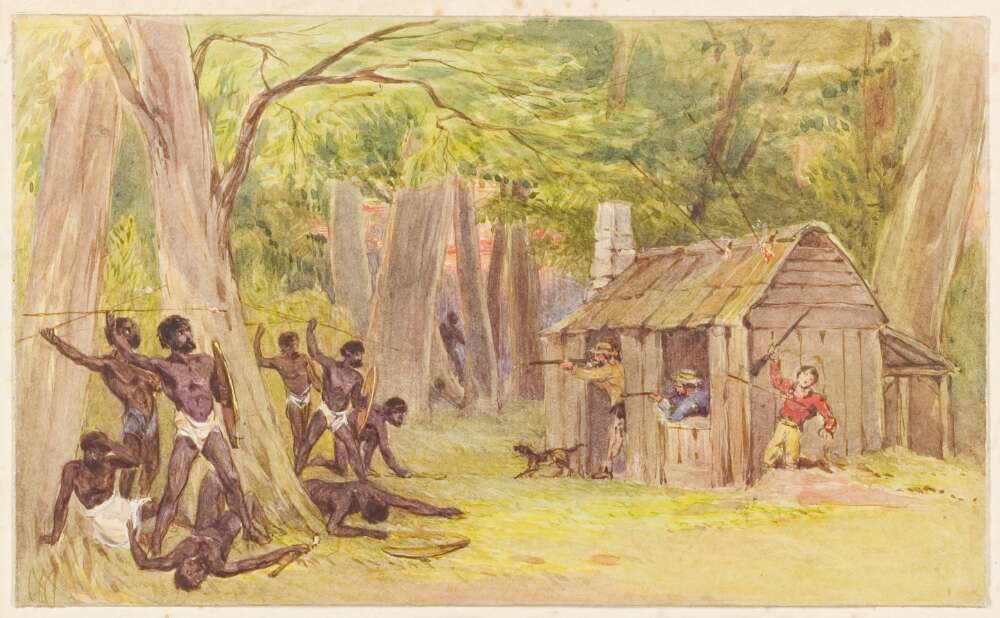

…I am now convinced these are the [Tasmanian Aboriginal] people that had fired the hut…at Mr Barnes’s near Launceston, and that the cause of [these Tasmanian Aboriginal people] being in that part of the territory was to look for their companions, and that not finding them there they set fire to the hut in sight of Launceston in defiance, and then set off to their own country, supposing they might have reached there, and made those smokes as a signal for them; and this must have been the case for the fires that they made were not general, therefore they could not be burning off and indeed there was no bush to set fire to as it was all burnt before, but several miles apart.

Aborigines attack a settler’s hut in VDL. National Library of Australia NK1300 [8]

“Horrid Murders by the Aborigines” Colonial Times, Hobart, 27 March 1829

On Friday afternoon, a Settler named Thomas Miller, residing on the East Bank of the North Esk, on returning home, found to his surprise, a quantity of his goods laying about the front of the house, and on entering which, he perceived some boxes had been broken open, and the contents strewed about the floor; on going up into the loft to search, for his wife, who was missing, he perceived ten or twelve of the blacks coming towards the house, about a hundred yards distant, upon which he immediately ran out, when several of them pursued him he had left a short distance from the house a cart and bullocks and on turning his head he perceived one of the blacks running after the cart, as the bullocks had taken fright and galloped off.

He made the best of his way to the nearest neighbour’s where he procured fire arms, and the assistance of Mr. Tower, who accompanied him back to his house. When they arrived near home, they perceived two men, who having heard that the blacks were at Miller’s house, had proceeded thither, a short distance from which they perceived his unfortunate wife with scarcely any signs of life as she was scarcely breathing, and were washing her face when Miller and Towers came up. They placed her on a bed, and brought her into the house, but by this time life was extinct.

On searching round about, they found about 20 yards from the house, the body of an unfortunate man, named James Hales, he was quite dead, having been speared through the lungs, and also in several parts, of his body; on looking further they found the body of Thomas Johnson, he was also lifeless, having no less than 11 spear wounds in his back, and his neck dislocated by blows; supposed to be by the waddies of these sable destroyers.

The death of the woman was occasioned by a dreadful blow on the back of her head, and she was likewise beat and speared, in several places, stripped of everything she had on except her stays. They robbed the house of a musket, 150 lbs. of flour, 100 lbs of sugar, a canister of powder, all the linen and bed clothes, and in fact of almost everything moveable. The cart, which had 7 sheep in it, he found safe, about 300 yards from the place where he left them.

The same day, about a mile from the same place, they robbed the house of a settler named Russell of every moveable article, and likewise speared a man on the threshing floor, who ran away to a neighbouring hut, near which they speared another man named John Burke who had been to Mr. Russell’s for some flour, which he was carrying in a bag ; they drove the spear through the bag into his loins, he then dropped it, and made to the nearest hut. They also robbed the hut of John Carns of flour, and all it contained. On Saturday an Inquest sat upon the bodies, when the verdict returned was “wilfully murdered by some of the Aborigines, at present unknown –

Notes and references

[1] Dr Nick Brodie calls the conflict the ‘The Vandemonian War’, in the same way that Aotearoa/New Zealand renamed the conflicts that took place between 1845 and 1872 between the New Zealand colonial government and Māori peoples. See Brodie, N. (2018). The Vandemonian War: The secret history of Britain’s Tasmanian invasion. Hardie Grant Books.

[2] For the story of Kikatapula’s complex life see Lyndall Ryan’s Tasmanian Aborigines: A history since 1803 (2012), Allen & Unwin; and Robert Cox’s Broken Spear: The untold story of Black Tom Birch, the man who sparked Australia’s bloodiest war (2021), Wakefield Publishing.

[3] Guerrilla warfare is a form of irregular warfare in which small groups of combatants, such as paramilitary personnel, armed civilians, or irregulars, use military tactics including ambushes, sabotage, raids, petty warfare, hit-and-run tactics, and mobility, to fight a larger and less-mobile traditional military.

[4] Henry Reynolds & Nicholas Clements (2021). Tongerlongeter: First Nations leader & Tasmanian War Hero, NewSouth Publishing.

[5] Woodberry, J. (1972). Andrew Bent and the freedom of the press in Van Diemen’s Land. Fullers Bookshop.

[6] See L. L. Robson, ‘Brady, Matthew (c. 1799–1826)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, National Centre of Biography, Australian National University, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/brady-matthew-1822/text2089, published first in hardcopy 1966.

[7] The panels were mistakenly thought to have been produced during the administration of Lieutenant-Governor Thomas Davey and are sometimes incorrectly labelled as ‘Governor Davey’s Proclamation to the Aborigines’. Originally conceived by Surveyor General George Frankland as a way of communicating the proclamation to Aborigines, they were issued by Governor George Arthur between 1828-1830, during the Black War. The boards were mounted on trees in remote areas of Van Diemen’s Land where it was intended that Aboriginal People would see them.

[8] This illustration was published as the plate facing p. 51 of James Bonwick’s Last of the Tasmanians (1870). https://nla.gov.au:443/tarkine/nla.obj-135224743