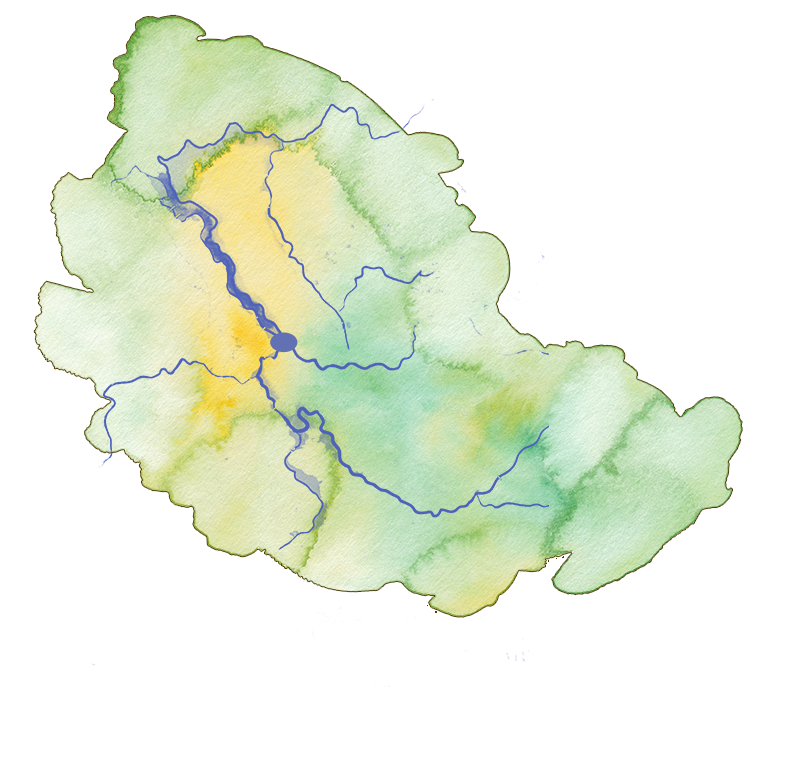

Eels of the Tamar/Kanamaluka estuary

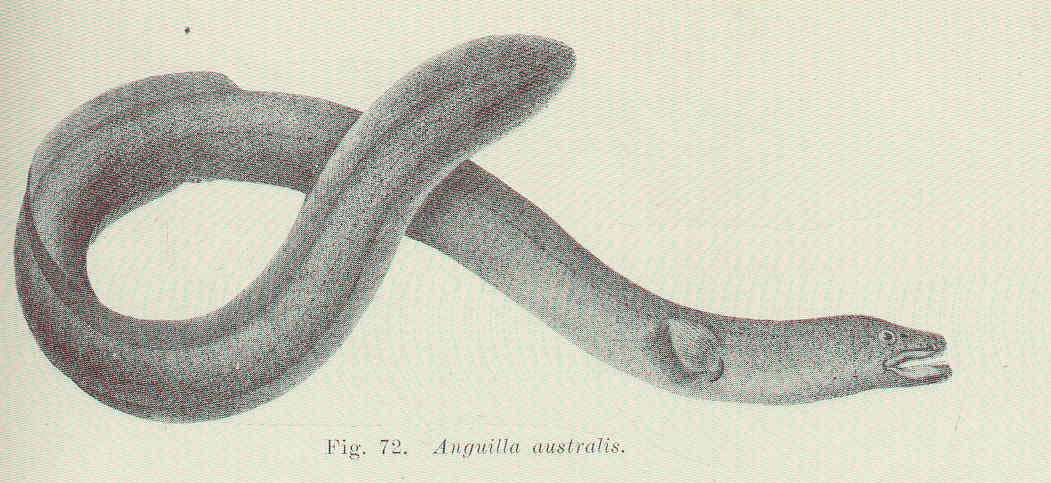

The freshwater ways of Tasmania have abundant populations of eels, and they were an important food source for people, before and after colonisation. In the streams and rivers around Launceston the most common species of eel was, and still is, the Short-finned Eel (Anguilla australis).

This eel can grow up to 3 kilograms and it can live for up to 24 years, spending around 14 years in freshwater. Eels are ecologically important in Tasmanian inland waterways because they are our largest, native, freshwater fish.

Short-finned eel (Anguilla australis). Wikimedia Commons.

One of the amazing things about eels is how long it takes them to reach full maturity; usually around 6 years but often up to 10 years, and females can take between 10 to 20 years. When they are ready to spawn, the eel’s digestive system shuts down and it then migrates to salt water. This is a journey of around 3000 kilometres north to the Coral Sea.

The females give birth to hundreds of thousands of baby eels that begin life as transparent larvae; then the mother eel dies. The larvae ride the tidal currents southward on their journey toward waters closer to where their mothers came from. These small creatures have this location information imprinted in their DNA so they instinctively migrate to, and follow, major rivers and estuaries into smaller habitats.

As they spend more time in the estuaries and rivers and streams, the larval eels (called ‘glass eels’ at this stage because they are still transparent) start to become darker in colour. It is at that stage they are known as known as ‘elvers’.

Short-finned Eels are mainly carnivorous (‘meat’ eaters); they feed on small fish, molluscs, and water-borne larvae of various other creatures. They feed mainly at dusk and into the night and forage around shorelines for food.

Archaeological and cultural evidence from places Like Lake Condah (Budj Bim) in Victoria tell us that for thousands of years, Aboriginal People cultivated eels as a food source and a valuable trade item. The eels were smoked, which preserved them for some time so they could be a regular part of their diet.

Follow this link to find out how the Gunditjmara People of southern Victoria built the Budj Bim eel trap system around 7,000 years ago. https://deadlystory.com/page/culture/history/Gunditjmara_people_build_sophisticated_Budj_Bim_eel_trap_system

Studies have shown that Aboriginal People of south-eastern mainland Australia had similar cultural practices to Tasmanian Aboriginal People. It is therefore reasonable to deduce that Tasmanian People would also have used eels as a valuable source of protein, especially when they were so abundant in the local waterways of the Launceston estuary.

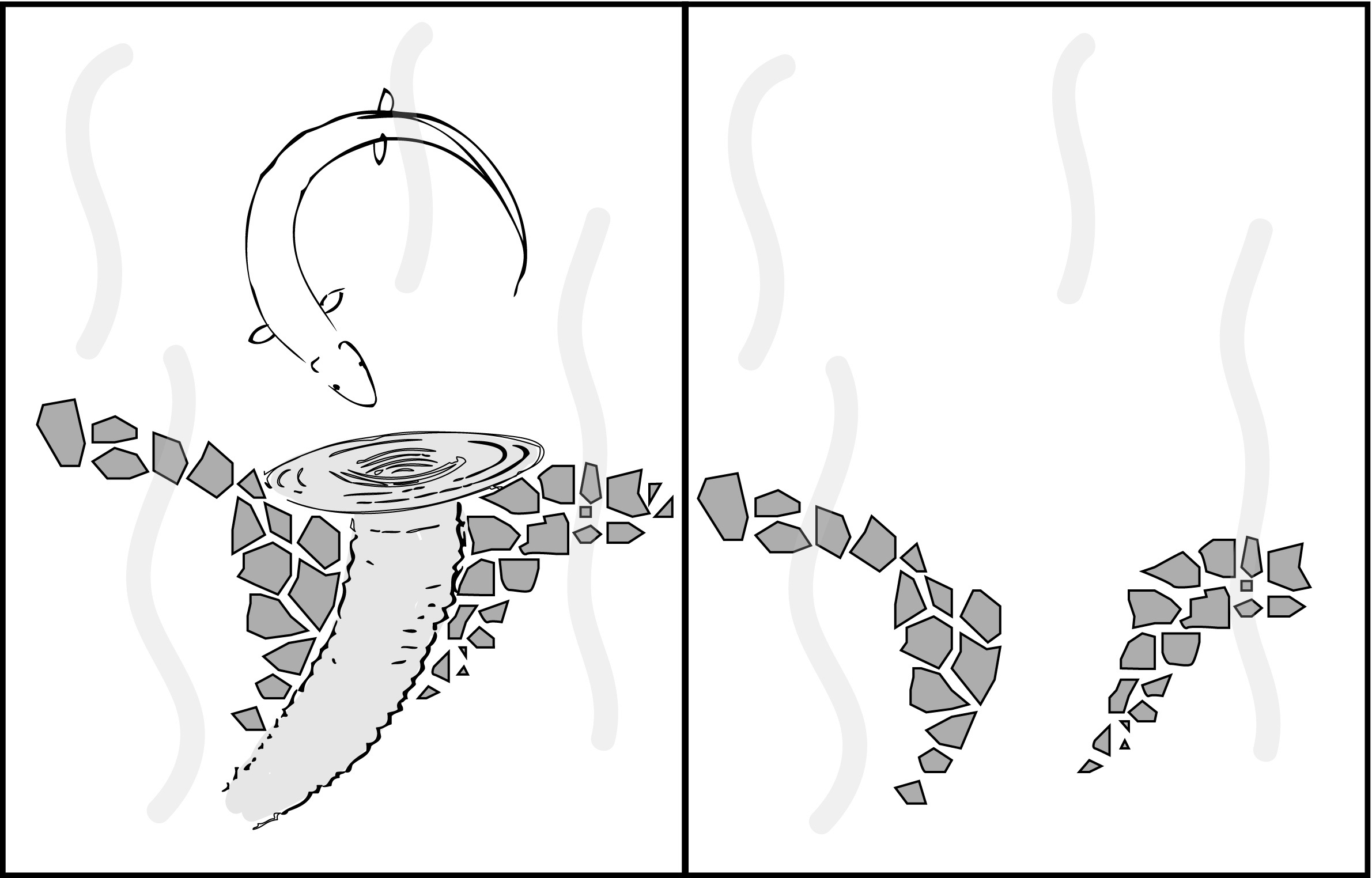

Aboriginal People made woven eel traps from reeds and grasses (B. Wood)

To catch the eels, Tasmanian Aboriginal People may well have used the same type of woven conical shaped traps used at Lake Condah, made from local materials such as River Reed, Sagg, Blue Flax Lily and White Flag Iris.

Eels have a very tough, and slippery, skin so it can be difficult to grab hold of them (hence the expression, ‘As slippery as an eel’). Like Aboriginal People on the mainland, Tasmanian Aboriginal People must have overcome that issue and found a trusted method for trapping eels.

Another species of eel that is found in freshwater rivers is the Long-Finned Eel (Anguilla reinhardtii). This species is Australia’s largest freshwater eel. It is much larger than the Short-finned Eel; it grows to around 20 kilograms in weight and lives for up to sixty years. Like the Short-finned Eel, the Long-finned Eel also migrates out of the river systems it inhabits when it is ready to spawn and makes its way to the Coral Sea area where each one can spawn hundreds of thousands of larvae.

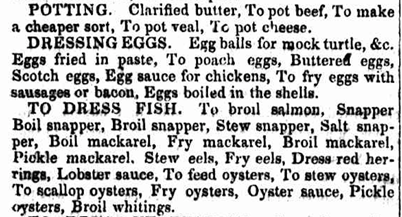

An advertisement listed the 1843 book’s recipes, including stewed and fried eel (Trove)

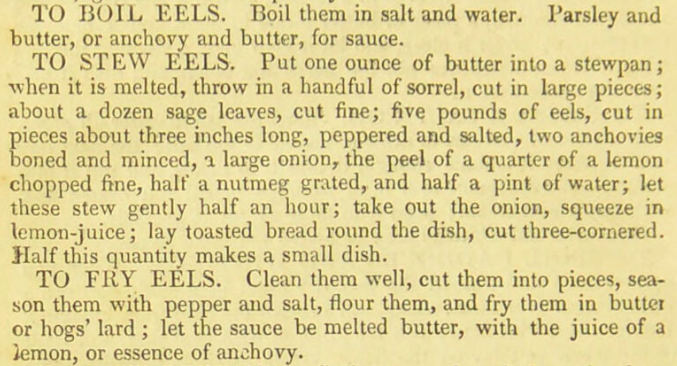

Eel recipes from the 1830 English cookbook (Wellcome Collection)

Today, many people don’t like the look or taste of eel and refuse to eat it. However, in England, a cookbook written by a Mrs Deborah Irwin dated to the 1830s, called The Housewife’s Guide; or an Economical and Domestic Art of Cookery [1] had recipes for eel, showing that Europeans of those times were also fond of eating them.

An 1843 newspaper advertisement, apparently for an Australianised version of the cookbook, noted that it provided many delicious recipes for cooking eel and other seafood. In 1844 the Australian version was advertised as Mrs Irving’s Housewife’s Guide, and it may be the earliest Australian cookbook.

Seals in Cataract Gorge

As the tiny eels made their way back through Bass Strait to estuaries and river systems from January to May, they attracted the attention of seals who lived on the rocky islands in Bass Strait. Seals would then follow the food trail of the eels into some of the smaller rivers and streams, often ending up as far inland as the Cataract Gorge. Even today you can see seals frolicking in the water and sunning themselves on the rocks in the Gorge during the summer.

Seals were a valuable source of food for Tasmanian Aboriginal People. They would usually target the young and at one site on the far west coast of Tasmania, Bluff Hill Point, it is possible to see where the Aboriginal People constructed a rather complex bank of stones to create a wall above the shoreline that they would hide behind as they waited for the young seals to come up the shore.

Seals prefer rocky terrains and as the young basked in the sun the hunters would come from behind the wall and kill the seal quickly, most likely using a blow to the head with waddy. The carcass would then be dragged back behind the wall and into hollowed depressions in the rocks where they would be processed.

Australian fur seals basking in the sun on rocks (Wikimedia Commons)

Eels and seals were integral to Tasmanian Aboriginal life and a valuable source of much-needed nutrition. Tasmanian Aboriginal People had complex means of harvesting and processing these animals which was done on a sustainable basis in order to maintain stocks of the food sources for the future.

Seals were a valuable source of protein and fat that could be mixed with ochre and smeared over the body as a means of insulation in colder weather and sun protection in the summer.

The main species of seal that makes its way to Cataract Gorge is the Australian Fur Seal. Males can live for up to 18 years and females can live as long as 27 years. Males can grow to a weight of over 200 kilograms which can pose problems when the seals follow the elvers and glass eels along rivers and streams that flow into suburban areas.

The Examiner, December 27, 2016.

They can also end up in places not meant for seals, such as on someone’s car parked in their front yard! In 2016, a 200kg male Australian Fur Seal found its way into the front yard of a house in the Launceston suburb of Newstead and decided to use the owners’ Toyota Camry as a sunbed. It did not go well for the Camry, but the enormous seal, called Lou Seal by the police, did get some coverage in the local media.

Notes and references

[1] Newling, J., & Vincent, A. (2022). Fern syrup, stewed eel and native currant jam: this 1843 recipe collection may be Australia’s earliest cookbook. The Conversation, April 27. https://theconversation.com/fern-syrup-stewed-eel-and-native-currant-jam-this-1843-recipe-collection-may-be-australias-earliest-cookbook-181789