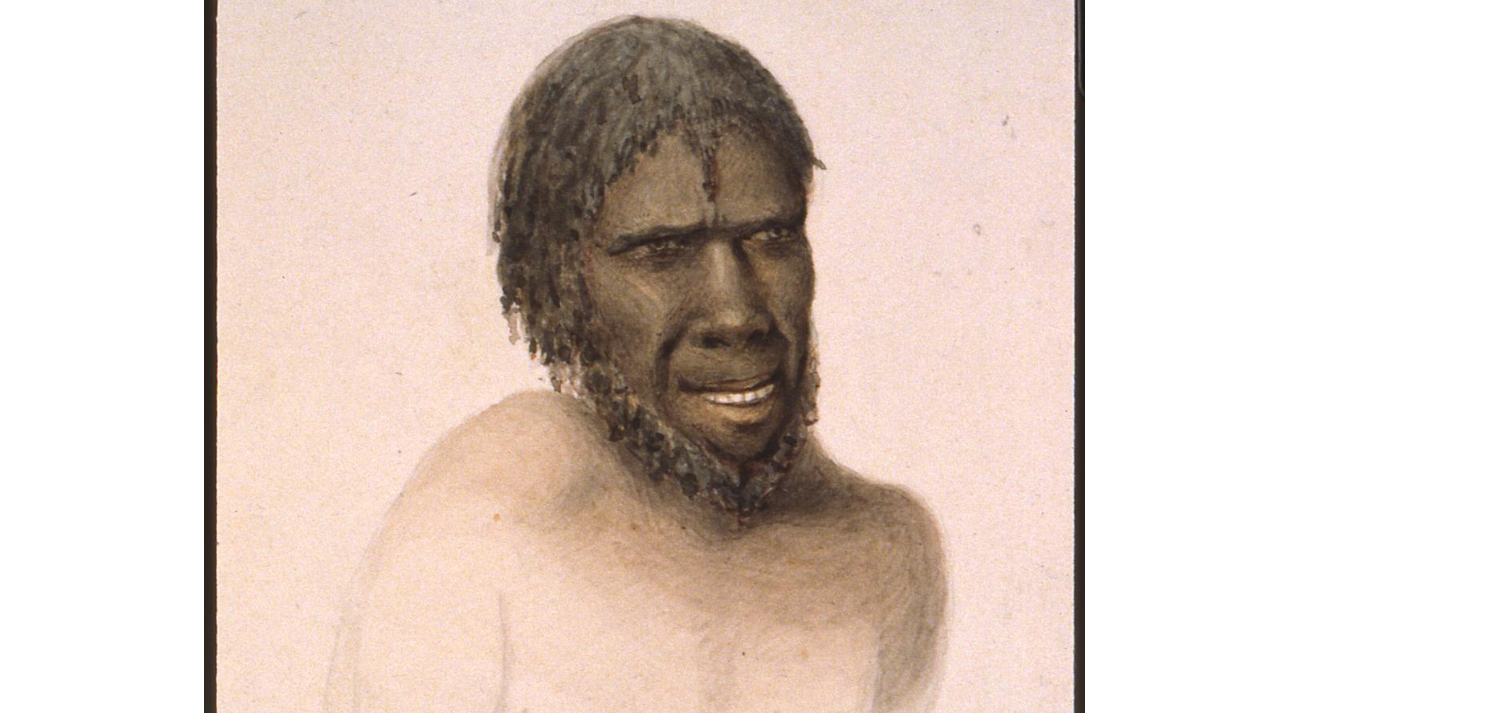

Watercolour drawing of Moleteheerlaggenner (aka Eumarrah) by Thomas Bock. British Museum. 1832.

Moleteheerlaggenner (aka Kahnneher Largenner and Eumarrah) is believed to have been born in 1798, around 5 years before the British colonisation of Van Diemen’s Land began in 1803. This was the time of ‘first contact’, when the sealers/whalers were harvesting seals on the windswept islands of the often-tumultuous Bass Strait, so as a child, Moleteheerlaggenner may well have heard about the arrival of strange, white skinned men arriving on floating islands.

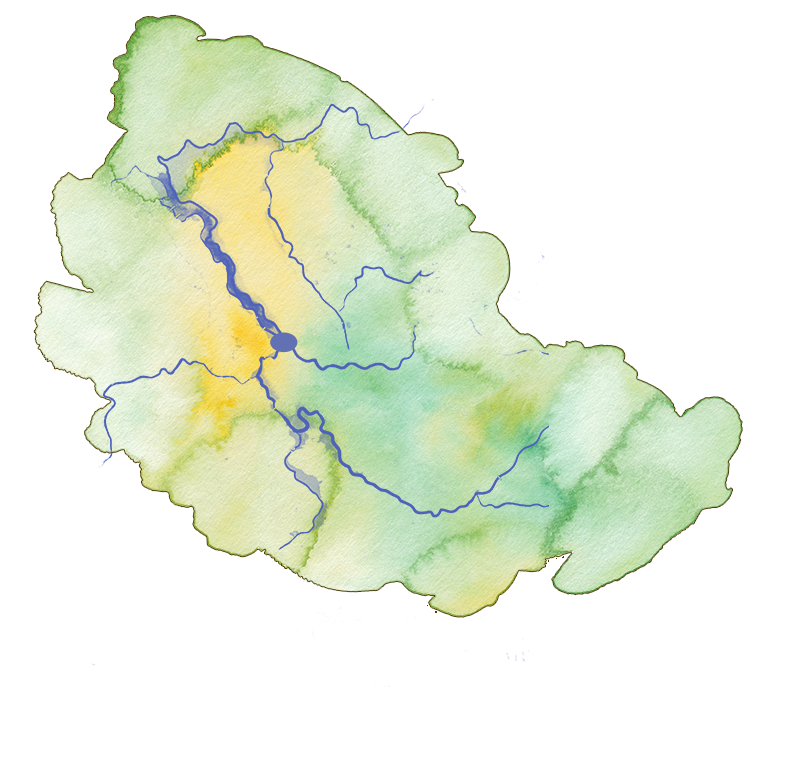

Moleteheerlaggenner’s people were the tyerernotepanner of the Midland Nation (aka Stoney Creek Nation). The area was also occupied by the leterreermairrener and panniher peoples. All three groups would have moved from place to place on a seasonal basis, but it is generally accepted that the tyerernotepanner occupied the area of the Midland Plains around what is now Campbell Town for much of the year. They probably moved north along the Kanamaluka/Tamar River to the Bass Strait coast during the colder times of year.

Moleteheerlaggenner grew up during turbulent times. During his short life he witnessed the devastation caused by the invasion of Aboriginal lands by strange people and animals.He would have seen and heard of the increasing deprivations, murders, kidnapping and rape of his people.

There is an old saying: keep your friends close and your enemies closer, and Moleteheerlaggenner was shrewd enough to see the advantage of working closely with the strangers as a matter of survival.

Moleteheerlaggenner was employed by Scottish farmer and wine and spirits merchant Hugh Murray (1789-1845) who had a large property called ‘St Leonards’ on the Macquarie River near Campbell Town. The name ‘Eumarrah’, by which Moleteheerlaggenner is more commonly known, is probably a version of the name of his employer Hugh Murray, given to him by the colonists. [1]

The Black War

When the Black War eventually erupted into full-scale conflict in 1826-27 in the Midlands and out to the East Coast, Moleteheerlaggenner rejoined his people. He became a dynamic and effective leader in the conflict with the colonists. He probably used his knowledge of the customs and language of the colonists to his advantage.

In the closing months of 1828 Moleteheerlaggenner and his wife Laoinneloonner, were captured by a roving party led by Gilbert Robertson. It is most likely the only thing that saved their lives was the bounty of five pounds per adult (and two pounds for a child) that Robertson would have been only too keen to claim from the Government. [2]

The threat of capture did not seem to dull his appetite for vengeance, and on the On 22 November 1828, the Hobart Town Courier reported that the ‘King, named Eumarrah . . . declares it his determined purpose . . . to destroy all the whites he possibly can, which he considers a patriotic duty’. [3] Notably though, both he and others captured with him when giving testimony to the Executive Council on 18th of November 1828 denied killing anyone.

That denial did not stop Moleteheerlaggenner being imprisoned for a year in the Richmond Gaol. That year spent away from his people and the war must have been incredibly testing for the resistance leader.

Robinson’s ‘Friendly Mission’

However, rather than go back to war against the invaders after his release in 1830 he took a different tactic and joined George Augustus Robinson on his ‘Friendly Mission’ to negotiate a truce, or peace, with the Aboriginal people, who had the whole colony in a state of fear. [4]

Both Robinson and Arthur had hoped Moleteheerlaggenner would become an agent for reconciliation, and his agreement to do so may well have saved him from more gaol time. However, he never subordinated himself to Robinson and took the opportunity to abscond from his party in May of 1830. [5] Moleteheerlaggenner demonstrated his knowledge of the land, by trekking from Trial Harbour on the remote north west coast back to his homelands in the north and Midlands.

Oddly though, he presented himself to authorities in Launceston just a few months later in October 1830. This may have been because he had heard about the Black Line that was about to be launched to herd the people of the Oyster Bay and Big River Nations far south and trap them on a thin isthmus at Eagle Hawk Neck.

At Governor Arthur’s request Moleteheerlaggenner joined the Black Line as a tracker, but his reason for agreeing to join the enemy soon became clear when he fell in behind the line and began attacking colonists in the Tamar and Esk Valleys. [6]

Moleteheerlaggenner eventually met up with Robinson again, who was still gathering up the remaining Aboriginal People for his ‘mission’ and helped him negotiate with the Big River people between October 1831 and January 1832. However, Moleteheerlaggenner and the other Aboriginal resistance fighters, played a blocking role and often led Robinson in circles and away from the people he was so keen to negotiate with.

At night Moleteheerlaggenner would take great delight in singing about his exploits in the war and his ‘amorous’ adventures.[7] Even though Moleteheerlaggenner readily swapped sides to help his people, Robinson still saw him as a valuable envoy. He travelled with Robinson to Hobart, then to Launceston and over to Flinders Island.

Moleteheerlaggenner was allowed to return to Launceston in 1832 but he became severely ill with dysentery and died in the hospital on the 24 March 1832. He was buried in St Johns Graveyard (most likely the Cypress Street Cemetery), with both Aboriginal and European ceremonies in his honour. [8]

[1] Murray, H. M. (1967). ‘Murray, Hugh (1789–1845)’, Australian Dictionary of Biography, https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/murray-hugh-2495/text3363.

[2] Harman, K. (2018). Explainer: the evidence for the Tasmanian genocide. The Conversation. https://theconversation.com/explainer-the-evidence-for-the-tasmanian-genocide-86828

[3] Roe, (2012). Eumarrah (1798-1832). Australian Dictionary of Biography. https://adb.anu.edu.au/biography/eumarrah-12905

[4] Ibid.

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ibid.

[8] Ibid.