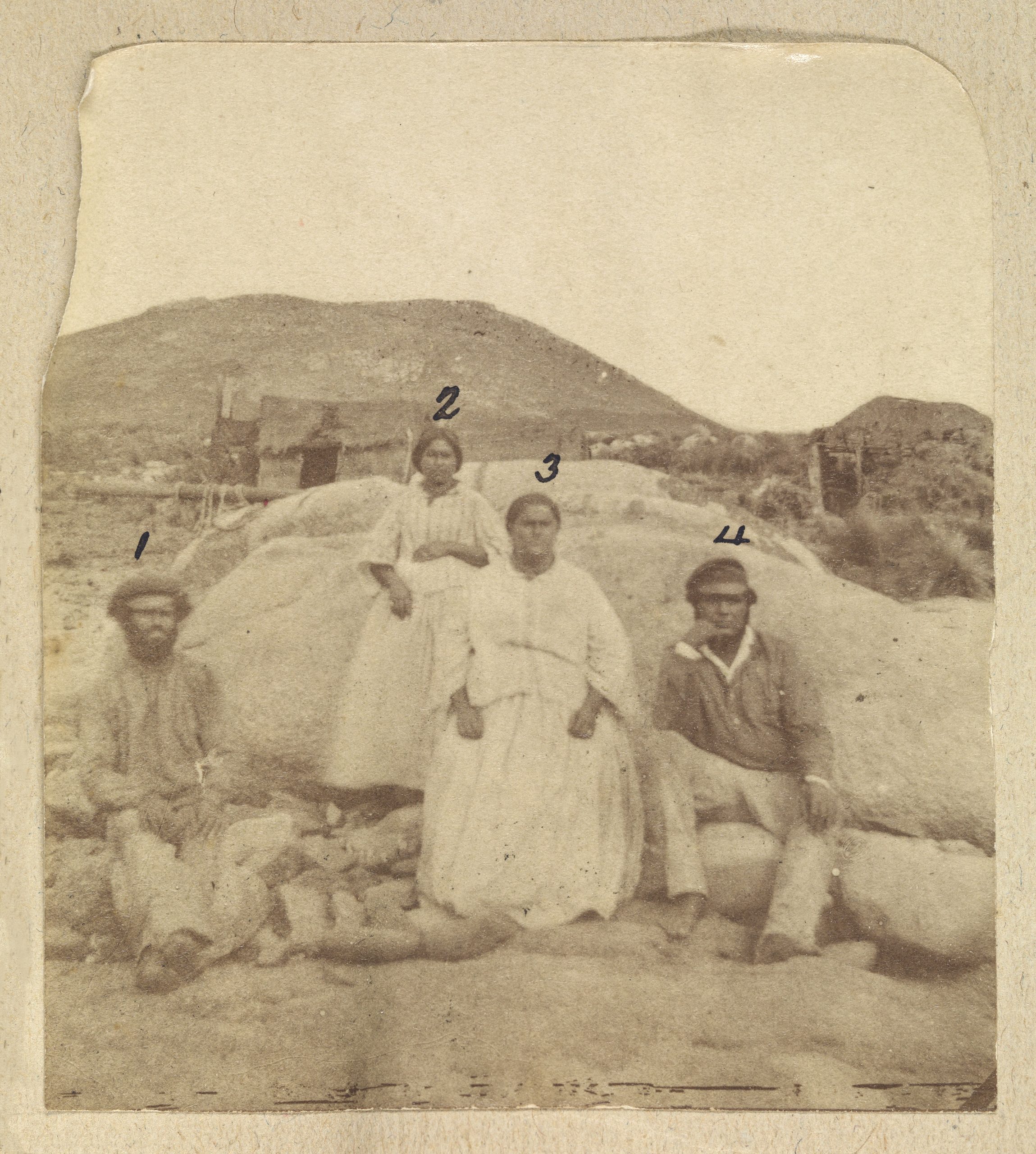

Lucy Beeton was born and lived her life in the Bass Strait Islands. She was called the ‘the Commodore’ because she regularly sailed into Launceston with a fleet of boats to sell mutton birds and their eggs, feathers, fat and oil. Lucy was also affectionately known as the ‘Queen of the Isles’ because of her passionate advocacy for the rights of the wider Bass Strait community. One of her greatest achievements was to establish a school to educate the children on the islands.

1 Mr Henry Beeton (brother), 2 Mrs Henry (Sarah) Beeton (sister-in-law), 3 Miss Lucy Beeton, 4 Mr James Beeton (brother)

Birth and family

Lucy was born on the 14 May 1829 at Gun Carriage Island (now known as Vansittart Island), located in the often tumultuous and windswept seas of Bass Strait. Her mother Emmerenna (English name: Bet Smith) was one of the daughters of Aboriginal leader, Mannalargenna. Her father was Thomas (aka John) Herbet, more commonly known as Thomas Beeton (alternate spellings; Beedon, Baden or Beadon). Thomas had been a sailor in the British navy, was convicted of mutiny and sentenced to seven years’ transportation in 1817. When his sentence was completed, he moved to Bass Strait in 1824 and became a sealer.

The Bass Strait sealing industry

Sealers began plundering the Bass Strait fur and elephant seal populations in 1798. Fur seals were hunted for their fur that was made into garments and boots, while elephant seals were hunted for their oil. These highly valuable products were traded across the Pacific Ocean and sold in markets in England, India and China. [1]

The sealers were a diverse group made up of ex-convicts, sailors and whalers from England, Scotland, and the United States. Some of the Aboriginal women who worked in the sealing industry were seasonal labourers ‘hired out’ by leaders like Mannalargenna in exchange for hunting dogs. Other less fortunate women, like Trukanini’s sister, were brutally kidnapped and forced to live with the sealers and work as slave labourers.

Some of the sealers treated the women kindly and established families with them; others treated the women as slaves and punished them brutally. One of the sealers told George Augustus Robinson that, ‘Sir, if we detect them doing wrong they get flogged for it, but you know Sir, not violently’. There is also an account of a sealer shooting an Aboriginal woman in the chest because she failed to clean mutton birds correctly. [2] The sealers became known as ‘Straitsmen’ and the Aboriginal women who lived with them called themselves tyereelore, or island wives. They are the ancestors of many Tasmanian Aboriginal People today.

The Black War

When Lucy was born in 1829, it was a time of great upheaval and dislocation for Tasmanian Aboriginal people as the Black War was still being fiercely fought primarily in the Midlands and East Coast in the lands of the Stoney Creek Nation and Oyster Bay Nation. However, the dire ramifications of the conflict were felt all over the island by Aboriginal People and colonisers. The Straitsmen and Aboriginal women and children who lived on the Bass Strait Islands were somewhat insulated from the worst effects of the Black War. By 1831 these families had become well established on Gun Carriage Island. They lived in cottages, tended vegetable gardens, and continued to hunt seals and mutton birds (Short Tailed Shearwater; Aboriginal name is yolla).

Drawing of Miss Lucy Beeton and her cottage on Badger Island

Businesswoman and political activist

Lucy became a significant advocate for Aboriginal People in the Bass Strait Islands. That may have been due to Lucy being well educated by private tutors during the time she spent at George Town or Launceston. Her father also taught her the skills of political activism, sailing and business.

In the 1850s, Lucy and her father, in conjunction with the other islanders, lobbied the Tasmanian government to have land with mutton bird rookeries on it given to them. They considered this to be just compensation for Aboriginal people having their lands invaded and stolen from them on mainland Tasmania.

The government refused the request, as it also did with the plea to have a Christian teacher for Gun Carriage Island financed by what was known as the Land Fund. Lucy’s response was to appoint herself as the teacher as she was both well-educated and a strong believer in the Christian faith.

Lucy was forced to put her teaching to one side when her father fell ill around 1862. She cared for him until his death in that same year and then she then took over the family business. That same year Lucy invited the Anglican Archdeacon of Launceston, Thomas Reibey, and the Anglican Minister of the church at George Town, George Fereday, to the Islands to discuss having a schoolteacher for the 66 children living on the Islands. Reibey took that request to the Tasmanian State Government who agreed to provide 250 Pounds, on the condition the Islanders raised the same amount. When that proved unattainable Lucy took it upon herself to appoint two teachers from Melbourne.

First Tasmanian Aboriginal teacher

In 1871 and still receiving no support from the Tasmanian Government for a school, Lucy decided to begin a school on Badger Island. It was a rather humble beginning for the school with lessons conducted inside a tent. In 1872 the Tasmanian Government finally agreed to support the school and provided a teacher. Lucy’s continued campaigning to get the school in order to ‘instruct and civilise’ the Island children was rewarded with a lifetime lease of Badger Island (where she spent most of her life) at an annual fee of 24 Pounds.

The Lucy Beeton Aboriginal Teacher Scholarships for the Bachelor of Education and Master of Teaching courses were established at the University of Tasmania in recognition and honour of Tasmania’s first Aboriginal teacher.

Maireener shell necklace made by Lucy Beeton, QVMAG Launceston

Lucy Beeton’s legacy

Lucy never married and shared her homestead on Badger Island with her two brothers and their families. She became a second mother to their children and had a favourite niece, Isabella. In 1886 Lucy was diagnosed with ‘congestion of the lung’ and passed away at age 57 on the 7 July 1886. She was buried on the east coast of her Badger Island home.

Lucy’s influence among the Bass Strait Islands and their people was far more widespread than the campaigning for a school and teachers. She rallied hard to stop the exploitation of her people by white traders who instead of offering cash payments for produce gave the providers cheap alcohol.

Lucy also controlled the trading operations of her community and was regarded by many as the ‘Queen of the Islands’. In addition to that nickname, Lucy was also called ‘The Commodore’ because she regularly led a small flotilla of ships into Launceston laden with produce from the Islands, including mutton birds, their eggs, feathers, fat, and oil. [3]

Primary sources

Friendly Mission. The Tasmanian Journals and Papers of George Augustus Robinson 1829-1834, Edited by NJB Plomley, QVMAG and Quintus Publishing 2nd Edition, 2008.

Entry for 31 March 1831, page 366

[Lucy’s mother Emmerenna]…WORE.TER.NEEM.ME.RUN.NER TAT.TE.YAN.NE alias Bet Smith had lived with Thomas Beadon about five years by whom she has had two children. One is dead, buried at Preservation Island; the other [Lucy] is living and is with her mother at the establishment. She is now with child. Beadon delivered her up to the establishment 29 March 1831. She was taken from the main by a sealer named John Harrington who was drowned. Beedon obtained her from Tucker about five years since, probably purchased her. This woman is a native of Big Mussel Roe, called PRE.LOO.NER, and belonged to the nation inhabiting this district called TRAWL. WOOLWAY. WAT.TE and PUNG and PLEEN.PER.REN.NER belonged to the same.

…During our stay here we visited, in a sealer’s boat, Badger Island; this isle is a fair specimen of the smaller islands, which, as regards pasturage are superior to the larger; it is tolerably well grassed and timbered with she-oaks, there is, however, a scarcity of water.

This island [Badger Island] has the honor of being royal territory, it belonging (by consent of V.D.L. Government) to Miss Lucy Beadon, the Queen of the islands, a young lady of Gipsy complexion, good address, majestic carriage, kind disposition, polite, affable, 26 years of age, and weighs 23 stone. (The Archdeacon was very anxious that he should have the pleasure of performing another ceremony between Miss Lucy and myself – What a prospect! I acquit the Archdeacon, however, of any previous knowledge of my being already chained.) Miss Lucy is the proprietress of 500 sheep, some cattle, and some goats. Her Majesty had the advantage of an education when young, at a school in Launceston, and she, with good nature and intention, imparts her knowledge to the younger members of her territory, when opportunity offers. Her father, a dweller in these islands for fifty years, is one of the patriarchs I have spoken of. Miss Lucy has two brothers and a sister, who, though not so majestic in proportions as herself, are still much beyond the usual average.

Lucy Beedon (or Beadon, or Beeton) was the most notable personality produced by the second generation of islanders. Although a spinster, she maintained a matriarchal sway over the scattered families from her ‘seat’ on Badger Island. Born on 14 May 1829, Lucy was the first child of James Herbert Beedon ( or Beeton), a London Jew who, as Thomas Baden, was sentenced to seven years’ transportation in 1817. Lucy’s mother was Emmerenna,… of the Cape Grim tribe. The family was living on Guncarriage Island at least as early as 1831. Second generation Beedons were on Badger Island at least from the early 1860s.

‘Town Talk and Table Chat’ (1863, December 9). The Cornwall Chronicle, page 4. Retrieved July 29, 2020, from http://nla.gov.au/nla.news-article72193637\

His Excellency the Governor received at about 1 o’clock yesterday, a deputation of the Islanders from the Straits, consisting of Miss Lucy Beadon, her sister-in law Mrs. Beadon, and Mr. Everet, accompanied by their schoolmaster Mr. Richardson. The Islanders were introduced to His Excellency, who received them very graciously, by Mr. Murray, M.H.A. Colonel Browne, who was attended by Captain Steward, A.D.C, shook the Islanders warmly by the hand, and desired them to be seated. He entered into a conversation with them as to their necessities, which he noted down, and intimated that he should have great pleasure in personally interesting himself on their behalf. After a conversation of about twenty minutes the Islanders withdrew.

… I spent the evening at Miss Beedon’s. I cannot here forbear mentioning a matter which shows that there is at least, one tender heart that feels a true sympathy for poor Lalla Rookh [nickname given by G.A. Robinson to Truganini], the very last of the Tasmanian aboriginals [sic]. In the course of conversation, Miss Beedon mentioned how much and how often she had longed to offer to Lalla Rookh [Truganini] a home where she might spend her remaining days among the descendants of her own race. I at once undertook to enquire at head quarters whether such an arrangement might be effected, should it also meet the wishes, as I expected it would, of Lalla Rookh herself. To this matter I gave immediate attention on my return to Launceston, forwarding to the Governor’s Private Secretary the written invitation Miss Beedon had addressed to Lalla Rookh, accompanying it with a few lines of explanation from myself, but I fear the kindly wish of Miss Beedon is not likely to be gratified…

Notes and references

[1] Patsy Cameron. 2011. Grease and Ochre, p. 93.

[2] Phillipa Mein Smith. 2019. The sealing industry and the architecture of the Tasman world, Fabrications, Vol. 29, No. 3, p. 3.

[3] Further reading: Shayne Breen & Dyan Summers. 2006. Aboriginal Connections with Launceston Places. Launceston City Council; Carol Raabus. 2011. Meet the Queen of the Isles: Lucy Beeton, 31 March 2011, ABC Radio Hobart.