The Tamar Valley has been an integral place for Tasmanian Aboriginal People for over tens of thousands of years. The very first people to come to Tasmania did so around 40,000 years ago. Archaeological evidence found at Parmerpar Meethaner at the head of the Forth River, just below Cradle Mountain in central north Tasmania confirmed that people were living in the rock-shelter, cooking and warming themselves with fire around 34,000 years ago.

At that time during the Ice Age, the landscape around Parmerpar Meethaner rock shelter would have been rocky and uneven. The landscape was covered by low, tussocky grasses, some with small flowers, and low-growing shrubs. The vegetation had adapted to the harsh conditions of a high-altitude environment and able to withstand extreme temperature fluctuations. The extreme cold forced people to seek out sheltered areas, such as rock shelters in the highlands; in the low lands, people moved to inland valleys close to coastal areas.

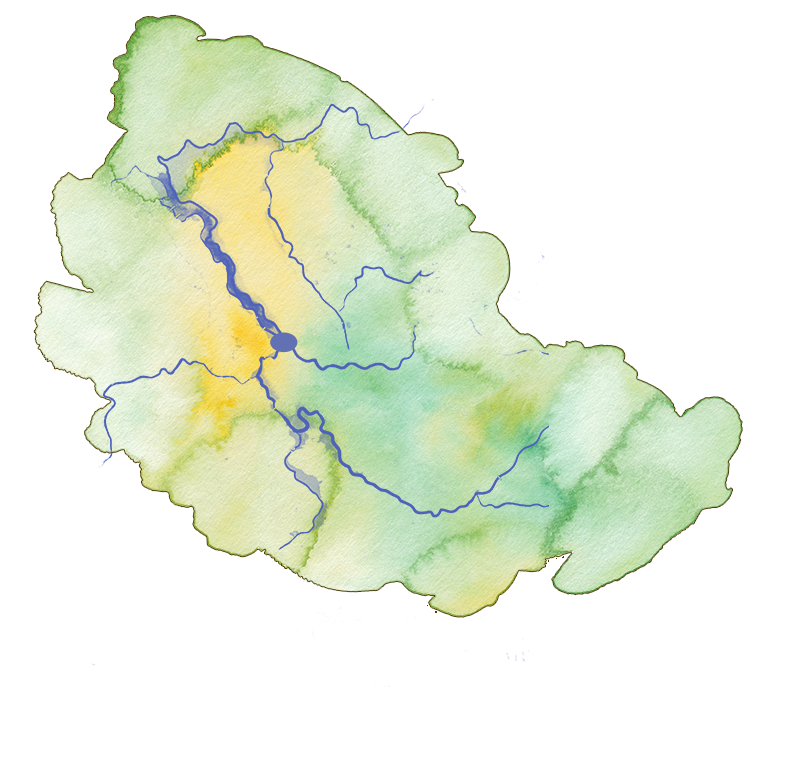

The Kanamaluka/Tamar Valley was one of the lowland areas and an attractive place for people as it was naturally sheltered by mountains to the east and large hills looming over the estuary to the west. The Kanamaluka/Tamar Valley was, and still is, home to a huge range of animals, plants, and other edible resources.

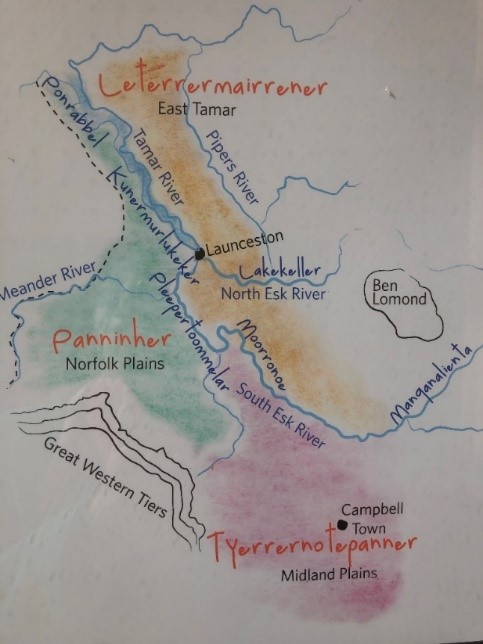

The lands around the modern city of Launceston were the Country of the Northern Midlands Nation (courtesy of QVMAG)

The importance of the area that now encompasses the city of Launceston is that it sits at the junction point of three major waterways, the North Esk River, South Esk River and Tamar Estuary. Long before colonisation, this area was a central place for people from different areas and nations to gather for ceremonies, celebrations, and cultural exchange.

Nations

The Kanamaluka/Tamar area was part of the large home territory of the North Midlands Nation. Historian Professor Lyndall Ryan estimates that there were probably at least five clans in this nation, but only three have been identified, the Leterrermairrener, Tyerrernotepanner and Panniher Peoples.

Once or twice a year, people from other nations made the journey to the Kanamaluka/Tamar region for major gatherings and ceremonies. The North Midlands Nation interacted with the North, North East, Big River, and Ben Lomond Peoples. Commentaries from early colonists indicate that most groups did not have friendly relations with the Oyster Bay Nation but did not explain the reasons why this was the case. However, alliances and rivalries changed and developed over time.

Trevallyn Reserve, a perfect meeting place for thousands of Aboriginal People before colonisation (photo: G. McLean).

For day-to-day living, people did things in smaller family groups of up to 12 people. Clans were extended family groups comprising around 100 people. Aboriginal People call people who are connected by family ties and who come from the same place or Country, ‘mob’.

Clans would come together a few times a year for celebrations and family gatherings, much like people do today for birthdays, anniversaries, Christmas and Easter times. Archaeological evidence and cultural knowledge from contemporary Aboriginal People indicate that gatherings of up to 1000 people would occur in high areas above Launceston in what is now the Trevallyn Reserve.

The area is over 200 metres above sea level and offers 360-degree panoramic views out as far as the Western Tiers, Mount Arthur and Mount Barrow to the east, north down the Tamar Estuary for at least 30 kilometres and the same to the south; a perfect place for large gathering of people.

The gatherings would be part of the seasonal movements of most people and occurred in the hotter months, just before the cooler weather and shorter days arrive.

Ceremonies

Marriage was one of the most important reasons for gathering and celebration. Although little is known about how a prospective partner was found, using accounts of similar events on the mainland, we can assume they had to choose someone from a different nation.

Many First Nations People today say they have ‘a mother country and a father country’. Having to find a partner outside the family group was a way of ensuring genetic diversity, which is essential for human survival. It also means First Nations People had to be multi-lingual and able to communicate with those outside, but close to, their home nation.

Trade

Another significant aspect of gatherings was trade. When archaeologist Sue Kee conducted a survey of Trevallyn Reserve in 1990, she found stone tools that were made from a metamorphic rock known as hornfels (singular noun) that is not found in the area. [1] This indicates that hornfels was probably traded for dolerite, the predominant stone of the Launceston area (and it is what forms the Cataract Gorge).

Dolerite would have been keenly sought by those outside the area because it is an extremely hard material. Pieces can be large and heavy but smaller balls make perfect grinding stones. Flat dolerite slabs were shaped to make an ideal grinding base.

An ochre, or ‘ballywinne’ kit in QVMAG.

Some people refer to these two types of stone tool as ‘ballywinne kits’. They were used to grind seeds into flour for making damper, and also to grind ochre that was a significant part of Tasmania Aboriginal culture.

Ochre was also a very significant trade item, and for more information about that refer to the section about ochre and its uses.

Notes and references

[1] Kee, S. (1990). Midlands Aboriginal Archaeology Site Survey. Occasional Paper no. 26. Department of Parks, Wildlife and Heritage.