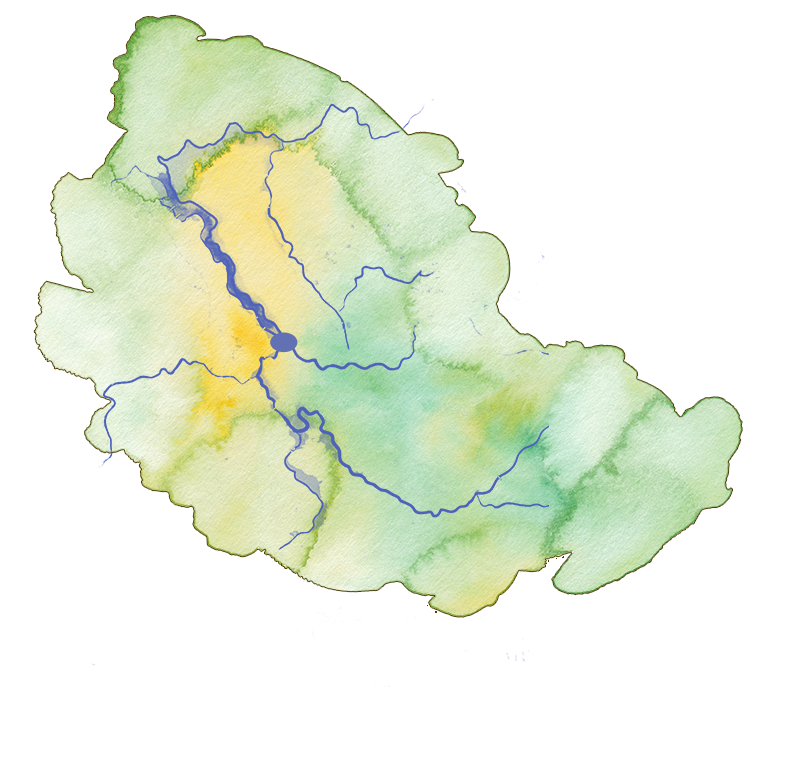

Location of ochre deposits in Tasmania (L. Zarmati adapted from B. Brimfield)

Ochre is a soft stone composed of haematite or iron oxide, which looks very much like dry clay. Aboriginal people made ‘paint’ by grinding the ochre and mixing it with a variety of animal fat, water, blood and/or saliva.

Ochre comes in many different colours that can be found in different places. It is estimated that Aboriginal people have been in the Kanamaluka/Tamar area for about 40,000 years, so they would have known about these sources of ochre. Ochre would have been a prized trading commodity, perhaps for access to another group’s country.

At least two Aboriginal ochre mines have been identified in the Kanamaluka/Tamar area: one at Beaconsfield and another at Rocherlea. The Rocherlea deposit was of yellow ochre which was mined by Aboriginal people.

Other colours, such as reds, greens, purples can also be found in different places in the Tamar Valley. There were many other ochre deposits mines all over Tasmania.

Black and red ochre is found in large deposits in the Gog Ranges/Alum Cliffs region near Mole Creek.

We do not know for certain how it was used for such things as initiation ceremonies because there are no written records of anyone witnessing these events, which were likely restricted or secret.

Red ochre was used by the men to adorn their hair and beards. It was the women who prepared and applied the ochre to the men’s hair and beards. In 1804 British explorer, Robert Brown, remarked of the men he encountered in the Kanamaluka/Tamar Valley,

The hair of the head was in most them covered which ochre by wch [which] in some especially in the lads the wool was divided into small parcels.

Faces of some were blackend [blackened] & in the colouring matter a considerable proportion of minute mica was contained.

Their arms & thighs were tatood [tattooed] & in many was an archd [arched] line across the abdomen… [1]

Ochre was not just for adornment but had a practical function, which was to keep lice, fleas and other bugs out of hair and beards. Red ochre was mixed with animal fat and smeared on the skin as a means of insulation in winter and protection from sunburn.

Robert Brown, who explored the area from Port Dalrymple down to Cataract Gorge in 1804, also described how the men’s faces were blackened and that the colouring used contained, ‘…a considerable portion of minute mica.’ [2] Mica is a mineral whose glittery reflective properties are still employed in modern cosmetics.

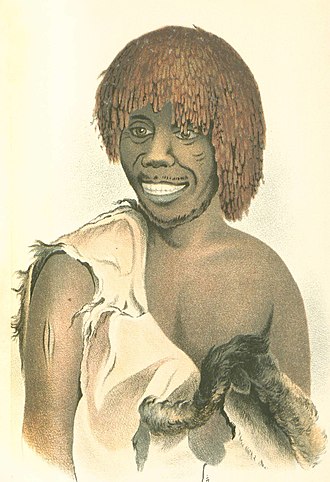

Portrait of Tunnerminnerwait by Thomas Bock, between 1831 and 1835,

In the portrait of Tunnerminnerwait you can see that his hair is heavily covered with red ochre. [3]

When colonists found the rich ochre deposit at Scott’s Hill, which is on Anderson’s Creek, 5.2 kilometres from Beaconsfield in the 1820s, they did not realise that Aboriginal people had been mining ochre there for thousands of years. In the twentieth century, ochre was an important ingredient used to provide a range of colours for paints. The Launceston’s paint industry began in the 1920s using material from the rich deposit at the Beaconsfield site.

Ochre is still extremely important for Tasmanian Aboriginal people today. It is used at ceremonies and events to create a connection to Country for participants. It is mostly used to paint stripes on the face, but other parts of the body, such as on the back of hands. Aboriginal dancers make extensive use of colours such as reds and whites, and it is also used by artists to create artworks.

School students can have a hands-on experience of painting with ochre by using this versatile natural pigment to paint on paperbark, water paper colour, or even on their face and hands.

Ballywinne

Dolerite was the most common type of rock found in the Kanamaluka/Tamar area and would have been keenly sought by those outside the area because it is an extremely hard material.

Pieces can be large and heavy but smaller, rounded balls make perfect grinding stones. Flat dolerite slabs were shaped to make a grinding base. Some people refer to these two types of stone tools as ‘ballywinne kits’.

Ochre or ‘ballywinne’ kit in The First Tasmanians exhibition, QVMAG Launceston

Aboriginal women made the grinding stones then they used them to grind seeds into flour for making damper, and also to grind ochre that was a significant part of their culture.

George Augustus Robinson, reported that the ‘mull’ or ‘ballywinne’ stone was carried by women, who also shaped them into useful tools:

The natives had employed themselves in manufacturing BALLYWINNE stones, a species of granite [dolerite], called…LARE.NER…Those stones are selected for their toughness and flat surface, and with those they bruise their red earth [ochre] for pomatum [paste for the hair]. In their wild state the women carry two each. They are one and half inches [about 4cm]. the women break off the round edge and give it a square edge. Their method of working the stone to this shape appears to me ingenious. The women I saw made a wet mark with their finger with spittle in the direction they wanted it broken, i.e., the edges taken off like a hexagon. They then put the edge of the stone in a small fire of charcoal and when sufficiently warm tapped it with a small stone and it broke in the direction required. [4]

Notes and references

[1] Macknight, C.C. 1998. Low Head to Launceston: The Earliest Reports of Port Dalrymple and the Tamar, p. 71.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Tunnerminnerwait (c.1812–1842) was a Parperloihener clansman from north-west Tasmania and resistance fighter during the Black War. He was also known as Peevay, Jack of Cape Grim, Tunninerpareway and renamed Jack Napoleon Tarraparrura by George Augustus Robinson. Tunnerminnerwait and fellow resistance fighter Maulboyheener were the first Aboriginal men on the 20 January 1842 to be executed in what later became the state of Victoria (See https://www.melbourne.vic.gov.au/about-melbourne/melbourne-profile/aboriginal-culture/Pages/tunnerminnerwait-and-maulboyheener.aspx).

[4] Plomley, N.J.B. 1966. Friendly Mission: the Tasmanian Journals and Papers of George Augustus Robinson 1829-1834, Tasmanian Historical Research Association, p. 897.