Does this amount to ‘farming’ or ‘agriculture’?

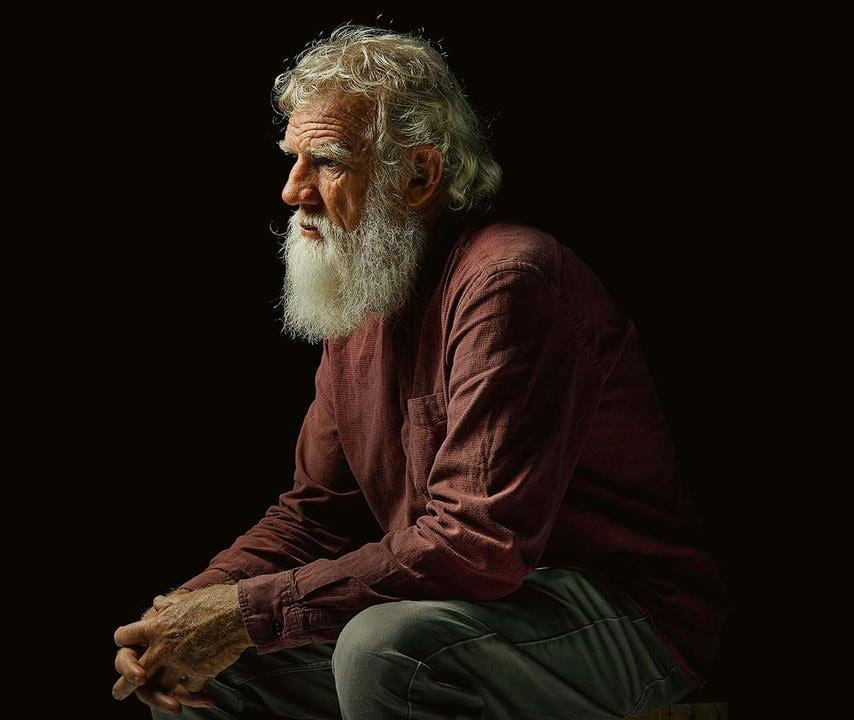

The work of Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu argues for a substantial shift in language from ‘hunter-gatherer’ to terms like ‘farming’ and ‘agriculture’.

Certainly, Indigenous land use has suffered the suggestion of ‘savage’ and ‘primitive’ for too long, but does that justify a shift to Eurocentric language with a particular meaning?

Firstly, the work of Marshall Sahlin from the 1960s [“Notes on the Original Affluent Society” in Lee and DeVore Man the Hunter NY:1968] demonstrated that hunter-gatherer societies were rich, complex and appealing communities, and far from the ‘tooth and claw’ primitive ‘savagery’ of common perception.

In fact, there is good evidence [James Boyce Van Diemen’s Land Black Inc 2008] that early Tasmanian convicts saw the rich possibility of a hunter-gather existence and embraced it – which of course thoroughly annoyed the Establishment. And it is not entirely dissimilar to the white working class “shack culture” of the 19th and 20th century.

Secondly, terms like ‘farming’ involve powerful echoes of John Locke’s dominant Enlightenment concept of Individual Property, which is utterly alien to Indigenous concepts of country which is communal and anything but individual. Further, it was the ‘lack’ of private property and ‘ownership’ in Indigenous culture that ‘excused’ the occupation of land as empty and terra nullius. It may not have been the ‘plough in the soil’ concept of ‘ownership’ but it was nevertheless complex use of country.

We need to be wary of such deeply ingrained western concepts and don’t need to borrow western capitalist concepts to celebrate the Indigenous life world.

That said Rhys Jones’ concept of ‘fire-stick farming’ or mosaic burning [1969 “Fire-stick farming” Australian Natural History 16 (7): 224-228] indicates complex use of fire while using “farming” to indicate a deliberate and sophisticated means of modifying and maintaining landscape by providing continuing pasture for game while at the same time creating nooks, crannies and cul-de-sacs to ease harvesting of game.

This was not wholesale pyromania but very precise firing with very defined lines and margins of cool firing. [Bill Gammage, “Plain Facts: Tasmania under Aboriginal Management” Landscape Research V33, No. 2, April 2008. 241-254]

This was a complex interaction with landscape with precise outcomes that requires constant movement about the Estate [Bill Gammage, The Biggest Estate on Earth 2012] to shape and maintain the landscape.

It required constant movement, a continuous labour of living, but it is not nomadic or random “hunter-gathering”. If that is ‘agriculture’ the term falls short of the incredible scope of landscape maintenance and modification implied by Indigenous practice that centres country in the psyche.

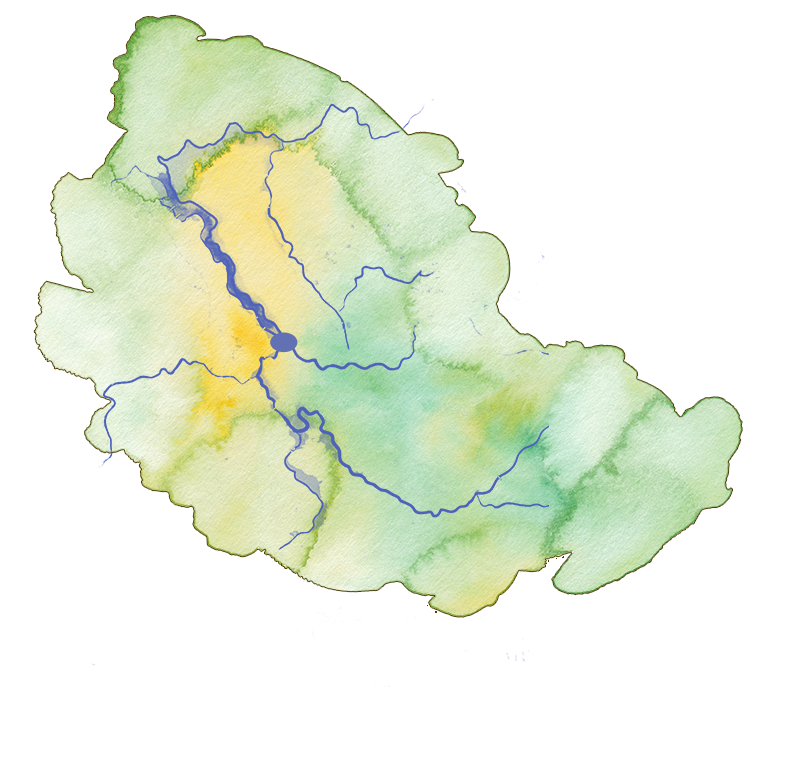

Read More The Launceston Basin

The Geomorphology of the kalamaluka-Tamar Valley

The kalamaluka-Tamar Valley is the product of 200 million years of geological evolution.

The story begins at a time when the old super-continent of Gondwanaland began splitting up, Antarctica was separating from Australia and the Tasman Sea was opening up. Tasmania was very much in the middle of these two movements when the SE part of the Australian continental plate was being stretched both from north to south and from east to west.

Sutton and Dark Emu – Does this amount to ‘farming’ or ‘agriculture’?

Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu has stirred considerable controversy and recent work by Peter Sutton & Keryn Walshe has subject it to critical academic analysis.

Tamar Valley Geology and British Settlement

British settlements, based on the traditions of British farming and shipping, needed arable land and protected anchorages for long-term survival. Well-watered farmland was not to be found easily near the mouth of the Tamar, near York Town or George Town, where the best port facilities were available. In contrast, good port facilities were not to be found at the head of the Tamar where well-watered farmland was available.

The Garden that became Launceston

Rivers wear away the ancient Tasmanian mountains, depositing their mineral wealth in flood plains and estuaries. This depositional richness is most prominent where rivers meet the sea and fine silt drops from the slowing surge. Birds whirl from black gum, paperbark, reed swamp and still water, their nests protruding from the reeds. Some extend their necks to consume the soft aquatic plants that grow in the turbid waters above the mud. Some are eaten by raptors, contact-killed in precipitous descents from above.