A Vast Estate Managed with Purpose

In 2011 Bill Gammage published his controversial, The Biggest Estate of Earth: How the Aborigines made Australia. He refuted the idea of Aborigines as nomadic wanderers idling across the landscape. Instead, he saw the Aborigines as landscape managers, modifying and maintaining a vast Estate, a giant “gentleman’s park.”

The artist John Glover portrayed the Tasmanian Midlands as so unwooded you could “drive a Carriage as easily as in a Gentleman’s park in England” and colonial entrepreneur and dubious shyster, Edward Lord, described driving to Launceston through ‘forest land… very open’ without ‘the necessity of felling a tree’.

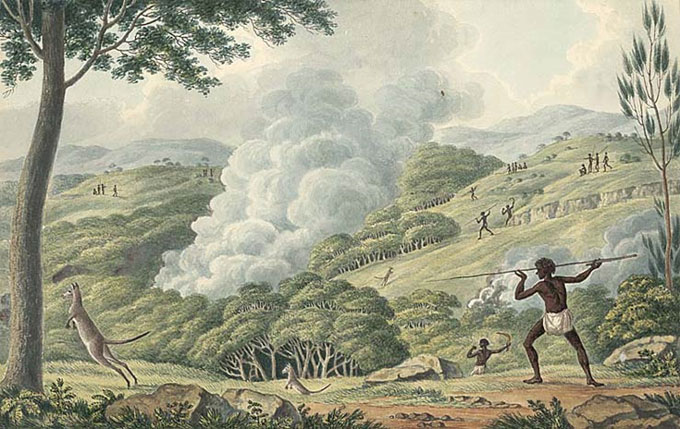

It was sharp edged forest with abrupt edges against grassland, the product of precise cool firing that resulted, as can be seen in Joseph Lycett’s View from Near the Top of Constitution Hill, Van Diemen’s Land 1821 [NGA 84.125.41.]

It can also be seen in Lycett’s Aborigines using Fire to Hunt Kangaroo. [NLA.]

Here Aborigines are using the contours of precisely fired and shaped landscape to drive kangaroo towards hunters.

This view is seriously questioned by Lefroy, Bowman, Williamson& Jones in “New research turns Tasmanian Aboriginal history on its head. The results will help care for the land.” They question ‘this dogma’ of the dependence of Aborigines on open vegetation sustained by frequent burning and suggest it relies on the ‘nostalgic licence of colonial artists’.

They emphasise evidence of artifact scatters which pinpoint Aboriginal occupation to the coastal littoral and the inland waterways like the Tamar estuary.

However, artifact remains are usually concentrated in encampment locations which are always close to freshwater resources – all that is carried when hunting are spears and waddies which leave little artifact evidence. Game that is brought down is brought back to encampments close to fresh water where artifact scrapers and tools are evident in abundance. The evidence of firing, however, remains in the landscape long after. This analysis shows how easily good evidence can affect, even skew, conclusions.

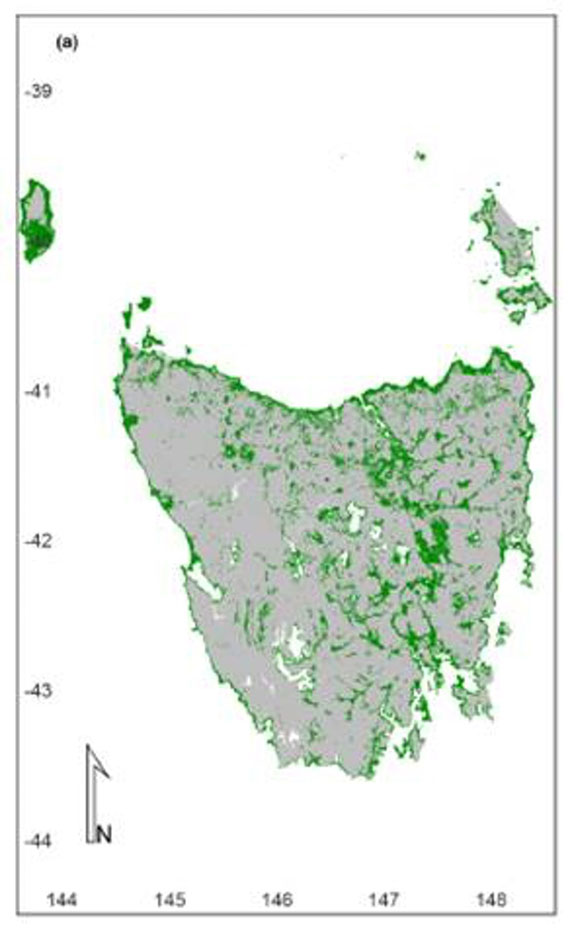

Deadman’s Bay Southwest Tasmania Steve Parish Publishing 2001, from Gammage Greatest Estate, 69.

Gammage’s analysis remains convincing, particularly when viewing Steve Parish’s aerial photo of Tasmania’s SW where the evidence of Aboriginal firing is still clearly obvious in the landscape many years after Aboriginal occupation.

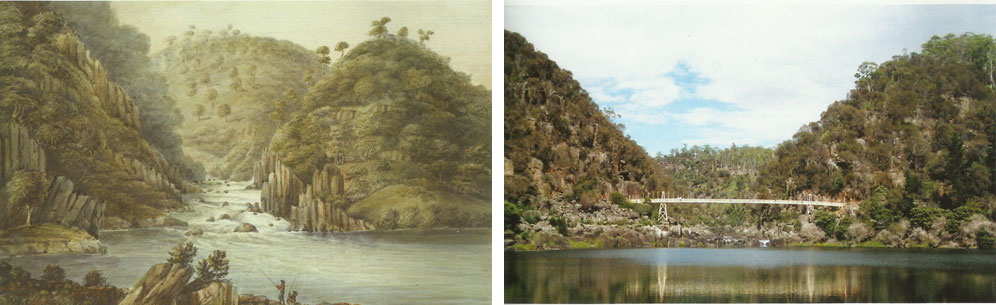

It is more difficult to discern in the Launceston landscape where regrowth obscures the original fired Aboriginal landscape, but contrasted pictures of the Gorge reveals hints of an earlier landscape.

Contrasting images: John William Lewin Cataract on the North Esk near Launceston, 1809 Mitchell Library PXD 388?6 SLNSW. Contrasted with modern photo. From Bill Gammage. The Biggest Estate on Earth 2011, 37.

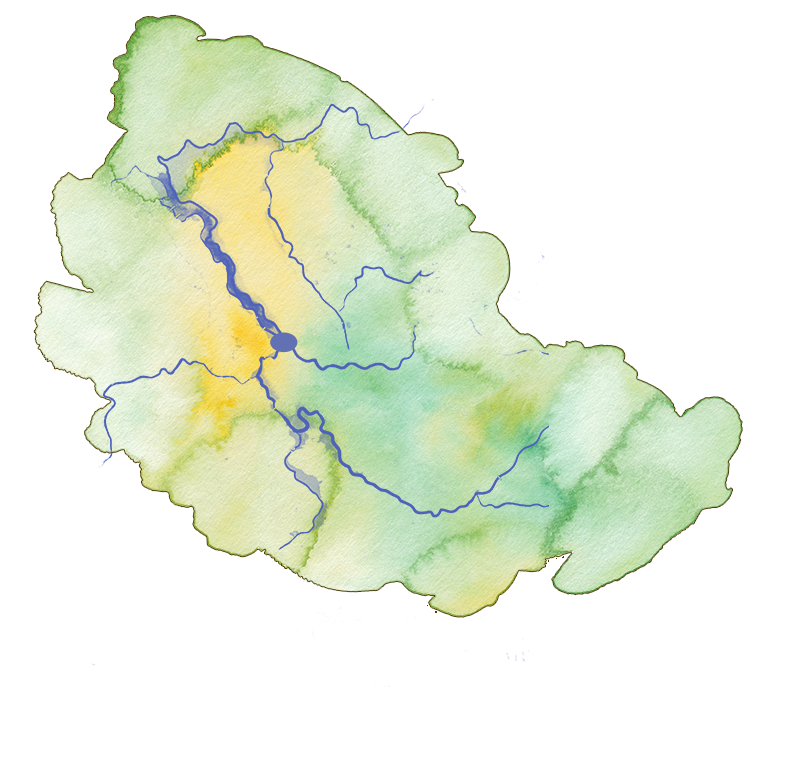

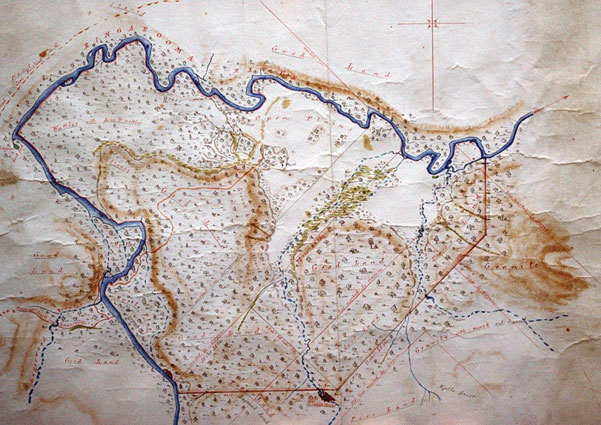

Similarly, in James Scott’s Plan of Braxholm Tasmania 1853, the contours of the Aboriginal fired landscape can still be seen. In fact, it is the ‘good land’ that he describes which are the pastures created by firing, but you will notice the ‘invasion’ of wattle that indicates the long absence of Aboriginal landscape maintenance.

Bill Gammage’s description of Aboriginal landscape management elevates Aboriginal practice from random nomadic wandering and haphazard burning to sophisticated supervision of a vast estate by controlled and precise carving of the landscape along with mosaic burning. Each crafted landscape was made according to needs of the species and vegetation so when people returned to a particular area, they met an abundance. It was like moving from paddock to paddock but leaving sufficient to regenerate for the next time.

James Scott Plan of Braxholm, 1853. (Margaret Newton, Launceston & QVM)

Bruce Pascoe in Dark Emu extends this further to suggest we should discard expressions like ‘hunter-gather’ and instead see Aboriginal land use as a form of ‘farming’ and ‘agriculture’ but that too has many problems.

Certainly, Indigenous land use has suffered the suggestion of ‘savage’ and ‘primitive’ for too long, but does that justify a shift to Eurocentric language with a particular meaning?

Nicholas Petit [Baudin Expedition 1802] Tasmanian Aboriginal canoe [Museum d’Histoire Naturelle, Le Havre]

Read More Envisaging landscape

Is there evidence today of the landscape of the First People?

Actually, there is a lot of evidence if we know how to “read” landscape though intense modification of the Launceston basin makes that more difficult at that location.

This scene from the northeast seems simple enough but it tells a complex story.

What does past practice mean in the present?

The substantial alteration to the landscape by First Peoples does not give permission for us to treat the present landscape as a blank slate to be scribbled on.

White intrusion interrupted Indigenous landscape maintenance by fire and mosaic burning which meant an eruption of fire vulnerable regrowth that cause catastrophic bushfires today.

What would the place have looked like without those First People gathered on the shore?

If you had sailed up the Kunermulukerker, the Tamar, in the wake of the first British interlopers what would the landscape have looked like WITHOUT First People presence and occupancy?

Apart from those riverine margins of vegetation or low rainfall eucalypt forest, the land cover would have been a dominant impenetrable rainforest.

Why multiple names for the river?

Many languages use generic names with adjectival qualifiers e.g “Grey Kangaroo” where “Kangaroo” is the basic word for the animal and “grey” is an adjectival qualifier that broadens our understanding of the basic generic word.

Aboriginal languages tend to use separate, multiple terms instead, so that “grey kangaroo” or “pregnant kangaroo” would be distinct words yet in the understanding of the First People it is assumed we are talking about the same creature with different aspects.