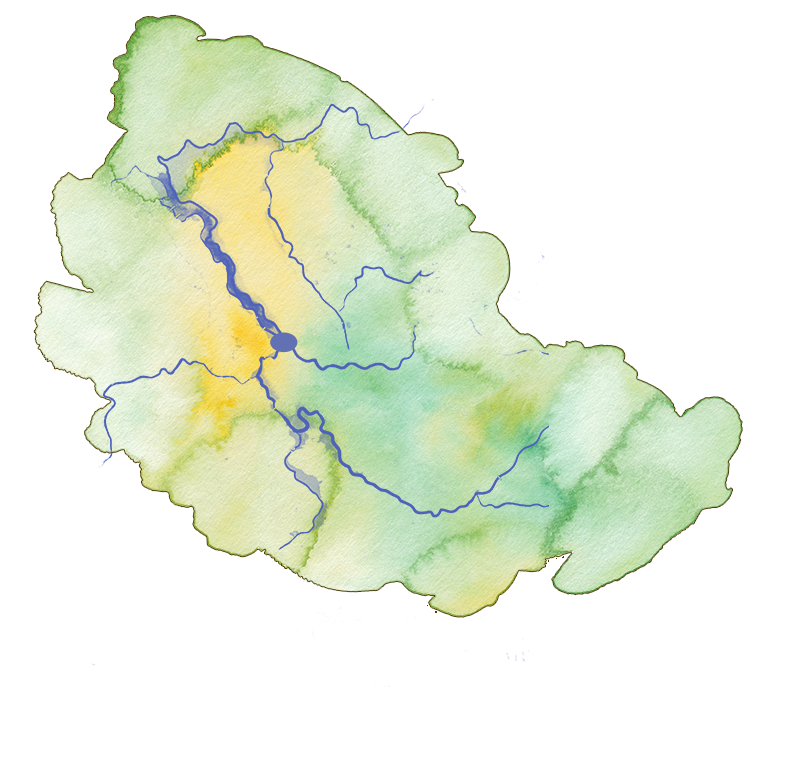

Tamar Valley Geology – Tamar Valley Geology determining occupation.

Ian Pattie.

When William Collins sailed down the waterway now known as the Tamar, in January 1804, he eventually reached and entered a river to the East, the North Esk, and wrote in his logbook:

There are two Arms that lead from the Main head. I proceeded up the first one, taking a south east direction as far as it is projected on the Chart, where the water is perfectly fresh and good. The River here is about Seventy or Eighty yards wide, and has a winding direction towards the junction of the two Ranges of Mountains to the E.S.E. It runs through a low Marshy Country which appears at times to be overflowed. The Soil on its banks is very good, and there is a great extent of it. This part is navigable for a small craft.1

He was describing the delta of the North Esk and the Eastern Highlands beyond and describing conditions that the First People knew about for 39,000 years and would have been utilising as both a water source, food source and pathway.

He then recorded:

On my return I examined the Arm taking a S.W. Direction; upon opening the entrance I observed a large fall of water over Rocks, near a quarter of a Mile up a strait Gully, between perpendicular Rocks about one hundred and fifty feet high; the beauty of the Scene is probably not surpass’d in the World; this great Waterfall or Cataract is most likely one of the greatest sources of the beautiful River, every part of which abounds with Swans, Ducks, and other kinds of Wildfowl.

Collins was awestruck.

His vivid description of the majesty of Cataract Gorge would not have surprised the First People. Natural beauty creates a sense of wonder that is not diminished by an understanding of the forces that created it.

Traversing the Cataract Gorge does not lessen the wonder.

Moving upstream from the entrance to The Gorge, explorers of all eras traverse narrow, rock-walled, short valleys, four natural basins and impressive rock platforms. The Gorge is, and was, a place of wonder and, for the First People, the wonder translated into a place of ceremony.

Aboriginal Elder Patsy Anne Cameron said that The Gorge was a meeting place for storytelling, song, and dance.

The Gorge has a rich well of stories … Landscape tells us our story.

When we say country speaks to us, we mean that certain trees tell us that mutton birds are coming back from their migration, or certain plants that flower tell us that snakes are coming out of their hibernation, the faces of the moon tell us when we’re going to meet somewhere at a certain place, for instance here at the Gorge to dance and conduct ceremonies and exchange information, she said.2

Eleven months after Collin’s encounter with this natural phenomenon, Lieutenant-Colonel William Paterson repeated the trip.

Paterson was despatched from Sydney to establish a gaol-colony at Port Dalrymple and become Lieutenant-Governor of Northern Van Diemen’s Land, following Matthew Flinders’ revelation to the British that VDL was an island separate to mainland Australia. Collins had become Lieutenant-Governor of the Southern part of the colony and there was a fear that the French might establish a colony on the Northern shore of Van Diemen’s Land.

Within days of Paterson’s arrival, on 6 December 1804, he investigated what Collins had called the Main Head and entered the North Esk. He described 43 reaches and passed over four sets of rapids before he abandoned the boats to explore the agricultural potential of the area.

He wrote:

From my Tent there is an extent, which is seen in one View, of nearly three Miles in length, where Thousands of Acres may be ploughed without falling a tree. These Plains extend upwards of ten Miles along the winding Banks, and everywhere equally fertile.3

When he returned to the Tamar, he ventured into the South Esk and reported:

The Entrance into the first fall is picturesque beyond description: the Stupendous Columns of Basaltes on both Sides together with the narrow entrance up to the Cataract, has a very grand appearance, and what made it more so was a number of Black Swans, who could not fly, in the Smooth Water close to the fall; had it not been for the strength of the stream we might have caught every one of them, to the number of about Twenty;3

Whether Paterson knew of Collin’s superlatives or not, his realization of the grandeur of the scene was enhanced by his understanding and appreciation of the geology since he was a scientist and member of the Royal Society. His identification of the “Stupendous Columns” as “Basaltes” was a mistake for the material is dolerite. The mistake appears to have started an almost irresistible and unretractable myth that The Gorge was created by volcanic action.

Geologist, Doug Ewington, said that confusing dolerite with basalt was an easy enough mistake to make but basalt is the result of volcanic action and the myth, that The Gorge was created by volcanic action and the First Basin was a volcanic crater, has persisted.4

Both Collins and Paterson, and other European intruders and surveyors, commented on the abundance of wildlife, and in all cases, this abundance would have been a welcome diet breaker for ships’ crews. This bounty was already known by the First People for whom, in season, collecting wildfowl eggs, meat and feathers would have been a natural consequence of the rhythm of complex hunter-gathering.

Seasonal food, coupled with a place of ceremony, were conditions for bringing people together on a regular basis. It is this realization of seasonal bounty, and gathering to experience the bounty with ceremony, that shows that hunter-gathering was not a serendipitous lifestyle but one of some complexity that the First People created over 39 000 years of occupation.

Paterson’s need was different from Collins. He saw not only beauty and grandeur in the geology but, roundabout, an abundant food source for the gaol builders he needed to feed, while they erected their accommodation and tried to establish a foothold in a new territory.

Further, Paterson’s observations from his trip up the North Esk, that there was open, ploughable country with plenty of water, gave no hint that he understood how it was the land appeared this way.

Matthew Flinders’ revelation that Van Diemen’s Land’s was an island and that there was an extraordinary estuary which had Port Dalrymple at its head, were two of six important geological features that had determined the way in which the First people were able to utilise the land for up to 39 000 years and had been the mainstay of consistent habitation for 23 000 years.

Geologically:

- VDL/Tasmania was an island and had been since the land-bridge to mainland Australia was inundated about 12 000 years ago.

- Volcanic action in the Hillwood area determined the nature of much of the valley.

- The “Main Head” was wholly estuary and was fed, principally, by two large rivers but several smaller rivers and creeks.

- There was easy access to significant grasslands with few trees along the whole estuary and via one of the rivers.

- The entrance of another river presented majestic rock formations.

- Rapids were features of both rivers.

The First People entered a landscape already sculpted by millions of years of volcanic action, glaciation, huge lake development and the laying down of scores of metres of sediment.

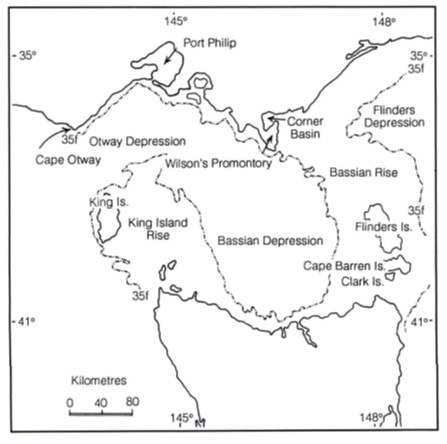

The pre-separation map below, shows the Bassian Rise wherein lay the land bridge and the future islands – Flinders, Cape Barren, Clark and others – and on the opposite side of the Bassian Depression, in the King Island Rise, future islands – King, Three Hummock and others.

The Bassian Rise, the land-bridge from Tasmania to mainland Australia, has the Peak, Mt Strezlecki, 756m above the ocean, the deepest point of which is 70m meaning that the First People, 39,000 years ago, had the prospect of an 800+metre trek from the highest to the lowest point. The decision to take the trek from the land-bridge to the floor of the Bassian Depression, would have depended on what was hoped to be gained in food, water, and ceremony.

Ewington said that the creation of the island occurred during the last of three great episodes of glaciation, 75,000 – 12,000 yearsago, but the major upheavals that gave the land its significant and determining features occurred about 70-80 million years ago. 5

In his 2008 paper, Formation of the Cataract Gorge, Ewington wrote:

The creation of major fault valleys (grabens), three of which are the Port Sorell, Tamar and Boobyalla grabens gave us a recognisable landscape, with the Western Tiers to the south-west of Launceston and the range of dolerite-capped hills and mountains from Mt George to the Ben Lomond massif East of the Tamar graben.

The major fractures which formed the grabens were in two sets. The most major run away to the north – north-west, while the lesser set runs roughly at right angles to the major set. …

This gave us the foundations of today’s topography and landscape, developed by the Tamar-Esk river system.

The final melting of the ice on Tasmania’s mountains began about 20 000 years ago, and sea level was finally established at its current level, somewhere between ten thousand and seven thousand years before [the] present. 4

Antecedents of the First People were increasingly constrained by the geological evolution and witnessed episodes of the transformation.

The major features of Bass Strait, oriented along NW-SE and NE-SW lines 9

The map indicates that it took about 1000 years to complete the isolation of Tasmania; 13000 years ago, a tiny land-bridge remained: bathymetry data sources.

The feature which dominates the Launceston landscape is the opposing Esk river systems, almost at right angles, that, in flood time, crash into each other and which, through their power, have created a large, fertile floodplain.

It was not always thus.

The North and South Esks originate within 10km of each other on Mt Ben Lomond and taking northerly and southerly routes, drain about 25% of the Tasmanian landmass and deliver the waters into the Tamar Valley.

A volcano in the Hillwood – Batman Bridge area about 30 million years ago, dammed the Tamar and created a freshwater lake stretching from Whirlpool Reach to Longford, and up to 5km wide in places.

Ewington added:

After some ten million years or so, the Tamar managed to cut through the volcanic barrier which had formed the lake, and it drained away. The river system rapidly eroded the lake sediments, carving out a new landscape.5

The North Esk is still in the same location but the South Esk ran, more-or-less, down where Wellington Street is today and the erosive power of the combined waterways, coupled with the lower sea level, meant that 30 million-years ago the Tamar had huge potential to transform the land as it flowed through the former lake, across the Bassian Plain and into the sea near King Island.

Millions of years later, remnants of the South Esk’s Wellington Street route would have been seen by the First People and the English soldiers, convicts and settlers in Glen Dhu Creek which flowed to the Tamar and the Kings Meadows Rivulet, and thereafter into the North Esk. Glen Dhu Creek, flowing approximately down Margaret Street, and entering the Tamar Basin in any spot west of the Ritchies Mill rock outcrop, accommodated enough tidal water to float barges up to the Margaret Street Brickfields. The huge clay resource of the Margaret-Wellington Street ridge, used by early brickmakers, was laid down by the huge Lake Tamar.

The debate about how the South Esk finally flowed through Cataract Gorge, creating today’s the well-known spectacle, is a debate about which is the major river, and which is the tributary.

Ewington said:

I believe that approximately 15 million years ago the South Esk, somewhere between Western Junction and Evandale, struck solid rock in the form of the lava flow which underlays the runway of Launceston Airport and is exposed in the quarries south and southwest of there, and changed course.

Rivers are ‘lazy’ and seek the easiest way to the sea. To avoid the basalt and dolerite north of Evandale, the South Esk swung westward and flowed across the flat ground, underlain by relatively soft rocks, until it encountered the Lake River near today’s Longford.

This greatly enlarged stream then flowed into the Meander and thus down the Gorge. Today we see the Meander and Lake as tributaries of the South Esk, but this wasn’t always the case.5

The nature of river action through basalt is to dig deep and create steep-sided gorges, hence, Cataract Gorge.

Also, according to Ewington, and often stated in discussions on siltation of the Tamar Basin, the North Esk’s conjunction with the Tamar is about as far South now as it has ever been in the last 12,000 years.

This means that different generations of the First People would have been able to watch the North Esk charge its way into the Tamar at points as far North as the Mowbray Hill and its present outfall. The people would have watched as frequent floods flowed over and through the North Esk delta and, at different times, break through the sedimentation at several spots but never eroding the hill on which sits the Invermay Primary School.

Therefore, when Flinders, Collins, Paterson et al sailed into the estuary they sighted land on both sides that had, over millions of years, been sculpted by upheavals and a great lake laying down sediments and, eventually, productive soils that had, for thousands of years been the maternal resource of an ancient people.

Further, William Paterson did not know, or had not yet realized, despite the time he had already spent in New South Wales, that the North Esk land, with its “thousands of acres [that may] be ploughed without falling a tree”, were further changed by the combined result of First People land management and ”the biological attributes of the eucalypt forests, and the natural successional processes within them.”6

This double-barrelled explanation by Ross Florence,

- Firestick land management; and

- The natural attributes of eucalypts

would have been contested by Prof. Bill Jackson, who, according to Prof. Rhys Jones, said that you could only explain the floristic diversity of Western Tasmania through one factor, the frequency and intensity of fire.7

He also said that in his opinion this was not just a natural regime, but that what we were looking at in Western Tasmania, was a legacy of a major impact of fire-induced vegetational diversity.7

Rhys Jones cited the George Augustus Robinson journals of 1829 -1932. Robinson revealed that the landscape of Western and North-western Tasmania was composed of areas of “open sedge-lands” and “little groves separated by open country [and the Aborigines] not only applied the fire to open country but they also tried to put the fire out as it got close to the groves.”7

By extension of both Robinson and Jackson’s words, and because of interaction between First People clans, the same effect would have been seen in the huge Tamar Valley and its hinterlands to the West and East just as Paterson observed.

The records of other settlers revealed that the firestick practice had to be regular and consistent, because the Tasmania flora had a rapid rebuff for inconsistency.

In 1840-1850, wrote Rhys Jones, “poet and ecologist” Mrs Louise Meredith said that the Aborigines had ceased burning in Eastern Tasmania and in 30 years a great change had come about in the countryside. Of the former open parkland appearance of the area, she said to her husband Charles:

This looked like a great romantic English scene, like a great park with these trees and open country. Terrific! And now look at it! Terrible bloody stuff! Thick bush everywhere and these terrible fires coming through every now and then.7

The 30-year observation of the rapid return to thicket from open grassland, not only showed the need for consistent burning to achieve the parkland appearance, but also indicated the need for a burning regime if the First People were to manage the flora and fauna resource they inherited.

Firestick land management was customary amongst the Australia’s First People and evolved into burning with ceremony.

John J. Bradley, in his paper Fire: emotion and politics8 said, “Fire is one event which is related to many others,” and here he was talking about the ceremony and regulations that accompanied the firing of different parts of the country. His is a Northern Australia experience, but relevant, and he adds that burning the country “is a social and cultural power as well as a biological and physical power” unlike the “European-origin culture where smoke seen in the distance or the lighting of fire is seen as a signal of distress.” To the First People “smoke from the country that is burning tells the observer that everything is good, the people on the land are well, and doing what is required of them.”8

The emotion of which he speaks relates to:

- There are at least 10 Yanyuwa words for fire and smoke.

- a demonstration of continuity with the ancestors.

- practice that does not offend the spirits.

- a right to the land – ownership through utilisation.

- When the flora indicates that the land is right for burning, permission from the “owner” must be sought.

- Respect for country that has ancestral spirits or is a burial ground has rules for timely burning.

William Collins and William Paterson, without having the luxury of Robinson’s years of residence with observation, recorded what the First People already knew: the Tamar Valley was a beautiful area with an abundant food source, but what was more disconcerting for the First People, it was an area able to support Northern Hemisphere farming practices.

From Robinson’s observations of firestick practice it is inferred that at some time in the 39 000 years of human habitation in Tasmania and the 23 000 years of consistent habitation, the First People might have looked down from the higher levels of the land onto the Bassian Depression and seen areas of open grassland that had been fired amongst whatever woody vegetation would survive in a cold climate.

The people would also have been able to see the combined waters of the North and South Esks winding its way across the Bassian Plain to flow into the ocean near King Island.

With the rise of Bass Strait, the waterways, more and more affected by estuarine water, entered the long-term flocculation process which continues today. Salty water causes silt particles to clump and settle creating the huge resource known as the North Esk delta and the Tamar mud flats.

Plants regrowing in rich silt, attracting bird and other animal life, would have created a pattern of lifestyle with ceremony for the First People as they followed paths from wetlands to drylands for the seasonal bounty.

The North Esk is not the only waterway in the Tamar region to create a delta, but it is the most significant.

In this region, where three First People Clans intersected, the forces of nature sculpted the land, organic elements created the living diversity, the First People evolved a relationship with the environment and the First Europeans exploited their happenstance.

The North Esk confluence with the Tamar shows Royal Park, unformed, and still part of the flood plain long after Launceston was a thriving settlement.

Bibliography

- Low Head to Launceston: The Earliest Reports of Port Dalrymple and the Tamar, by C. C. Macknight; William Collins: Report of a Survey of the Harbour of Port Dalrymple, January 1804, Historical Survey of Northern Tasmania 3, Launceston, 1998

- Patsy Cameron reveals the deep history of the Gorge, Piia Wirsu, The Launceston Examiner Newspaper, 25 June 2017

- Low Head to Launceston: The Earliest Reports of Port Dalrymple and the Tamar, by C. C. Macknight; Chapter 4, Paterson, November and December 1804, Historical Survey of Northern Tasmania 3, Launceston, 1998

- Formation of the Cataract Gorge, Doug Ewington, 2008, paper held in the QVM&AG

- Launceston Geology and Origin of the Punchbowl, Ian Pattie, Excerpts from articles by Doug Ewington, 2008, held in the QVMAG.

- “The Ecological Basis of Forest Fire Management in New South Wales,” Ross G. Florence, The Burning Continent – Forest Ecosystems and Fire management in Australia, Institute of Public Affairs, Sept. 1994. Florence cites G.N. Park, Nutrient dynamics and secondary ecosystem management,D. thesis, ANU, 1975

- Mindjongork- Legacy of the firestick, Rhys Jones, Country in Flames, Proceedings of the 1994 Symposium on biodiversity and fire in North Australia, 12; D.B. Rose (ed), Biodiversity Series, Paper No. 3, Biodiversity Unit, Dept of the Environment, Sport and Territories, and the North Australia Research Unit, The Australian National University, 1995

- Fire: emotion and politics, A Yanyuwa case study; John J. Bradley, Faculty of Arts, NTU, in Country in Flames , Proceedings of the 1994 Symposium on biodiversity and fire in North Australia, 25-31; D.B. Rose (ed), Biodiversity Series, Paper No. 3, Biodiversity Unit, Dept of the Environment, Sport and Territories, and the North Australia Research Unit, The Australian National University, 1995

- Behind the Scenery Tasmania’s Landforms and Geology, Scanlon, Fish and Yaxley, p 95, Department of Education and the Arts, Tasmania, Australia 1990

Read More The Launceston Basin

The Geomorphology of the kalamaluka-Tamar Valley

The kalamaluka-Tamar Valley is the product of 200 million years of geological evolution.

The story begins at a time when the old super-continent of Gondwanaland began splitting up, Antarctica was separating from Australia and the Tasman Sea was opening up. Tasmania was very much in the middle of these two movements when the SE part of the Australian continental plate was being stretched both from north to south and from east to west.

Sutton and Dark Emu – Does this amount to ‘farming’ or ‘agriculture’?

Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu has stirred considerable controversy and recent work by Peter Sutton & Keryn Walshe has subject it to critical academic analysis.

Tamar Valley Geology and British Settlement

British settlements, based on the traditions of British farming and shipping, needed arable land and protected anchorages for long-term survival. Well-watered farmland was not to be found easily near the mouth of the Tamar, near York Town or George Town, where the best port facilities were available. In contrast, good port facilities were not to be found at the head of the Tamar where well-watered farmland was available.

The Garden that became Launceston

Rivers wear away the ancient Tasmanian mountains, depositing their mineral wealth in flood plains and estuaries. This depositional richness is most prominent where rivers meet the sea and fine silt drops from the slowing surge. Birds whirl from black gum, paperbark, reed swamp and still water, their nests protruding from the reeds. Some extend their necks to consume the soft aquatic plants that grow in the turbid waters above the mud. Some are eaten by raptors, contact-killed in precipitous descents from above.

Does this amount to ‘farming’ or ‘agriculture’?

The work of Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu argues for a substantial shift in language from ‘hunter-gatherer’ to terms like ‘farming’ and ‘agriculture’.

Certainly, Indigenous land use has suffered the suggestion of ‘savage’ and ‘primitive’ for too long, but does that justify a shift to Eurocentric language with a particular meaning?