The Garden that became Launceston

Jamie Kirkpatrick

School of Geography, Planning and Spatial Sciences, University of Tasmania

Rivers wear away the ancient Tasmanian mountains, depositing their mineral wealth in flood plains and estuaries. This depositional richness is most prominent where rivers meet the sea and fine silt drops from the slowing surge. Birds whirl from black gum, paperbark, reed swamp and still water, their nests protruding from the reeds. Some extend their necks to consume the soft aquatic plants that grow in the turbid waters above the mud. Some are eaten by raptors, contact-killed in precipitous descents from above. The eggs and flesh of others are eaten by the people who hunt, gather and cultivate the best of the wealth of life in the places in which it is most manifest. People hunt the kangaroos, wallabies, pademelons and wombats who are also attracted to the rich wetlands. These mammals are also killed or scavenged by thylacine, devil and quoll. People harvest tubers of wetland plants, making sure that they ensure that they can do the same in the future. They eat shellfish from the rivers. They burn parts of swamps when dry to help maintain food production. They do not feel separate from the rest of the world.

Joseph Lycettt (1774-1828) View Upon the South Esk River. Art Gallery of South Australia

Papers and Proceedings of the Royal Society of Tasmania, Volume 123, 1989 229

THE CONSERVATION OF ORIGINAL VEGETATION REMNANTS

IN THE MIDLANDS, TASMANIA

by R, J, Fensham and J. B. Kirkpatrick

The Pre-European Vegetation of the Midlands, Tasmania: A Floristic and Historical Analysis of Vegetation Patterns R. J. Fensham: Journal of Biogeography, Vol. 16, No. 1 (Jan., 1989), 29-45

The wetlands at the head of the Tamar Estuary covered a much larger area than they do today, with much of them now drained or filled under suburbia, box stores, hotels, sports fields and university, only rarely reclaimed by extreme floods.

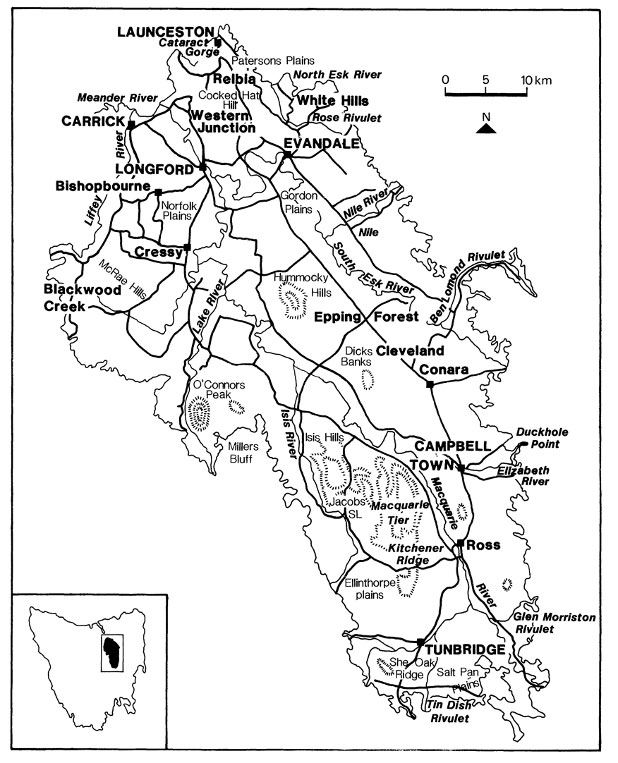

To the south of the North Esk River above the flood line on fertile soils on gentle slopes, scattered umbrella-like giant black gums and white gums decorate tussock grassland and red green swards of kangaroo grass. This parkland is heavily grazed by marsupials to the degree that people do not need to burn it in most years. Marsupial lawns are difficult to burn at the most fire hazardous of times. Burning, digging and grazing maintain habitat complexity in these grasslands and grassy woodlands, which, without these disturbances, lose many of the species that humans and other mammals use for sustenance. People eat the tubers of orchids and herbs, make flour out of grass and wattle seeds, eat seasonal fruits, like those of the native cranberry, climb trees to kill the occasional possum for grilling, hunt emus, kangaroos and wallabies, and build huts, fires and fire shelters close to clear fresh water.

This type of country is now totally built over in Launceston. Small patches have survived agricultural development in remote valleys in the Midlands.

A person digging tubers in a swamp adjacent to the North Esk River could look south through the grassy woodland to see black peppermint forest on the sedimentary deposits of the rise. This forest is not devoid of resources for humans and other mammals but is not as rich as wetland and woodland. Potoroos, pademelons, bandicoots and bettongs like the occasional dense shelter in these forests. Some of the smaller of them feed on fungal hyphae, which in turn feed on the trees, causing lines of excavations along roots. Pademelons graze and browse, consuming plants that are toxic to most other mammals. Ring-tailed and brush-tailed possums frequent the trees. Orchids and lilies are profuse in spring in the often-sparse ground stratum. People patch burn the forest, creating a mosaic of dense shelter and open feeding grounds for the mammals they consume and allowing sunlight to nurture the growth of edible bulbs and tubers.

This type of country survives in the remnants of Epping Forest in the northern Midlands, where some of the reserves also have small patches of woodland, grassland and wetland.

If the digger of the tubers looks to the west, they see a gorge debouching the South Esk River and rocky slopes with scattered eucalypts, sheoaks, cherries, honeysuckles and other small trees. These woodlands of the dolerite slopes were managed by people to maintain their openness, as well as to create occasional dense copses to shelter macropods during the day.

The White Hills near Evandale are now black with invading eucalypts and wattles under post-invasion management regimes. The country around the Gorge is much thicker with trees than before the invasion, although the thickest patches, dry rainforest dominated by native olive, are almost certainly unchanged.

Read More The Launceston Basin

The Geomorphology of the kalamaluka-Tamar Valley

The kalamaluka-Tamar Valley is the product of 200 million years of geological evolution.

The story begins at a time when the old super-continent of Gondwanaland began splitting up, Antarctica was separating from Australia and the Tasman Sea was opening up. Tasmania was very much in the middle of these two movements when the SE part of the Australian continental plate was being stretched both from north to south and from east to west.

Sutton and Dark Emu – Does this amount to ‘farming’ or ‘agriculture’?

Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu has stirred considerable controversy and recent work by Peter Sutton & Keryn Walshe has subject it to critical academic analysis.

Tamar Valley Geology and British Settlement

British settlements, based on the traditions of British farming and shipping, needed arable land and protected anchorages for long-term survival. Well-watered farmland was not to be found easily near the mouth of the Tamar, near York Town or George Town, where the best port facilities were available. In contrast, good port facilities were not to be found at the head of the Tamar where well-watered farmland was available.

Does this amount to ‘farming’ or ‘agriculture’?

The work of Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu argues for a substantial shift in language from ‘hunter-gatherer’ to terms like ‘farming’ and ‘agriculture’.

Certainly, Indigenous land use has suffered the suggestion of ‘savage’ and ‘primitive’ for too long, but does that justify a shift to Eurocentric language with a particular meaning?