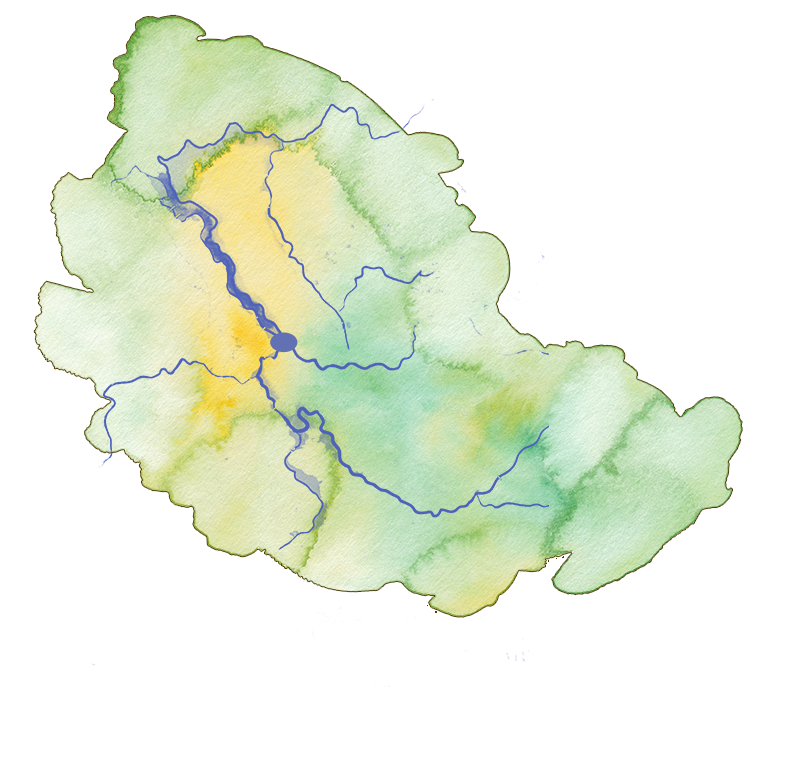

The Geomorphology of the kalamaluka-Tamar Valley

Tom Dunning

Formation of the Tamar Graben

The kalamaluka-Tamar Valley is the product of 200 million years of geological evolution.

The story begins at a time when the old super-continent of Gondwanaland began splitting up, Antarctica was separating from Australia and the Tasman Sea was opening up. Tasmania was very much in the middle of these two movements when the SE part of the Australian continental plate was being stretched both from north to south and from east to west.

About 180 million years ago, at the beginning of the Jurassic Period, the tensions created by these movements allowed lava to intrude through weaknesses in the crust and spread out below what are now the central, western and southern parts of Tasmania. It cooled slowly, well below the surface, to form a very hard rock called dolerite. Over the next 80 to 90 million years the rocks above the dolerite were gradually worn away until it was left as a hard erosion-resistant cap, which tops many of Tasmania’s mountains today. To the east and west of the dolerite were the older rocks which still form the north east and western parts of Tasmania, including the Narawntapu Mountains.

From 95 to 65 million years ago the splitting of the Australian continent from Antarctica created a series of earth movements. There was a rapid uplift of Tasmania by some 1000 metres. Then earthquakes began to split up the dolerite capped plateau, creating a trough. This graben, stretched from central Bass Strait through central northern Tasmania into the Midlands, with high plateaux or horsts on either side. These are today the Western Tiers, and the Eastern Tiers of Ben Lomond, Mt Barrow and Mt Arthur.

The central trough was split into two main valleys, separated by a central horst. The rivers draining the mountains flowed into the valleys, creating two huge lakes, stretching from near Tunbridge out into Bass Strait, all of which was above sea level. Tasmanian geologist Samuel Carey named them Lake Tamar, which occupied the present valley of the South Esk and Tamar rivers, and Lake Cressy, which occupied the Norfolk Plains and entered the Bass Basin between Devonport and Port Sorell.

For the next 10 million years streams eroding the highland areas flowed into the lakes and deposited their sediments, filling the two lakes with clay, sands, gravel and boulders to a depth of up to 800 metres. About 47 million years ago these lakes were breached and drained, to create the Midland and Norfolk Plains.

The central horst is represented by the Hummocky Hills, near Epping Forest, Mount Arnon and the Devon Hills north of Perth and Longford, and the dolerite escarpment of the West Tamar. It was not continuous. There were areas where the two lakes joined and sediments completely buried the horst.

Today the Midland Plain stretches as far north as Evandale, Perth, Longford and Hadspen. Originally the plain stretched much further north down the Kalamaluka-Tamar Valley, and from west of Westbury to Port Sorell and beyond.

With the disappearance of the lakes, the South Esk River now drained the eastern side of the graben, while the Lake and Meander rivers drained the western side. Today the Midland Plain stretches as far north as Evandale, Perth, Longford and Hadspen. Originally it reached the graben much further north, down the kalamaluka-Tamar Valley and from west of Westbury to Port Sorell and beyond.

For the next 8 million years The South Esk River eroded down into the lake sediments, creating a deeper valley. The sediments were not consolidated into hard rock and much of it was clay. Undermining the slopes was easy and the river carried the debris downstream and out into the Bass Basin, which was well above sea level.

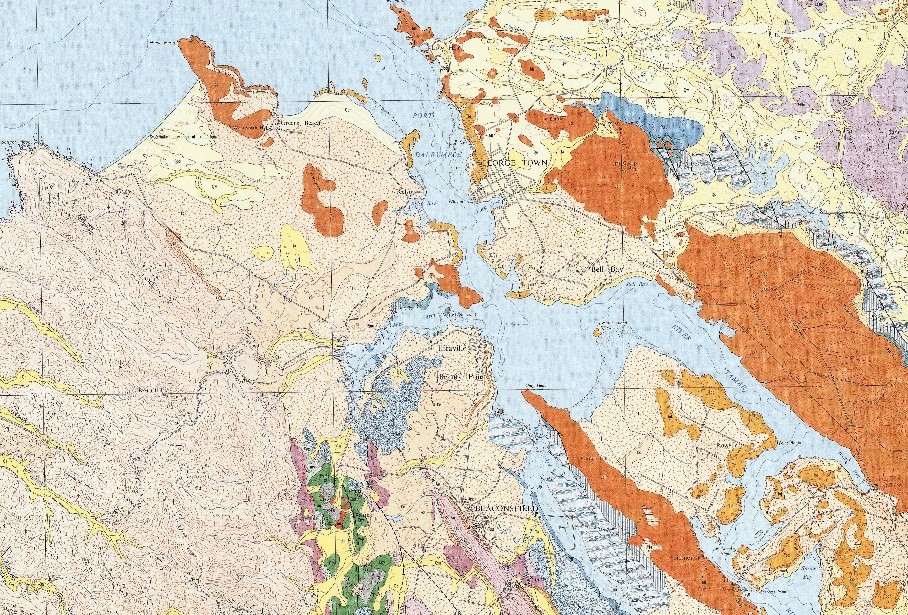

19 Geological map of the lower kalamalanka Tamar Vslley. The river divides the old sediments into separate segments Eastern Arm, Rowella, Bell Bay – George Town, Beauty Point – Kelso .Basalt flows have been incorporated into the sedi-ments, protecting them from erosion. The Eearth’s crust has sagged under the weight of the sediments. The dolerite hills become lower, then are buried in the sediments.

20 East Arm and Rowella Peninsulas, divided by the Kanamaluka-Tamar River, Bell Bay in the distance.

Basalt within the sediment layers and lining the foreshore protect these peninsulas from erosion.

21 Beauty Point Western Arm and the Narawntapu Range from Mount George

MiddleArm and Western Arm lie outside the Midland Valley. Their sediments were probably caused by a breaching of the western horst by Lake Launceston. At some stage the river entered the Bass Basin west of West Head, This may have been caused by basalt blocking the course of the river between South George Town and Clarence Point. The Narawntapu Range is part of an older geological system.

Read More The Launceston Basin

Sutton and Dark Emu – Does this amount to ‘farming’ or ‘agriculture’?

Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu has stirred considerable controversy and recent work by Peter Sutton & Keryn Walshe has subject it to critical academic analysis.

Tamar Valley Geology and British Settlement

British settlements, based on the traditions of British farming and shipping, needed arable land and protected anchorages for long-term survival. Well-watered farmland was not to be found easily near the mouth of the Tamar, near York Town or George Town, where the best port facilities were available. In contrast, good port facilities were not to be found at the head of the Tamar where well-watered farmland was available.

The Garden that became Launceston

Rivers wear away the ancient Tasmanian mountains, depositing their mineral wealth in flood plains and estuaries. This depositional richness is most prominent where rivers meet the sea and fine silt drops from the slowing surge. Birds whirl from black gum, paperbark, reed swamp and still water, their nests protruding from the reeds. Some extend their necks to consume the soft aquatic plants that grow in the turbid waters above the mud. Some are eaten by raptors, contact-killed in precipitous descents from above.

Does this amount to ‘farming’ or ‘agriculture’?

The work of Bruce Pascoe’s Dark Emu argues for a substantial shift in language from ‘hunter-gatherer’ to terms like ‘farming’ and ‘agriculture’.

Certainly, Indigenous land use has suffered the suggestion of ‘savage’ and ‘primitive’ for too long, but does that justify a shift to Eurocentric language with a particular meaning?