An Encounter with the First People of Northern Van Diemen’s Land

1642 – 1812, Tasman to the end of the First Epoch

Ian Pattie, July 2021

Abstract

Dutch, French, and British explorers set foot in Van Diemen’s Land from 1642 bringing with them a range of preconceptions and prejudices about what and who they might find.

Geographically, the European expectation was for a landmass, equal to, or balancing the landmass of the Northern Hemisphere, hence the search for “The Great South Land”.

Anthropologically, the European explorers anticipated finding natives like those they had encountered in Africa and the Pacific Islands. The expectation of similarity extended to colour, cultural traditions and even sexuality. They had to discover if the people were indeed black, tall in stature, woolly-haired, sexually adventurous or of a warrior disposition.

Politically, some of the explorers came for trade, some for scientific curiosity and what might develop from it, and others for acquiring land in the name of their ruler. Behind all these purposes was empire building.

The original encounters with the First People of Van Diemen’s Land were full of surprises including that the people were not as black as Europeans expected them to be, nor were they to be submissive.

The Dutch, apart from one man, never landed on the shores of Van Diemen’s Land but significant numbers of French and British explorers did, bringing with them European diseases, which had devastating effects upon the First People, from whose viewpoint, the British also brought unacceptable and regard for the land and its utility.

This summary of the first encounters by Dutch, French and British explorers, and eventually British settlers, is Euro-centric. It collects the prejudices and impressions of Europeans as they encountered the First People of the Dutch-named Van Diemen’s Land and the British-named New South Wales.

The summary admits that none of the first European visitors to Van Diemen’s Land described the island as unoccupied. It is hypothesized, therefore, that all the visiting personnel would have been taken aback by Governor Bourke’s 1835 proclamation of Terra nullius – that the land “belonged” to no one prior to British claiming possession in 1770. The proclamation of Terra nullius was made almost 200 years after Abel Janszoon Tasman came to an occupied island; he called Van Diemen’s Land.

An encounter with the First People of Van Diemen’s Land 1642 – 1812 is in three parts:

- 1642 – 1793, Tasman to Hayes

- 1798 – 1804, Flinders to Paterson

- 1804 – 1812, Paterson to Ritchie and the End of the First Epoch.

The term, First Epoch, was used by Frederick Watson, editor of the Historical Record of Australia to describe the period of British occupation to 1812 and this, in the main, is the limitation of the record of the first encounters between the European explorers and the First People of the island.

Read More Understanding how First People’s viewed their world

An Encyclopedia of Tasmanian Aboriginal Anthropology

On the 18th February 1802 the Botanist, Leschenault, of the French exploration expedition led by Nicholas Baudin while at Maria Island, came across a small mound with a tent like “wigwam” of bark over it.

FOOD FORAGING (PART 2 “FORAGING & FOOD PREPARATION”)

Hunting by men was often one of a fortuitous meeting a quarry and resulted in a lack of success having to return to camp empty handed, but not to worry, the ever-reliable women filled the void with smaller fauna, possum and edible flora.

FOOD FORAGING (PART 1 FOOD RESOURCES 2,000 > BP)

The Tasmanian Aborigines occupied their island home for at least 40,000 years but it is only the last 2,000 years that is considered here and only mainland Tasmania and offshore islands.

An Encounter with the First People of Northern Van Diemen’s Land A Particularistic Mindset

When Lieutenant-Colonel William Paterson brought a group of white settlers – soldiers, convicts, and farmers – to Port Dalrymple, Van Diemen’s Land, the English were in a mindset of domination or mastery over other races.

Britain was the world’s naval power, the coming industrial power, the greatest empire builders and affectionately described amongst themselves as the chosen people and the Protestant Protectors.

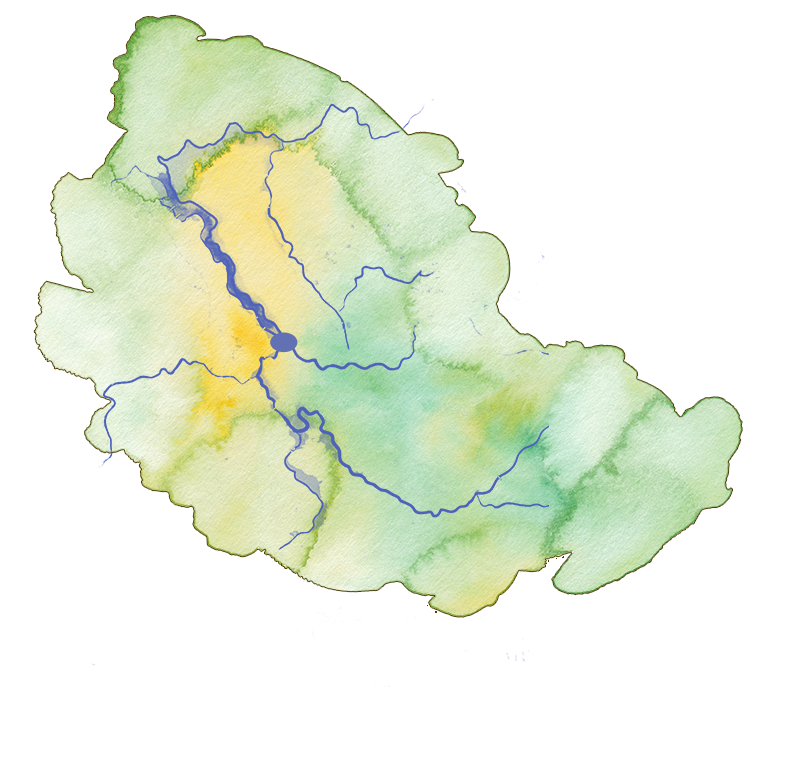

Tamar Valley Geology Determining the First Peoples Occupation of Northern Van Diemen’s Land

When William Collins sailed down the waterway now known as the Tamar, but which he called the Main Head in January 1804, he eventually reached and entered an Arm to the East, the North Esk, and wrote in his logbook1 that “the water is perfectly fresh and good”, it flowed over a flood plain and “the Soil on its banks is very good and there is a great extent of it.”

An Encounter with the First People of Northern Van Diemen’s Land

When William Collins sailed down the waterway now known as the Tamar, in January 1804, he eventually reached and entered a river to the East, the North Esk, and wrote in his logbook.

Adequacy

It is tempting to apply modern terms like ‘sustainability’ to Indigenous practice however the key to understanding First People’s attachment to country is adequacy.

First Peoples did not expend energy on wasted accumulation but on a vast Estate that provided the needs of a robust population using minimal exertion. “It depended on preferring to reduce rather than increase material wants.”

A “grounded” rather than “portable” faith – A Psychic Invasion.

Europeans have always had difficulty in grasping a concept of religion in Indigenous practice and even denied until the mid 20th century that you could apply the term ‘religion’ to Aboriginal practice – magic and sorcery but not ‘religion’.

Tamar Valley Geology determining occupation

When William Collins sailed down the waterway now known as the Tamar, in January 1804, he eventually reached and entered a river to the East, the North Esk, and wrote in his logbook.