Tamar Valley Geology and British Settlement

Addendum: to Tamar Valley Geology Determining the First Peoples Occupation of Northern Van Diemen’s Land

Addendum: to Tamar Valley Geology Determining the First Peoples Occupation of Northern Van Diemen’s Land

Abstract

The British decision to settle at the head of the Tamar Estuary opened a battle with the Tamar Valley’s geology and the forces of nature that surround it. The British desired to impose its will on the environment and the First People. The British administration did not enter Van Diemen’s Land with a sense of adapting to its delimitations. The geological and biological foundations for human existence in Van Diemen’s Land, did not create a Biblical Eden, but rather a landscape which might be adapted to human needs. The First People’s firestick technology was just one form of adaptation, but British settlement – the transference of a European island lifestyle to the Southern Hemisphere – required an attempt at domination of the environment. In this attempt, the British were overlaying their experience, culture and needs on the same ground that had sustained the First People’s experience, culture and needs. The attempt started immediately the British landed and continues today, although accommodation, not domination has been the realization.

The British settlers brought with them the knowledge of a thousand years of living in, and adapting, swampland to their needs. If they were to make a permanent settlement, they needed to control the swampland that made the North Esk River delta, and the first solution was to stop the area flooding at high tide, and this required a tidal levee.

This addendum to Tamar Valley Geology Determining the First Peoples Occupation of Northern Van Diemen’s Land, takes a brief look beyond the first few years of British settlement and the battle to survive and on the North Esk River floodplain. The events occurred within a 300m radius of where the British first stepped ashore in the North Esk Estuary.

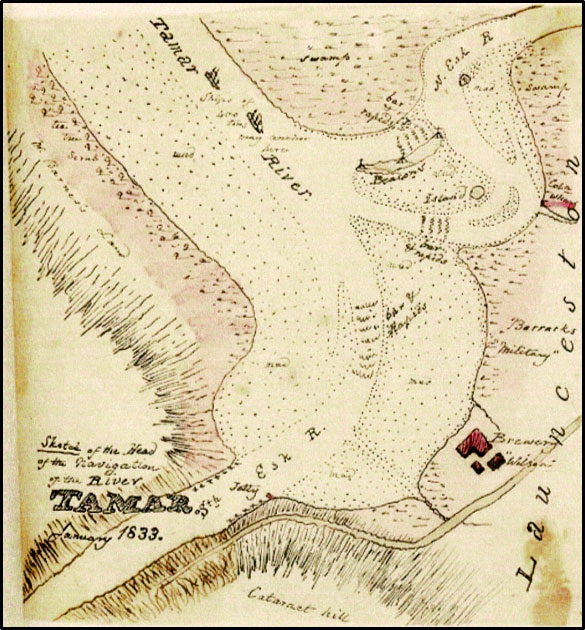

Thomas Scott: Sketches/ Van Diemen’s Land. Sketch of the Head of the Navigation of the River Tamar, 1833; full title shown, bottom left-hand corner. Was drawn 27 years after Launceston was settled. http://image.sl.nsw.gov.au/cgi-bin/ebindshow.pl?doc=pxb216/a557;seq=69

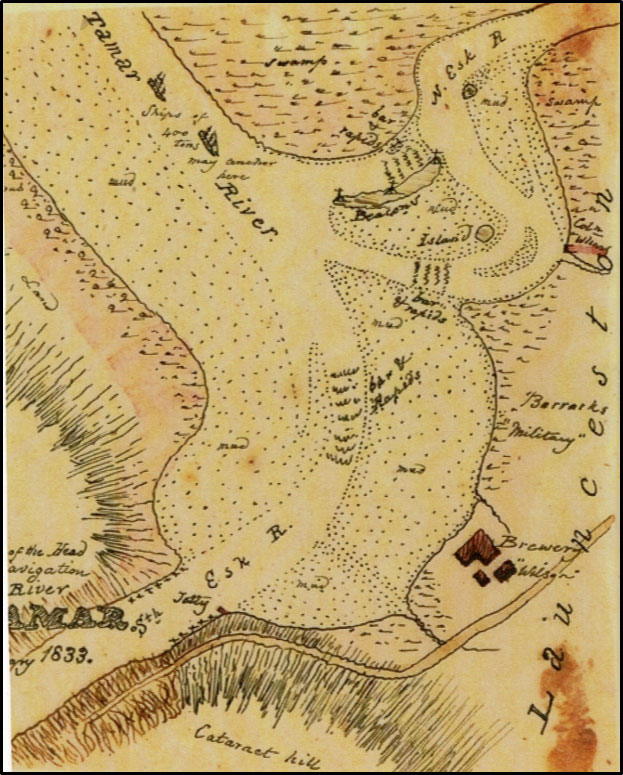

Is an enhanced version showing the written detail more clearly. Enhanced view of the Thomas Scott sketch of the Head of the Tamar River, 1833.

Read More Understanding how First People’s viewed their world

An Encyclopedia of Tasmanian Aboriginal Anthropology

On the 18th February 1802 the Botanist, Leschenault, of the French exploration expedition led by Nicholas Baudin while at Maria Island, came across a small mound with a tent like “wigwam” of bark over it.

An Encounter with the First People of Northern Van Diemen’s Land

Dutch, French, and British explorers set foot in Van Diemen’s Land from 1642 bringing with them a range of preconceptions and prejudices about what and who they might find.

FOOD FORAGING (PART 2 “FORAGING & FOOD PREPARATION”)

Hunting by men was often one of a fortuitous meeting a quarry and resulted in a lack of success having to return to camp empty handed, but not to worry, the ever-reliable women filled the void with smaller fauna, possum and edible flora.

FOOD FORAGING (PART 1 FOOD RESOURCES 2,000 > BP)

The Tasmanian Aborigines occupied their island home for at least 40,000 years but it is only the last 2,000 years that is considered here and only mainland Tasmania and offshore islands.

An Encounter with the First People of Northern Van Diemen’s Land A Particularistic Mindset

When Lieutenant-Colonel William Paterson brought a group of white settlers – soldiers, convicts, and farmers – to Port Dalrymple, Van Diemen’s Land, the English were in a mindset of domination or mastery over other races.

Britain was the world’s naval power, the coming industrial power, the greatest empire builders and affectionately described amongst themselves as the chosen people and the Protestant Protectors.

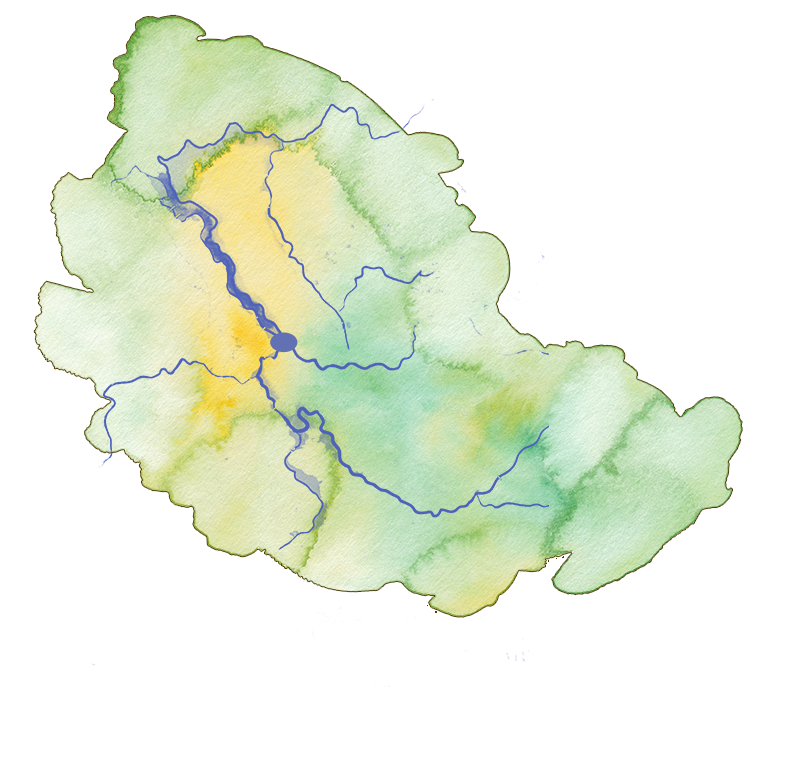

Tamar Valley Geology Determining the First Peoples Occupation of Northern Van Diemen’s Land

When William Collins sailed down the waterway now known as the Tamar, but which he called the Main Head in January 1804, he eventually reached and entered an Arm to the East, the North Esk, and wrote in his logbook1 that “the water is perfectly fresh and good”, it flowed over a flood plain and “the Soil on its banks is very good and there is a great extent of it.”

An Encounter with the First People of Northern Van Diemen’s Land

When William Collins sailed down the waterway now known as the Tamar, in January 1804, he eventually reached and entered a river to the East, the North Esk, and wrote in his logbook.

Adequacy

It is tempting to apply modern terms like ‘sustainability’ to Indigenous practice however the key to understanding First People’s attachment to country is adequacy.

First Peoples did not expend energy on wasted accumulation but on a vast Estate that provided the needs of a robust population using minimal exertion. “It depended on preferring to reduce rather than increase material wants.”

A “grounded” rather than “portable” faith – A Psychic Invasion.

Europeans have always had difficulty in grasping a concept of religion in Indigenous practice and even denied until the mid 20th century that you could apply the term ‘religion’ to Aboriginal practice – magic and sorcery but not ‘religion’.

Tamar Valley Geology determining occupation

When William Collins sailed down the waterway now known as the Tamar, in January 1804, he eventually reached and entered a river to the East, the North Esk, and wrote in his logbook.